Five major obstacles to a US-Iran deal

by Torbjorn Soltvedt,

US President Joe Biden and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani have both expressed their support for reviving the 2015 nuclear agreement (JCPOA). But finding a practical solution that would see the US re-join the JCPOA and Iran return to compliance will be far from straightforward.

Our base case is that the US remains outside the JCPOA during the first half of 2021. With Iran’s presidential election just four months away, an agreement before then is unlikely. The outlook for the second half of the year and beyond is highly dependent on the outcome of the vote and working out a solution will remain an uphill battle. In this analysis, we highlight five of the most important obstacles.

1. Iran's election cycle and growing influence of hard-liners

The domestic political conditions for an accord are worse than when the original deal was struck in 2015. Two years before the conclusion of the JCPOA, Hassan Rouhani had been elected on a platform of resolving the nuclear issue and using an agreement as a vehicle for opening and accelerating the Iranian economy.

Find out more about our Country Risk Intelligence

The failure of the JCPOA to deliver a clear economic dividend has unsurprisingly strengthened hard-line factions that were sceptical of the deal in the first place. The parliamentary election in February 2019 effectively reversed the swing towards Rouhani’s centrist camp four years earlier. With centrists weakened, and reformists barred from the political process, anything other than a victory for a hard-line candidate in June’s presidential election would be a surprise.

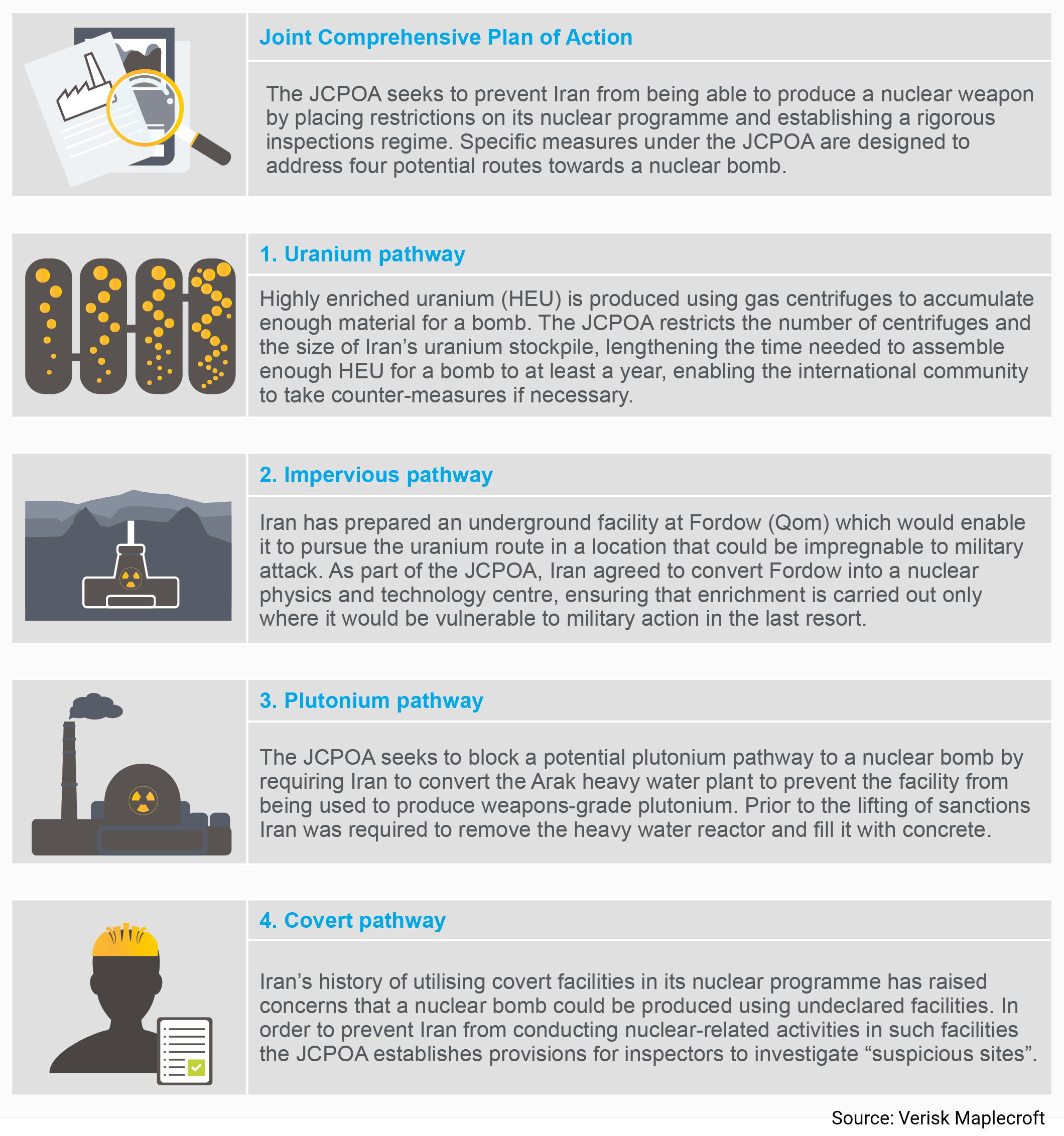

The growing influence of hard-liners has been evident in Iran’s nuclear posture over the last year. After gradually reducing its compliance with the JCPOA since mid-2019, Iran’s breaches of the agreement have become more serious in 2021. Most notably, Iran has increased uranium enrichment to 20% at the underground Fordow facility and is spinning more advanced centrifuges at Natanz. While such steps form part of broader efforts to negotiate from a position of strength, an extended period of serious Iranian non-compliance could ultimately kill the JCPOA.

2. Lack of US Congressional support

The Biden administration will have to carefully weigh how much political capital to spend on pursuing an agreement that is highly controversial in the US Congress.

Iran and the JCPOA were conspicuous by their absence in Biden’s initial foreign policy address on 4 February 2021. Although Biden is laying the groundwork for a possible US return to the JCPOA, he has yet to put much weight behind the initiative.

Biden will be acutely aware of how much the Obama administration relied on executive orders and other workarounds to overcome strong bipartisan opposition to the JCPOA in Congress. Given the tight margins in the Senate, Biden will have little choice but to go down the same route as Obama in order to secure a deal. But after the experience of the last five years, Iran will be wary of another agreement that ultimately relies on the support of the US president to function as intended.

Learn more about our work in the oil & gas sector

3. Trump-era sanctions

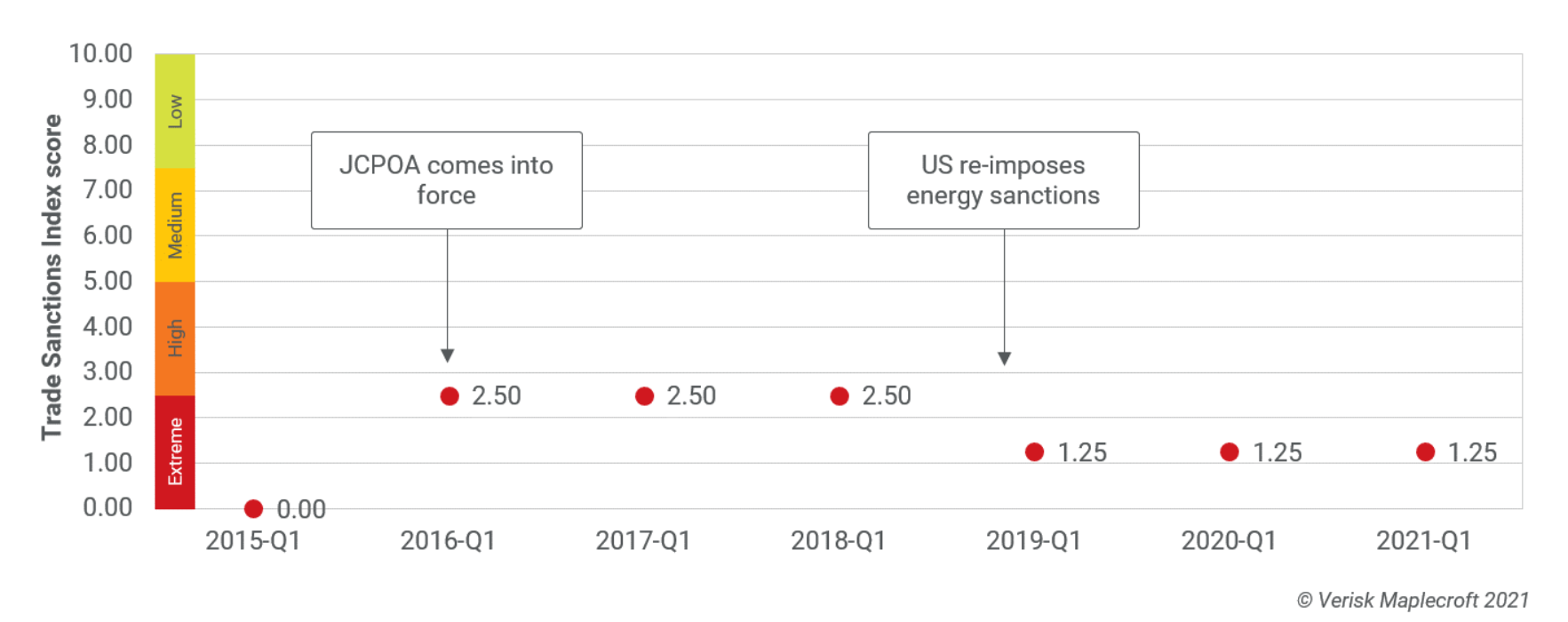

Biden’s task of disentangling a broad range of longstanding US sanctions against Iran is made more difficult by the significant expansion of sanctions under the Trump administration. The web of US sanctions on Iran is now even more complex than when the JCPOA was concluded in 2015. When the deal came into force in 2016, the number of blacklisted Iranian entities subject to US secondary sanctions stood at 175. After the Trump administration’s ‘maximum pressure’ campaign, the number has reached 944.

Most importantly, the blacklisting of all the main actors in Iran’s energy sector under global terrorism sanctions lists in October 2020 has disconnected sanctions on Iran’s oil sector from the framework of the JCPOA. Even if Biden concludes that Iran is in full compliance with the JCPOA, he will still have to make the case that revenue from Iran’s oil sector is not used to fund the activities of the Revolutionary Guard in order to lift the terrorism-related sanctions on Iran’s oil & gas sector. Although this is an additional step Biden could take, it would raise the political capital needed to push a deal through. For Iran, a US return to the JCPOA where extensive non-nuclear-related sanctions on its O&G sector remain in place would be of little value.

4. Opposition from Israel, Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Israel, Saudi Arabia and the UAE all criticised what they saw as a lack of consultation by the Obama administration before the conclusion of the JCPOA in 2015. Biden has hinted that he would take a more consultative approach. But Israeli, Emirati and Saudi expectations of a more comprehensive agreement that would also cover Iran’s regional posture present Biden with a dilemma: incorporating non-nuclear issues such as Iran’s ballistic missile programme would make a new nuclear deal much more difficult to achieve. But leaving them out would risk damaging relations with key regional allies.

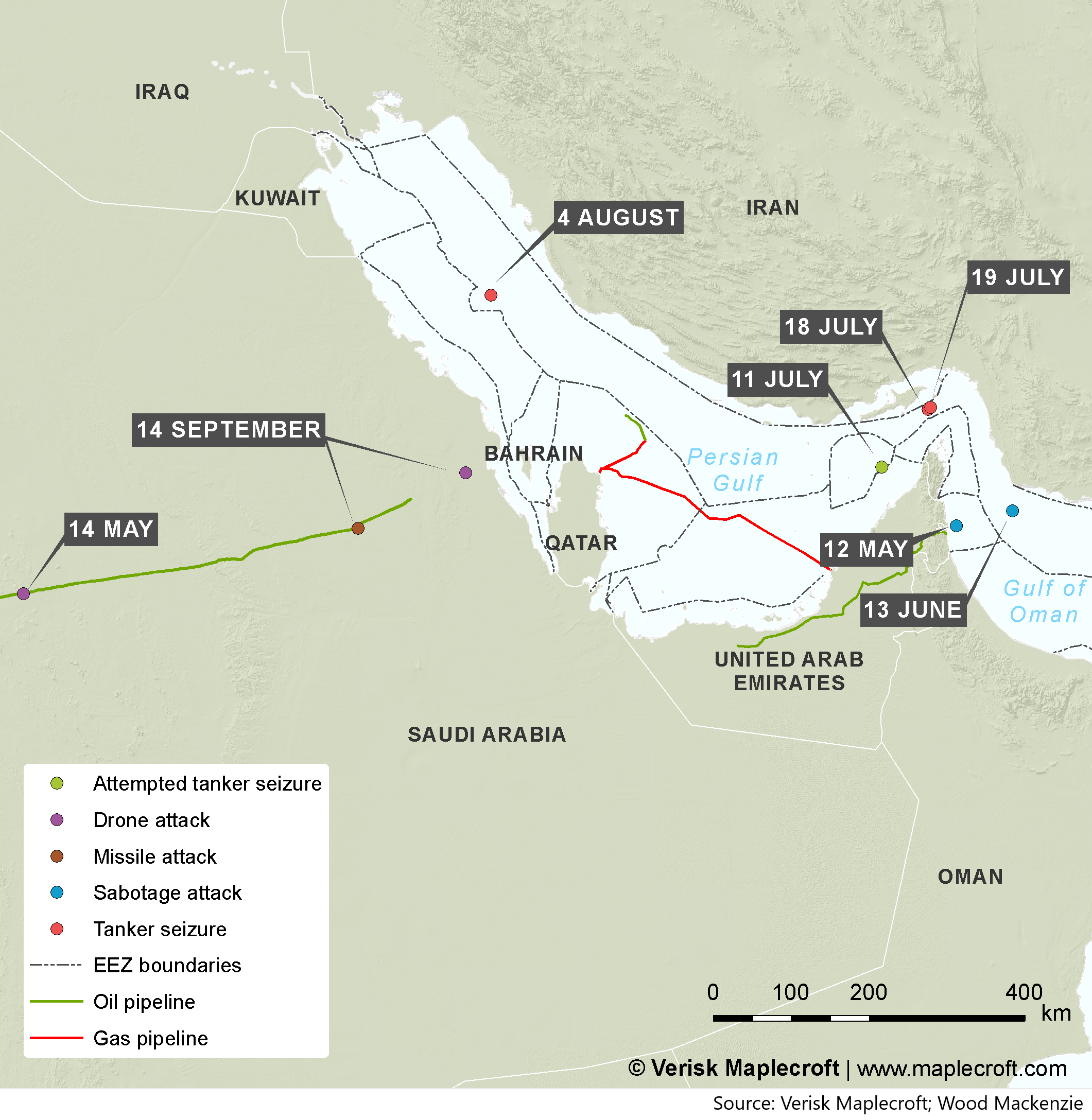

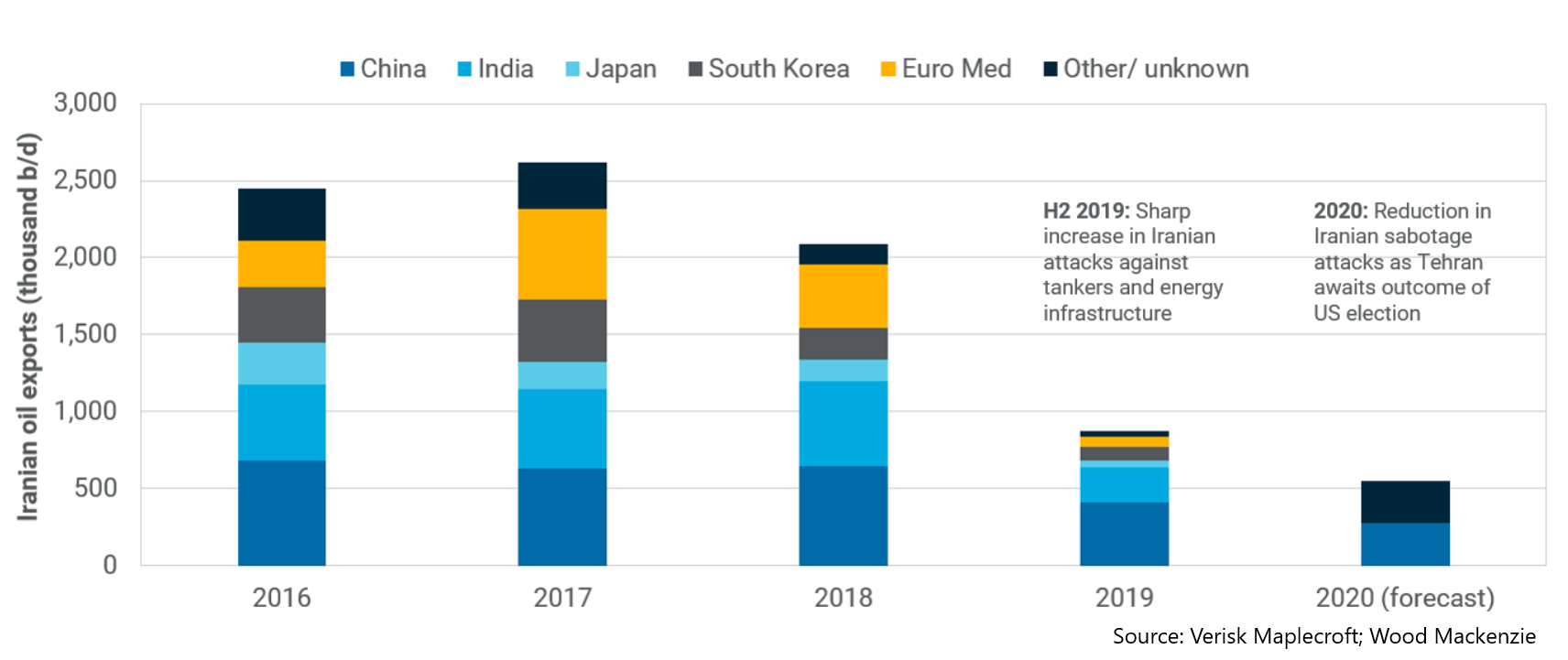

An easing of tensions would be in the interest of all Persian Gulf exporters. Most of the Middle East’s main oil producers have benefitted from the Trump administration’s 'maximum pressure' campaign against Iran. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, in particular, have been well-placed to replace Iranian barrels taken off the market by US energy sanctions.

Events during the second half of 2019 nonetheless showed that there is a downside: heightened regional tensions and greater maritime insecurity in the Persian Gulf, Strait of Hormuz and Gulf of Oman. Despite this, a straight US return to the JCPOA without additional Iranian concessions is unlikely to secure the support of Israel, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

5. Mutual distrust

A big part of the challenge will be to translate a mutual willingness to return to the framework of the JCPOA into practical steps toward a resolution. Although the JCPOA provides a blueprint for this process, mutual distrust will make it more difficult than in 2016 to synchronise sanctions easing and a reduction in Iranian nuclear activities.

After the JCPOA’s ‘Adoption Day’ on 18 October 2015, the lifting of international and US-nuclear related sanctions began three months later, after the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) had verified Iranian compliance with the agreement.

Now, Iran is calling on the US to return to the JCPOA and lift sanctions before it brings its nuclear activities back in line with the parameters of the JCPOA.

Unless either side moves first, the only way around this impasse will be a more gradual process where both sides make incremental changes near simultaneously. As an example, the Biden administration could offer limited sanctions waivers to allow a managed and gradual increase in Iranian oil exports in return for a reduction in nuclear activities. Trust will be the main obstacle, and Biden and Rouhani would both have to withstand pressure from domestic sceptics and critics pursuing a maximalist position.

Outlook

The next four months will offer several signposts for the trajectory of US-Iran relations and the prospects of a US return to the JCPOA.

First, Iran has threatened to expel IAEA inspectors if US nuclear-related sanctions are not lifted by 21 February 2021. Any removal of inspectors would make an agreement much more difficult to achieve; without mechanisms for monitoring Iran’s nuclear programme, mistrust from the US and the remaining parties to the JCPOA would deepen.

Iranian oil exports will be another crucial indicator. Volumes are already rising, and the coming weeks and months will give a better indication of how strongly the Biden administration intends to enforce energy sanctions while pursuing a deal in parallel.

Finally, the run-up to June’s presidential election will give a clearer indication of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s willingness to endorse another serious effort to reach an accord with the US on the nuclear issue. An agreement between Iran and the US before then is a remote prospect, and the risk of Khamenei walking away from the JCPOA this year will remain high.