Wave of political instability threatens South America’s Pacific coast

by Jimena Blanco and Eileen Gavin,

Thanks to COVID-19, Latin America is on course for a third ‘lost decade’, and 2021 is set to inject a dangerous dose of political instability into the economically fragile region. The pandemic is taking an unprecedented human, economic and political toll, laying bare the region’s decades-old structural deficiencies, which have crippled the effectiveness of government responses to the health crisis.

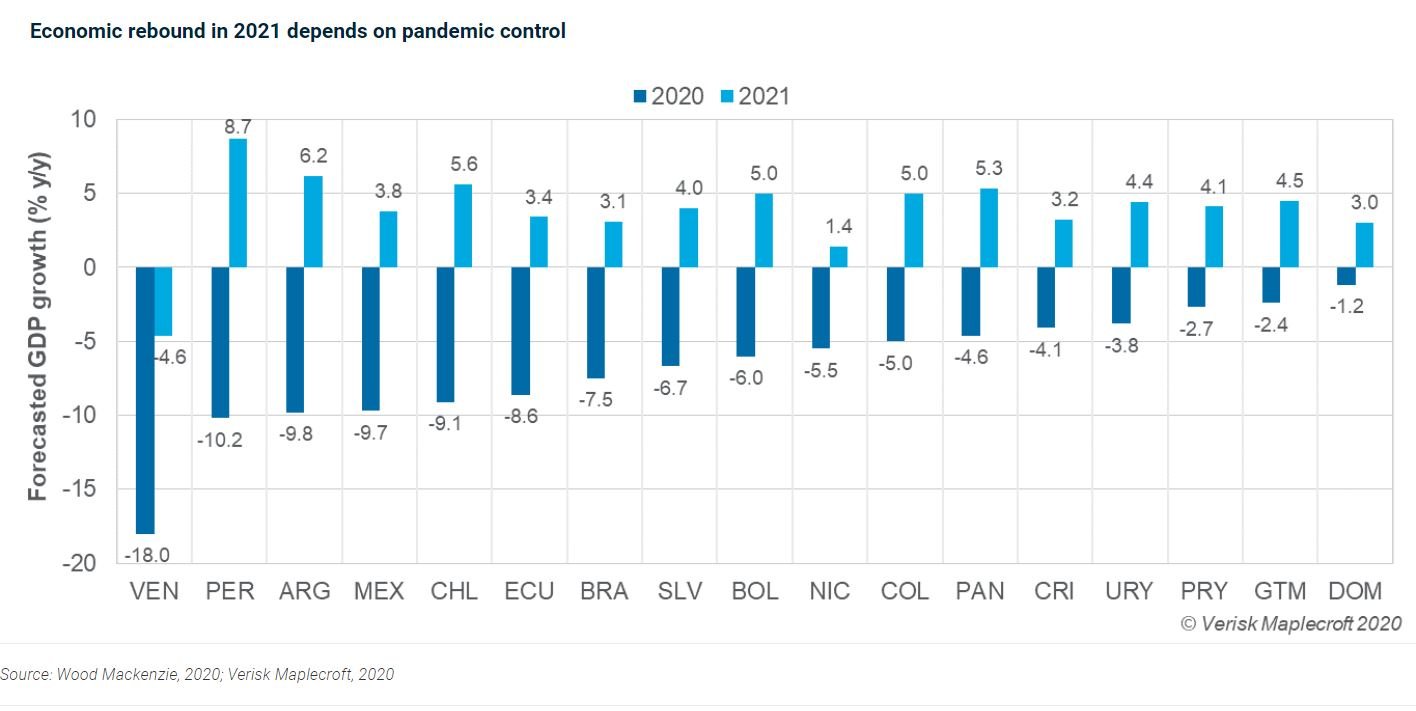

Andean countries on the Pacific coast have been hit hardest. Peru has recorded the highest number of deaths in the world per 1 million population (966.79 as of 16 September); followed closely by Chile (642.85) and Ecuador (641.7). All three head into crucial election cycles with decimated economies and discontented voters (see Figure 1), which is serving to crack open pre-existing fractures in the political landscape, setting the scene for the potential rise of disruptive, anti-establishment, ‘outsider’ candidates.

Learn more about our Country Risk Intelligence

Investors are highly exposed in Chile and Peru, which recorded positive economic growth for much of the past two decades. The pair are the world’s top copper producers, with social and political instability risking disruption to global supply chains. Ecuador is an attractive mining exploration frontier; social and political upheaval would put paid to its goal of catching up to its peers.

The main risk over the coming year is a long-lasting corrosion of political stability. Governments from Santiago to Quito are on the back foot, as the pandemic continues to erode public support for high profile presidents. This, in turn, is emboldening challenges to these executives by other institutions – particularly the legislative branch – and driving up the risk of social unrest.

A shorter social fuse and elections make for a volatile cocktail in the Andes

Ecuador and Chile already saw large outbreaks of social unrest in late 2019 and early 2020 that threatened to topple the two governments, while in Peru protests were also ticking up well before the pandemic hit, reflecting heavy public disillusionment with elected officials embroiled in serious corruption scandals. Reflecting several years of social discontent and political upheaval, Peru and Chile latterly have seen the most unstable cabinets in a generation, with ministerial revolving doors all but eliminating the effective implementation of government policies.

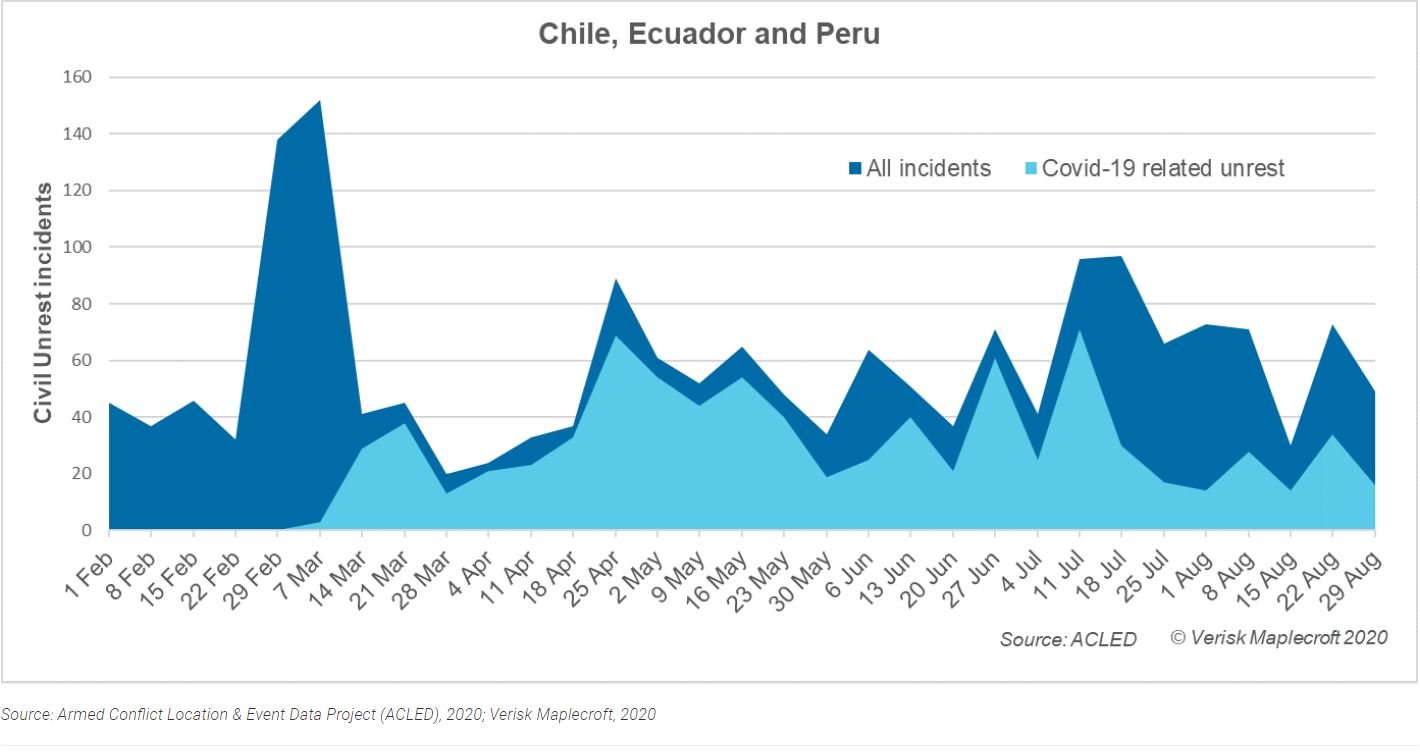

At the outset of the pandemic in March, the COVID-19 lockdowns effectively put a the lid back on these simmering social and political tensions. However, data compiled by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) shows that civil unrest incident numbers were back pre-pandemic levels by May. With public discontent extending well beyond the pandemic, regional voters will be in a punishing mood in 2021 and wanting change – potentially making them more receptive to grand populist pledges.

Public discontent is not only undermining the traditional ‘incumbent advantage,’ it is also encouraging intense congressional political jockeying for position in advance of 2021 elections. This has further crippled policy implementation. Fragmenting legislatures in Chile and Peru have weakened governance – which we expect to remain the case after next year’s general elections.

Stability on the slide

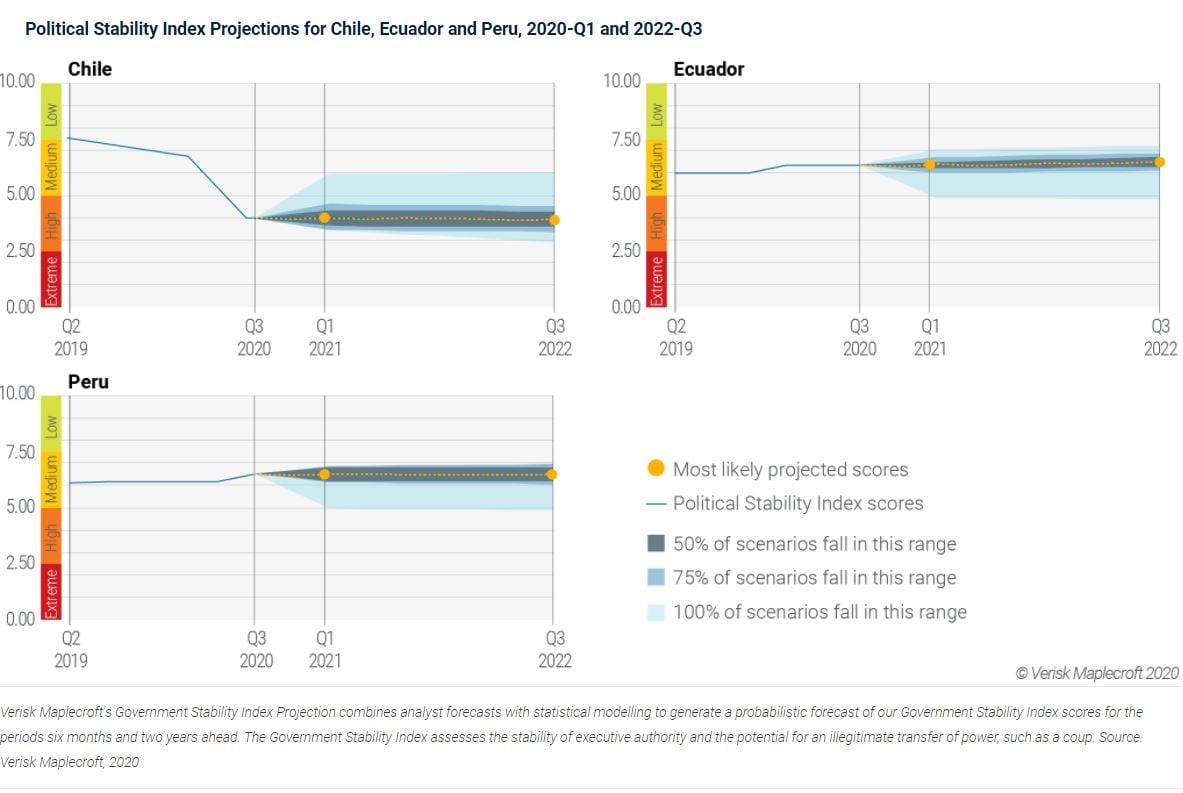

Our Political Stability Index Projections see the greatest risk of a deterioration in Peru, with a strong 74.5% probability of the country’s score worsening over the coming two years (see Figure 3). Peru’s fragmented political scene and the collapse of traditional national parties under the weight of corruption scandals means the 2021 race is wide-open and very unpredictable. Two thirds of voters are apathetic towards all the prospective candidates, leaving a national football-star, turned municipal mayor, as the current front-runner.

Peru’s glut of small populist regional parties will look to take advantage of the economic crisis and leverage social discontent to gain a solid footing. And while Peruvians traditionally place very high value on macroeconomic stability at the ballot box, the 2021 presidential contest could propel an untested radical newcomer – rather than the typical moderate – over the line.

In Ecuador, the outlook is only marginally better, and political stability will be on a knife edge over the next two years. The exclusion of former president Rafael Correa from the February 2021 race risks increasing the political temperature between the radical left and the traditional right wing, which is determined to get back into office after 15 years in opposition.

Although he failed to secure a ballot slot, Correa’s proxy candidate, Andrés Arauz, appears on course to force a run-off. Regardless of the presidential victor, the unicameral National Assembly is set to remain very polarised.

The return of the traditional right to government would mean policy continuity with the pro-business reforms of the outgoing centre-left Lenin Moreno. However, it would also mean a continuation of the current IMF-supported austerity programme and public sector reform agenda. In the context of a very depressed economy and a restive, potentially uncooperative National Assembly, this intensifies the risk of widespread popular discontent under the new government.

Lastly, Chile is caught up in an electoral Iron Man race that will see voters heading to the ballot box no less than five times between 25 October 2020 and 19 December 2021 for a constitutional reform process, and municipal and general elections. With Chile’s Political Stability Index score having already deteriorated dramatically upon the 2019 unrest, our current forecast sees a (still not inconsiderable) 25.6% risk of a further deterioration in the coming two years. While the constitutional reform process that will dominate the political agenda was launched in response to the 2019 crisis, it is not at all clear that it will fully resolve the demands of Chile’s restive population.

Explore our political risk data & indices

With this reform process running concurrently with the local and general election calendar, Chile is at elevated risk of further outbreaks of social unrest, in what promises to be another politically heated year for the country in 2021. On the face of it, the country’s political class has no ‘Plan B’ to address public demands, meaning that if the Constitutional reform process fails to meet expectations, the two traditional political coalitions, which have alternated in power since the return to democracy, would be even further discredited. In this scenario, an ‘outsider candidate’ in 2021 could represent an attractive break with the status quo for many voters, potentially hindering Chile’s ability to recover the policy stability that has characterised the country for decades.

Electoral Russian roulette will trigger investor uncertainty

Regional experience suggests that the populist political cure can be far worse than the disease. Novice populist outsiders not only tend to lack executive experience, but also the support of a well-oiled national political party. Such presidents typically expend significant capital juggling vested political interests in congress, rather than making policy, meaning that they rarely resolve the deep structural issues underpinning the social grievances that got them elected in the first place.

In countries where economies are tightly linked to major extractive industries, social demands can fuel policy volatility through tax reform, indigenisation, or greater local investment requirements, to name but a few. Increasing populist discourse will likely fuel such moves with an upshot of dimming investor appetite. The stakes could not be higher in 2021, as Peru and Chile, in particular, risk gambling away their positions as Latin America’s most stable economies and favoured FDI destinations.