National security law is ‘game changer’ for multinationals in Hong Kong

Human Rights Outlook 2020

by Hugo Brennan,

Beijing is determined to curb the political freedoms and civil rights that differentiate Hong Kong from mainland China and the implications for businesses operating there will be far-reaching.

The draconian national security law, imposed on Hong Kong by China at the end of June, contains deliberately vague definitions of secession, subversion, terrorist activities and collusion with foreign powers. It gives Beijing sweeping powers to crush dissent and signals that the global financial hub is likely to become more like Shanghai, Shenzhen or, in the worst case, Urumqi from a human rights perspective.

Investor confidence in Hong Kong is already starting to wane, but how stringently the new law is enforced will determine how multinationals view their future in the city.

Register now for our webinar where we discuss this insight in further depth

Hong Kong on path of convergence with China

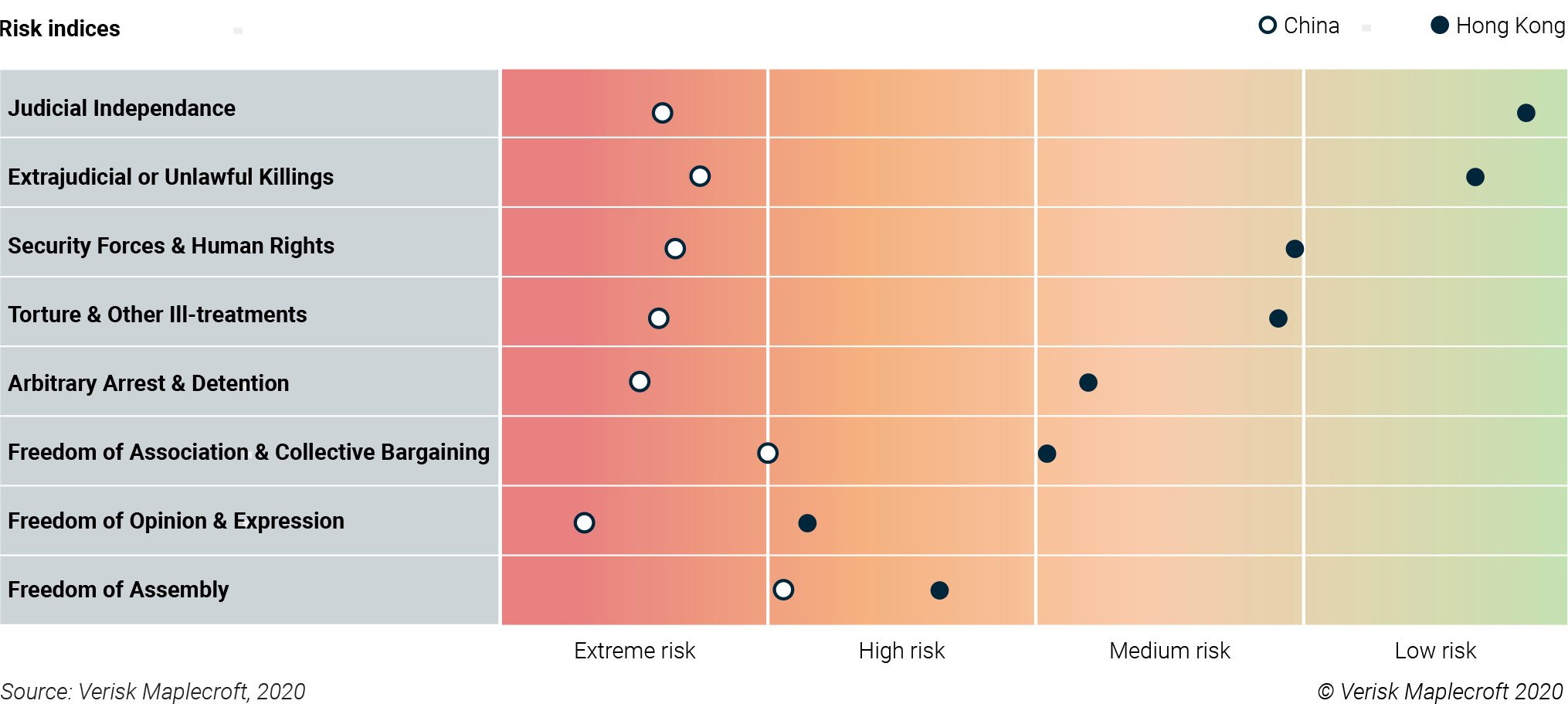

Beijing has been steadily eroding the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ framework that is supposed to guarantee Hong Kong a high degree of autonomy until 2047, but the territory still comfortably outperforms mainland China across the board in our Human Rights Risk Indices (see Figure 1).

However, the National Security Law – and the free hand that it grants Beijing to impose its authoritarian will – means we expect the gulf between Hong Kong and Mainland China’s human rights landscape to narrow over the next decade. The Trump administration’s decision to end US preferential treatment for Hong Kong following the passage of the law demonstrates Washington’s anticipation of this convergence.

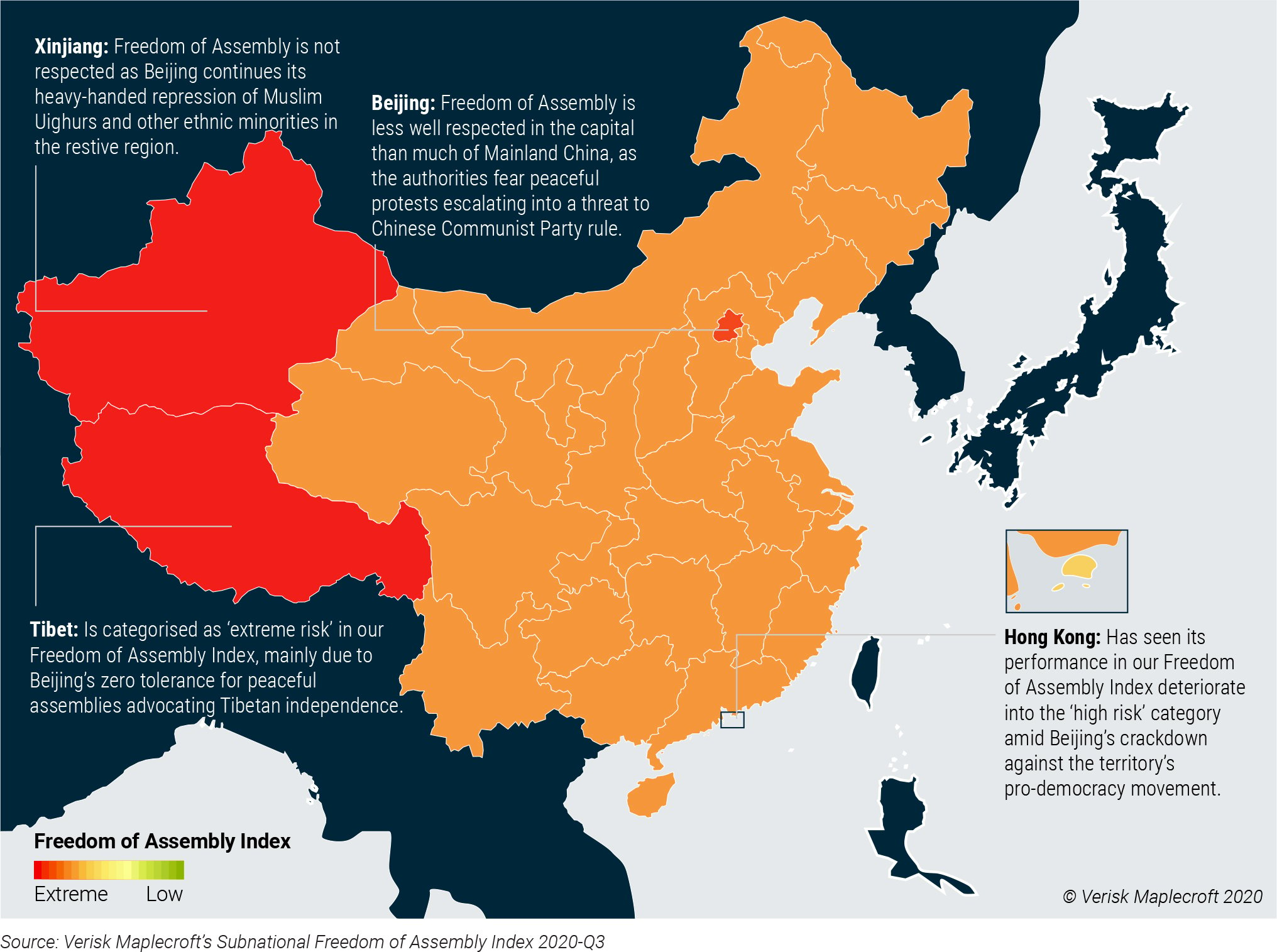

A worst-case scenario would see respect for human rights in Hong Kong deteriorate to the extent that the city becomes reminiscent of other ‘autonomous’ regions of mainland China that chafe under Beijing’s heavy-handed rule, such as Xinjiang and Tibet. Both restive regions are classified as ‘extreme risk’ in our subnational Freedom of Assembly Index, which captures the risk to business associated with violations of the right to peaceful assembly (see Map 1). At the national level, China is ranked 27th highest risk globally in the index.

Hong Kong is currently categorised as ‘high risk’ in the index and ranks as the 78th worst performer out of 198 territories. This represents a notable deterioration from 2019-Q1 – before last year’s crackdown against the pro-democracy movement – when the city was categorised as ‘medium risk’ and ranked 99th. The decision to postpone legislative elections originally slated for September 2020 by a year on the pretext of containing COVID-19 underscores the Chinese leadership’s diminishing appetite to tolerate dissent in Hong Kong and represents another milestone in the city’s deteriorating ESG trajectory.

The challenges for businesses

The new law creates three key risks that multinationals will be particularly exposed to.

1. Politicised detentions linked to geopolitical dynamics

Hong Kong is categorised as ‘medium risk’ in our Arbitrary Arrest and Detention Index in 2020-Q3, a performance that sees the territory nestled between Japan and Montenegro. However, companies need to be cognisant of the increased risk of arbitrary arrest, detention and possible extradition to the mainland that their staff now face under the new law.

Beijing’s record of detaining individuals in retaliation for the actions of their home government should be a major source of concern. Canada, Australia and the US – Western countries experiencing deteriorating diplomatic relations with Beijing – have all warned their citizens that they may be targeted. An extraterritoriality clause means that individuals simply transiting through Hong Kong are also at risk of being arrested for perceived breaches of the law abroad.

2. US-China sanctions crossfire

The national security law has propelled Hong Kong into the front line of increasing US-China strategic competition, and businesses risk getting caught in the crossfire.

On the one hand, companies (and their investors) associated with Beijing’s use of the law to undermine Hong Kong’s autonomy and violate human rights are likely to face US sanctions. The growing list of firms on America’s blacklist because of links to Beijing’s mass incarceration of Muslim Uighur’s in Xinjiang provides a signpost for things to come.

On the other, multinational companies with a footprint in Hong Kong that comply with US sanctions levied against China – including for example, export restrictions against Huawei – are in danger of being accused by Beijing of colluding with foreign powers. We expect this crossfire to intensify as US-China relations continue to deteriorate over the coming decade.

3. Toe the line or else

Under the new law, companies face fines, asset seizures or the revocation of their business licence if judged to have threatened national security. The fact that such cases will be adjudicated by government-appointed judges – or worse still, be tried on the mainland – suggests that Hong Kong’s ‘low risk’ categorisation in our Judicial Independence Index is under severe threat.

The national security law is designed to ensure that global firms toe Beijing’s political line or risk exposing their Hong Kong operations and employees to criminal charges. The sweeping and vaguely defined provisions of the law mean that it isn’t clear where the line will be. For example, previous instances of corporate blunders around the controversial status of self-governing Taiwan could – in theory – now result in firms finding themselves in court for promoting secession.

Download the full report

Human Rights Outlook 2020Hong Kong will no longer be a bastion of freedom

We expect Hong Kong’s performance in our human rights risk indices to deteriorate over the coming years, as Beijing uses the national security law as a tool to continue to tighten its grip over the territory. The pace of decline will be heavily influenced by how the law is applied and enforced in practice.

Businesses need to understand that the national security law is a game changer for Hong Kong. Foreign residents and visitors are now within reach of the long and politicised arm of Chinese law. The expected erosion of human rights under the auspices of the law will increase the risk of being caught in the US-China sanctions crossfire. And multinationals now have little choice to toe Beijing political line or face the legal consequences.