China’s COVID surveillance measures are here to stay

by Sofia Nazalya,

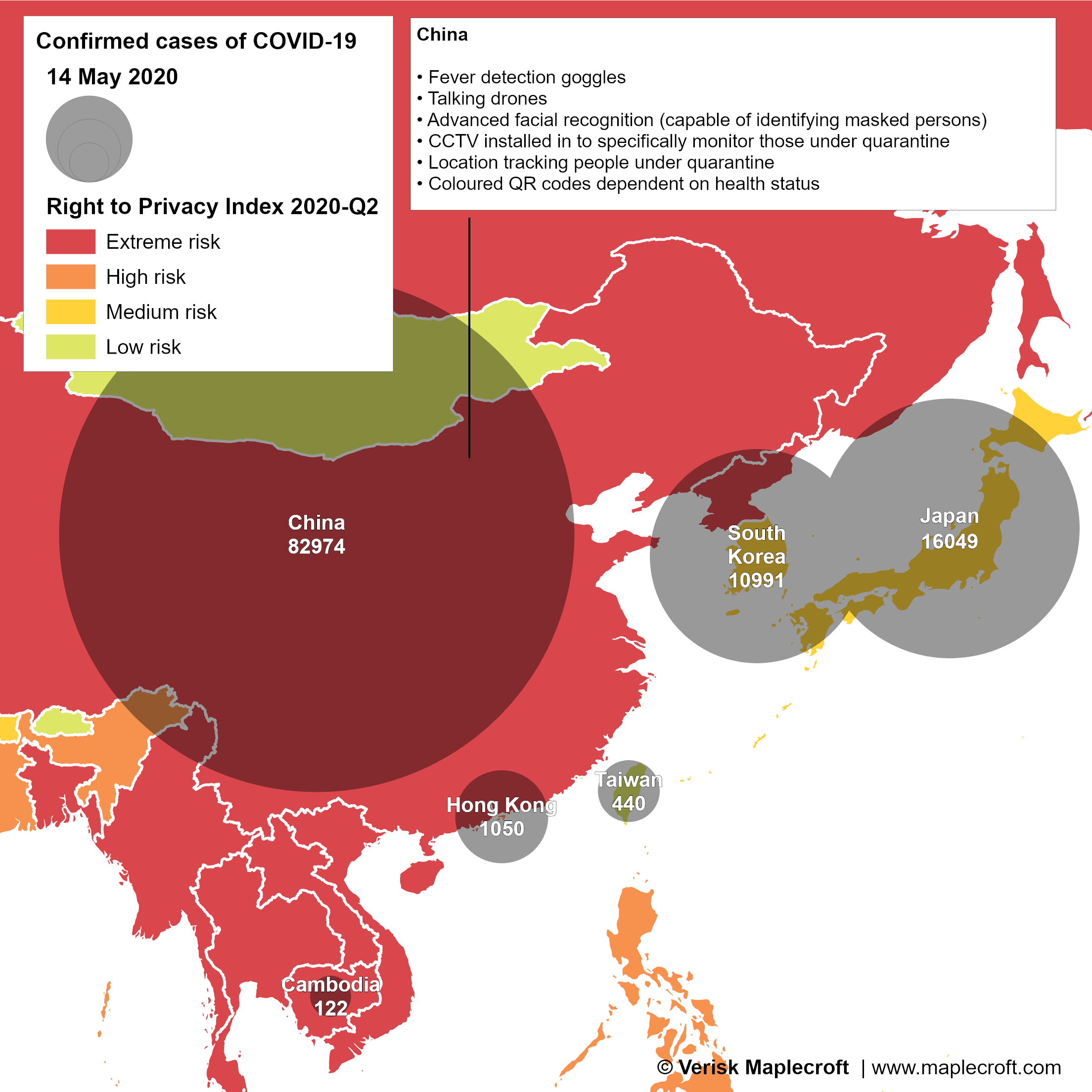

COVID-19 has left the door open for Beijing to ramp up the extensive surveillance of its population by introducing new and extraordinarily invasive methods under the guise of fighting the pandemic. Talking drones now berate individuals for not wearing masks, while CCTV installed outside the homes of those under quarantine watch their every movement.

Measures such as these go beyond even what Chinese citizens are typically used to, but we expect them and others to remain part of China’s post-pandemic ‘new normal’ – with significant implications for the privacy of individuals and businesses alike.

China among world’s highest risk countries for breaches of privacy

We expect Beijing to retain extensive surveillance indefinitely, under the pretext of preventing a resurgence of the coronavirus. This will provide the CCP with even more fine-tuned powers to track, monitor and record private information. While the ability to track and record an individual’s location is not new, measures implemented in the time of the pandemic have given the government an additional layer of surveillance.

China records the 4th worst score in Asia, and 14th worst globally in our Right to Privacy Index. With COVID-19 surveillance measures expected to continue, China is likely to see a further deterioration in its ‘extreme risk’ score.

Given the perceived necessity of such measures during the pandemic, tighter surveillance has not triggered a backlash amongst the Chinese public. Under the circumstances, this is to be expected. However, this also means foreign companies operating in China will be subject to ever more sophisticated and comprehensive data collection and surveillance that will put their operations and employees under the watchful eye of the state.

Lack of transparency in personal data use problematic

But Beijing’s track record of extending surveillance in the name of public health shows that the human rights implications can be severe. We saw this in Xinjiang, where, under the pretext of gathering medical information, Chinese authorities collected biodata, including DNA samples, fingerprints, iris scans and blood types, from residents between the ages of 12 and 65 from some parts of Xinjiang.

The disproportionate collection of medical data – some of which reportedly took place under duress – is particularly problematic considering the human rights violations against Uyghurs that have since taken place. While Chinese data protection laws offer some protections to personal data collected for the prevention and control of epidemic diseases, the Xinjiang example suggests there is little transparency on how personal data will be used by the authorities. The ratcheting up of surveillance will only add to this concern.

Chinese technology will surge ahead, but responsible investors will be wary

With access to extensive consumer data and technical know-how, Chinese tech companies have emerged as important partners in the state’s fight to curb the pandemic. Alibaba, Baidu, ByteDance, Tencent and Xiaomi have all been instrumental in harnessing surveillance methods to track the outbreak. This means they will also play an increasingly crucial role in strengthening the state.

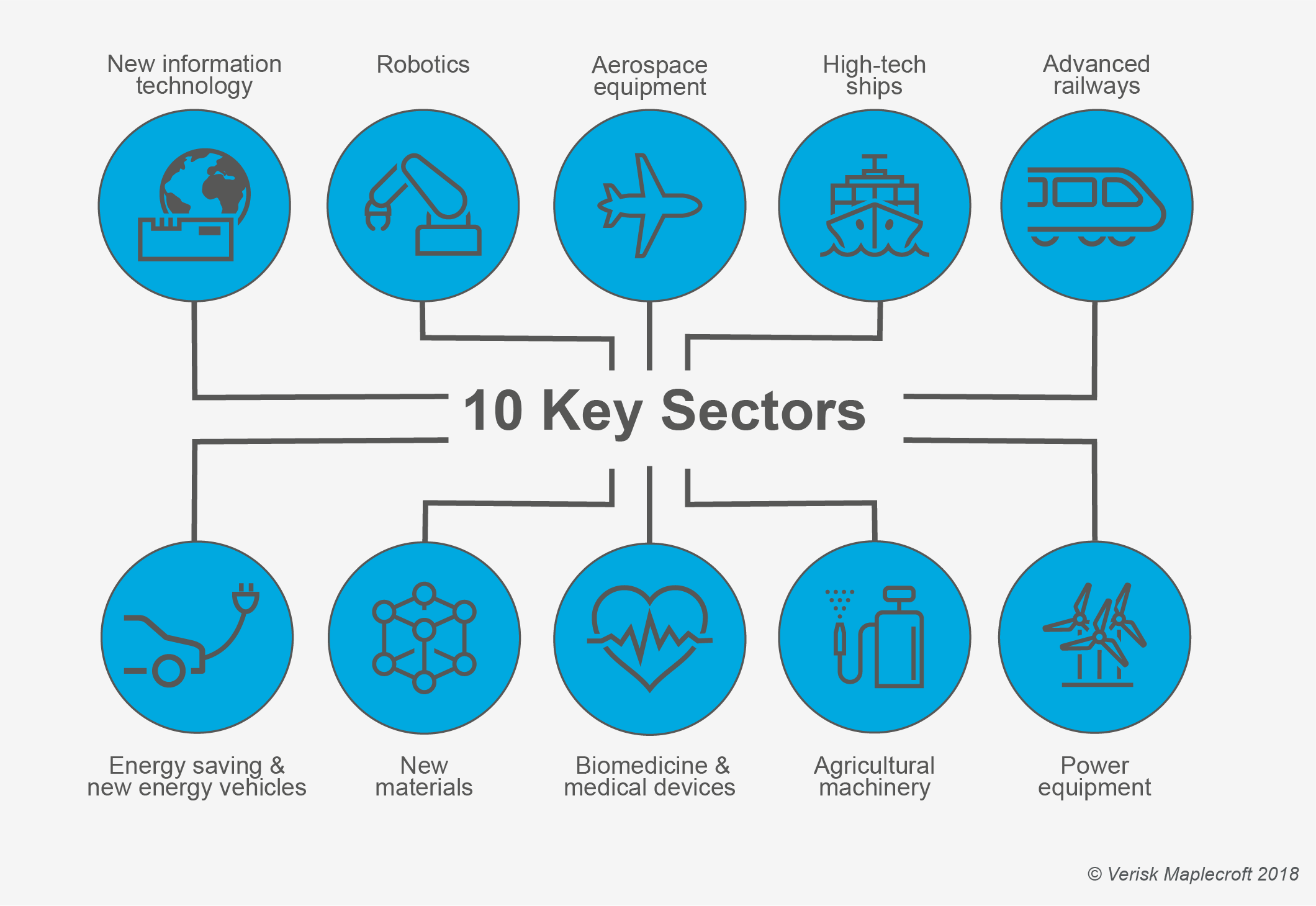

As the country looks to rebuild its economy, it will turn to homegrown innovation in the form of Chinese tech companies. Instead of dampening Xi’s ‘Made in China 2025’ ambitions, which calls for the country to lead in areas such as robotics and new information technology, the pandemic is likely to reinforce this vision (see figure below).

We expect international interest in investing in China’s tech giants and start-ups building these capabilities to grow exponentially in the coming years. However, investing in Chinese tech companies is not without regulatory and reputational risks.

The US blacklisting of several Chinese tech companies – including HikVision, SenseTime and Megvii – due to their links to human rights abuses in Xinjiang illustrates the reputational risks for institutional investors. Crucially, current and emerging legislation that delists or places sanctions or bans on corporates with links to human rights abuses outlines how risky it is to get into bed with tech companies that have become entangled with state surveillance.

Read more on conducting Human rights due diligence

Companies will be under the microscope

But reputational and operational risks are more widespread. All foreign companies in China, regardless of the sector, have little choice but to operate in an environment with limited respect for privacy and transparency on how the state uses collected personal data. As it is, companies must tow the line with Beijing, or ultimately risk losing access to the Chinese market. The ongoing implementation of the controversial Social Credit System (SCS) in particular will have significant implications.

With the threat of the virus resurfacing, companies are at risk of being penalised under the SCS if they do not implement social distancing measures in the workplace. Similarly, if employees are found to be endangering public safety, for example by flouting ongoing travel restrictions or hiding their medical history, they will be at risk of having their social credit score docked. This has direct repercussions for business, given that employees’ misbehaviour and poor social credit record would in turn reduce the corporate credit score of their employers.

While China is keen to claim that an all-encompassing approach to surveillance will be necessary to protect public health, the repercussions on both individuals and corporates will be far reaching. Not only will China’s ‘new normal’ be characterised by further erosion of individual anonymity and privacy, intensified surveillance will see companies under a state operated microscope unlike anything they have experienced before.