Renewable energy is the ‘green’ panacea to the carbon-tinged reputation of fossil fuels, set to lead efforts to temper climate change and expand access to electricity. But as the third energy transition gathers pace, a deeper examination of the industry’s supply chains and operational practices reveals a darker side when it comes to human rights.

Some of these challenges, such as those around the cobalt used in lithium-ion batteries, are well-known. However, while the persistent presence of child labour in Congolese cobalt mines has left companies struggling to address supply chain traceability, other human rights impacts from renewable energy may be flying under the radar.

Our research shows that labour rights issues are present in renewable energy supply chains, including in the manufacturing of solar panels and the cultivation of palm oil and sugarcane used in biofuels. Looking further down the value chain, the rights of vulnerable communities can also be put at risk by major renewables projects developed on their land.

So, while one side of the green revolution offers critical sustainability benefits, the image and reputation of energy operators, investors and end-users can also be highly exposed to human rights issues that could cast a shadow over the sector’s socially responsible credentials.

Land rights and supply chain traceability among key challenges

In theory, the renewable energy industry is in a strong position to address this. Given its de facto status as a sustainable industry, shareholders are more likely to demand transparency and accountability beyond that mandated by laws such as the UK Modern Slavery Act. As funding mechanisms, including green bonds, also increase in popularity, their requirements for socially responsible projects can drive best practice efforts to reduce human rights violations within the sector. But in reality, this will remain challenging.

Download the webinar recording: Why is the environment the hottest human rights issue?

A case in point is a recent industry report from the non-profit organisation the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre that found almost half of all renewables companies surveyed did not have any human rights policies in place.

With expansion moving forward in both developed and developing countries, addressing land rights governance and supply chain traceability is easier said than done. Identifying a clear picture of the human rights risks associated with renewable energy production will remain a necessary step towards achieving truly sustainable energy processes.

Watch out for solar energy’s risk hotspots

With a history of excessive working hours and occupational health and safety (OHS) violations in the manufacturing sector, China’s position as the leading producer of solar panels globally should prompt focused supply chain due diligence in the sector. Although China has made significant improvements in environmental standards attached to photovoltaic cell manufacturing, OHS issues in its solar industry are not uncommon.

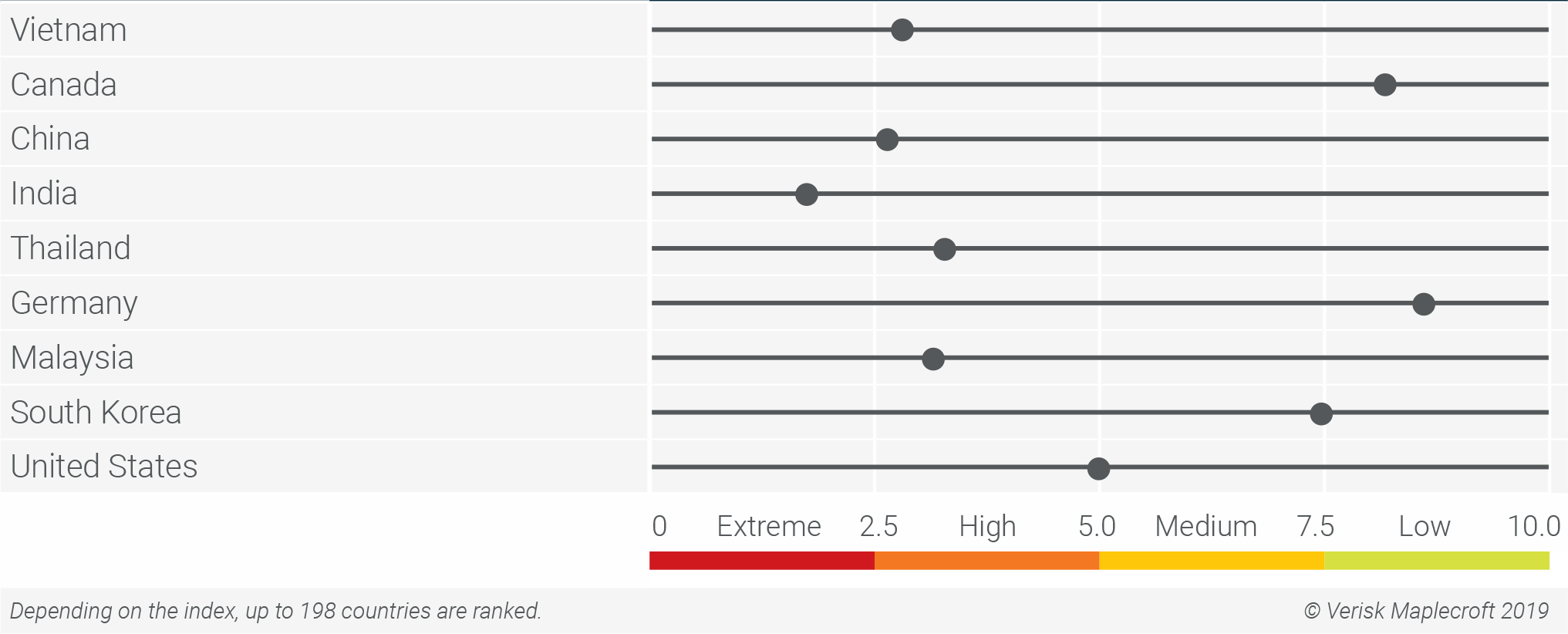

Workers’ exposure to hazardous chemicals, such as cadmium, in the manufacturing of PV panels is particularly concerning given weak and inconsistent enforcement of OHS standards in China. While direct evidence of such issues in other major solar panel-producing nations is slim on the ground, our OHS Index scores indicate some of these demonstrate a similarly risky operating environment (see figure 1).

Further human rights risks may be looming if upstream inputs become a focal point. Industry supply chains for quartz, the raw material from which polysilicon for photovoltaic cells is produced, are somewhat opaque, posing a challenge for those seeking to understand upstream risks. Demand for solar panels is also driving exploration for high purity quartz deposits, including in countries where labour standards are poorly enforced, such as Mauritania and Saudi Arabia.

The inherently hazardous nature of mining in poorly regulated countries, combined with quartz mining’s links with the respiratory disease silicosis, significantly raises the potential for labour rights violations to occur.

Palm oil and sugarcane fuelling feedstock risks

While the biofuels industry has faced criticisms ranging from driving deforestation and land grabs to causing food insecurity, its links with labour rights issues often don’t get as much attention.

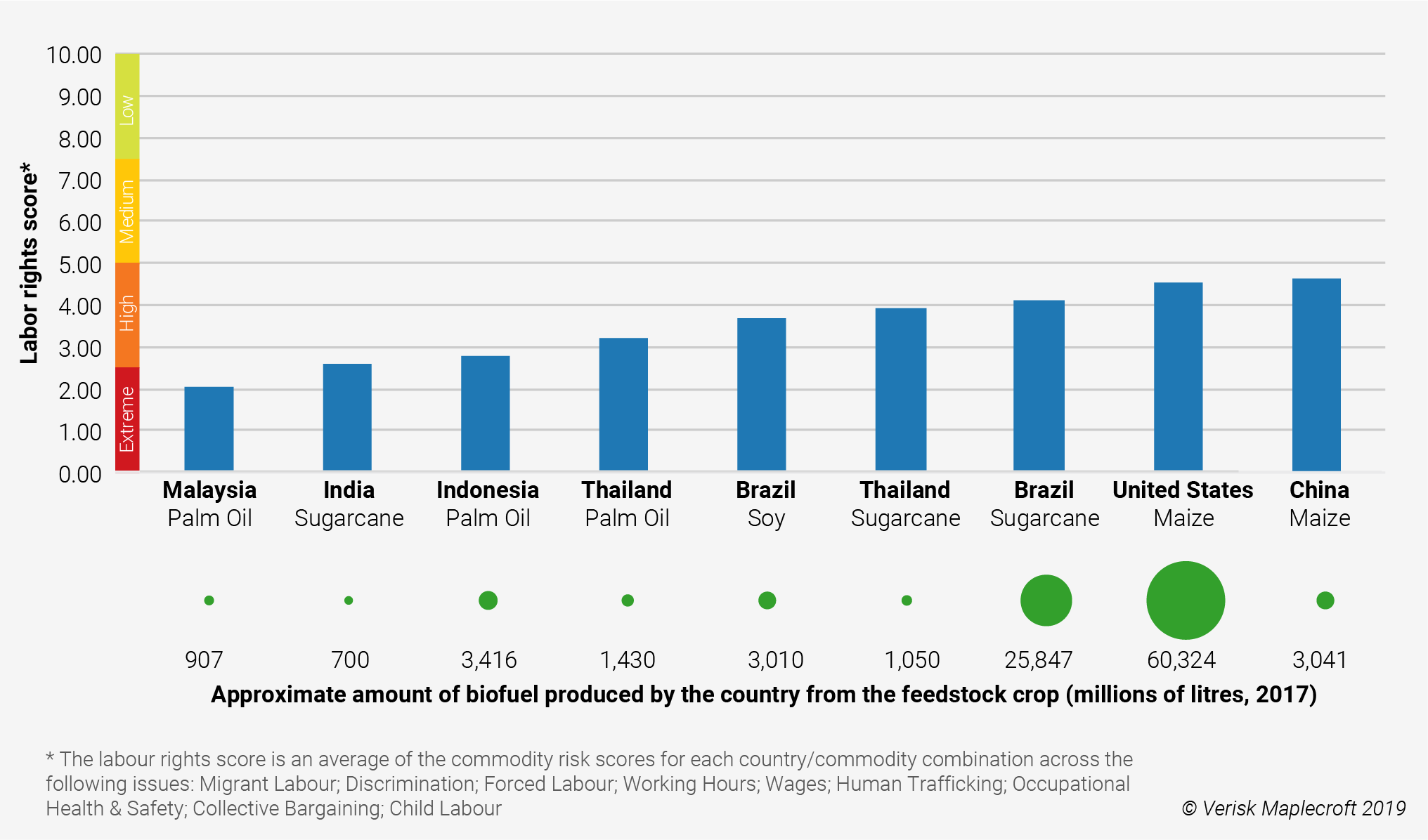

Across a selection of major producing countries for key crops used in the production of biofuels, our commodity risk data shows that overall labour rights scores are worst for the cultivation of palm oil in Malaysia and Indonesia, along with sugarcane in India. Palm oil in Thailand and soy in Brazil follow close behind (see figure 2).

The widespread use of migrant labour in India’s sugarcane industry and in the palm oil industries in Malaysia and Indonesia also increases the risk of modern slavery occurring. Child labour has also been found in the production of these crops in all three countries. Inadequate enforcement, corruption and a lack of political will to address these issues are key challenges facing these producing economies in tackling violations.

Wind farms in Mexico propel indigenous land rights violations

Outside of labour rights issues, companies involved in land-intensive renewable energy projects, such as wind and solar farms, face exposure to risks of association with land rights violations that can create delays and disruption.

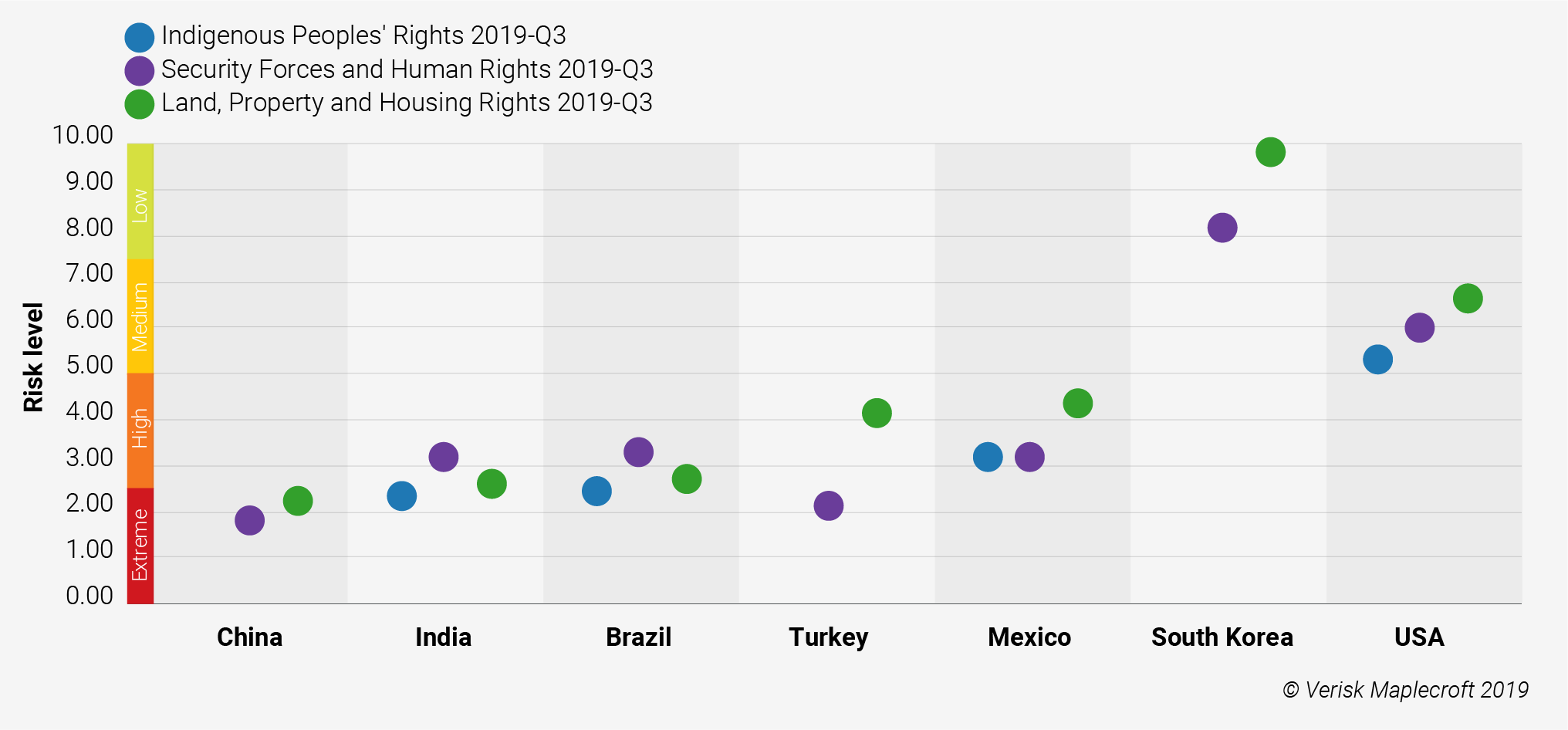

China, India, Brazil, Turkey, Mexico, South Korea and USA are amongst the countries where significant expansion of the wind sector is expected in the next decade or so. As figure 3 shows, five out of these seven countries are assessed as ‘high’ or ‘extreme risk’ in our indices covering indigenous peoples’ rights, land rights; and security force violations.

Major projects in countries such as Kenya, Taiwan and Morocco have all been subject to scrutiny over these issues, but Mexico is the prime example of where we’ve seen these risks collide with negative impacts for operators and investors.

The state of Oaxaca is home to at least 28 wind farm megaprojects, many of which have been contentious due to their association with indigenous land rights violations, forced displacement, inadequate consultation and violations by security forces. Due to intense opposition by local communities, wind farms have faced lawsuits and operational delays, posing significant financial risk to investors. Protestors have faced intimidation, death threats and violence by Mexican security forces, exposing the country’s wind energy sector to heightened reputational risks.

Securing social licence to operate holds key to project success

Major community resistance against wind farms, and indeed other solar and hydropower projects, have resulted in significant financial costs to renewable sector investors. The cancellation of a 61MW wind farm in Kenya in February 2016, due to widespread community opposition, included a court case over the project location and resulted in a shareholder investment loss of USD66 million.

A failure to respect land and indigenous rights will result in prolonged community distrust towards renewable energy operators. While challenges in obtaining free, prior and informed consent – the backbone of securing social licence to operate – are significant, success stories have been recorded in ‘high risk’ countries such as Mexico. Despite difficulties, Oaxaca has also produced renewable energy projects that empower local communities, such as the Ixtepec wind project. Building on models such as this could form a roadmap for investors to reduce reputational and operational risks and benefit local populations.