Demand for hand sanitiser fuelling human rights risks in supply chains

Human Rights Outlook 2020

by Victoria Gama,

Handwashing has emerged as an essential weapon in the fight against the spread of COVID-19. But rising demand for alcohol-based hand sanitiser, and its main ingredient ethanol, will likely come at the expense of human rights and raises the spectre of violations entering corporate supply chains.

According to new data from Verisk Maplecroft’s Commodity Risk Service, the production of sugarcane, which is used to distil ethanol – the key ingredient in the manufacturing of hand sanitiser – already poses a ‘high’ or ‘extreme risk’ of child labour, modern slavery and deforestation in countries such as Brazil, India, Mexico and Thailand. And the situation is likely to worsen.

Register now for our webinar where we discuss this insight in further depth

As of March 2020, the US alone registered a 470% year-on-year rise in sales of hand sanitiser. With demand expected to grow globally, the market value for such products could be worth USD8.09 billion by the end of 2025. The spike in sales means increases in the production of sugarcane will raise ESG (environmental, social and governance) risks in major exporters of the commodity.

With strict travel restrictions still in place in many countries, manufacturers of hand sanitisers and other products containing ethanol will find it increasingly difficult to maintain adequate control of standards in their sugarcane supply chains. Audits of raw material suppliers have proved impossible for Western brands. As a result, workers in producing countries are likely to see labour rights worsen as the sugarcane business booms – driven, ironically, by the need to safeguard the health of people across the globe.

Forced and child labour risks in ethanol supply chains

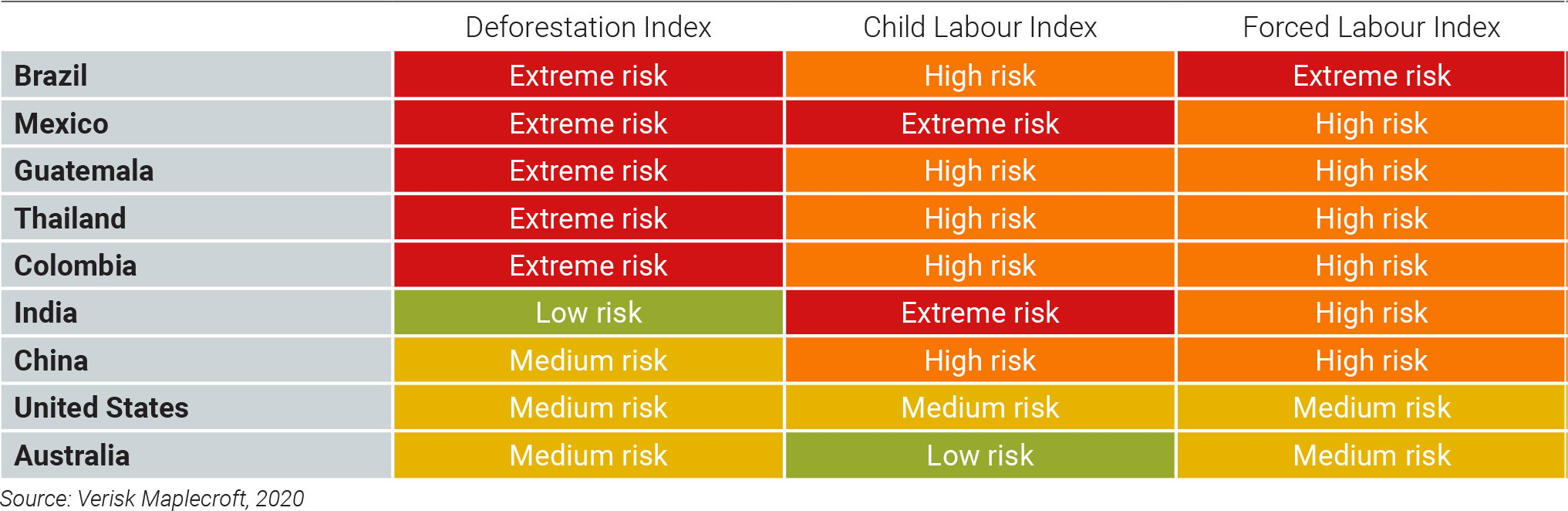

Using a sample of three risk categories from our Commodity Risk Service for the world’s nine biggest producers of sugarcane, we’ve assessed some of the key issues that companies sourcing the crop need to be critically aware of. As shown in Figure 1, the risks are widespread.

Six of the countries – including India, China, Mexico and Guatemala – are already rated ‘high risk’ for forced labour. But given the raised demand for ethanol and the challenges in auditing suppliers, we expect the situation to worsen for workers.

However, it is in Brazil, the world’s largest producer of sugarcane, where forced labour should raise the biggest red flag for procurement departments. With a score of 1.45 out of 10.00 (where 0 is the worst), it is the only country assessed with an ‘extreme risk’ rating for the issue.

Learn more about our commodity risk service

In 2018, the US Department of Labor highlighted sugarcane sourced from Brazil as having a high risk of being produced with forced labour, due to the widely used practice of debt bondage. Although the Brazilian government has made efforts to address the issue, its release of the 2019-H1 ‘dirty list’, which names and shames companies for the use of forced labour, included numerous sugarcane farms.

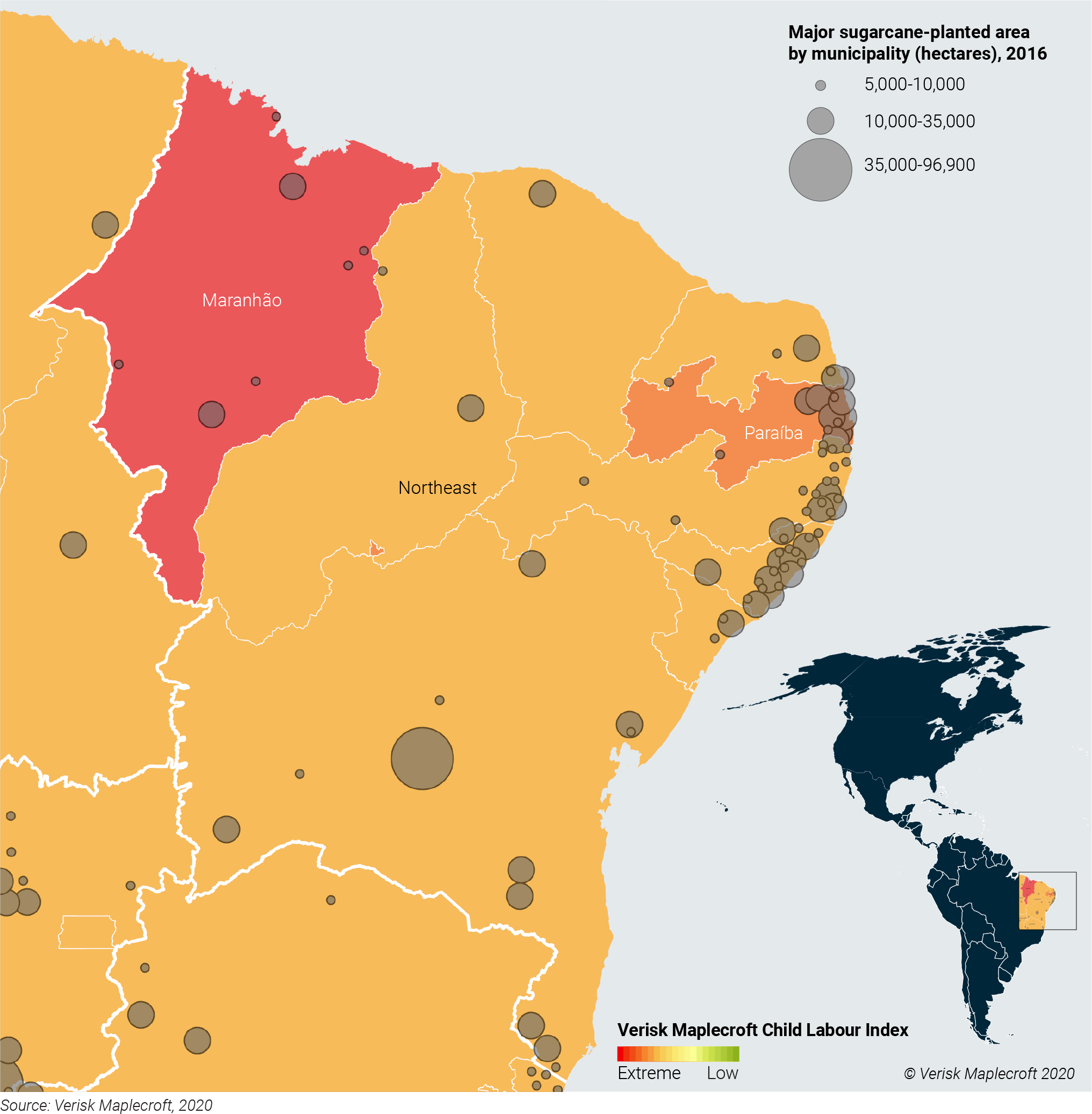

Child labour is also rife in the harvest of sugarcane in the largest producers, most notably in India and Mexico, both of which are rated ‘extreme risk’ in this category of our Commodity Risk scores. The children of Indian migrant labourers have no choice but to work with their parents. The state of Maharashtra, which accounts for 70% of India’s sugarcane production, sees an influx of 200,000 children with their families each year. Similarly, independent studies have found that as many as 30% of Mexican sugarcane harvesters started work between the ages of five and fourteen.

The risks to labour rights in the production of sugarcane encompass a much wider range of issues though, with occupational health and safety chief among them. Under the ‘champion system’ in Brazil and Guatemala, workers are paid for how much they harvest. This results in excessively long working hours in a highly demanding and unsafe physical environment. Machete-related injuries are common, due to a lack of protective equipment, and respiratory problems from burning cane can severely impact worker health.

Forests and indigenous groups not immune

Forests, and those who live in them, will also face higher risks as demand for hand sanitiser rises. As seen in Figure 1, deforestation risks in producing countries are glaring – five of the nine major producers of sugarcane, including Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico and Thailand, are rated ‘extreme risk’ for the issue.

Again, Brazil stands out. It poses the highest risk for the issue, barring Guatemala. While deforestation rates linked to the sugarcane industry have fallen in the country over the past decade, a boom in demand converges with a political drive for environmental deregulation. As a result of policies implemented by the government of President Bolsonaro, the pace of deforestation began to increase in 2019 and has intensified in the first half of 2020.

Download the full report

Human Rights Outlook 2020The rights of indigenous groups located in the Amazon face a clear threat. Based on data collected in the first four months of 2020 by Brazil’s National Institute of Spatial Research, alerts relating to the displacement of indigenous people as a result of deforestation rose 59% compared to the previous year. We anticipate the trend is likely to worsen, as Bolsonaro seeks to push legislation granting titles over land in the Amazon to illegal occupants.

COVID-19 lockdowns will prevent adequate oversight

With brands unable to deploy teams on the ground to audit suppliers, all signs point towards more infringements of workers’ rights, fragile environments and their inhabitants. The rise in ethanol production to contain COVID-19 will, therefore, put some of the world’s most vulnerable workforces and ecosystems at increased risk of abuse. In the current environment, the risk of association or complicity with such violations has multiplied for brands sourcing sugarcane.

The challenge for companies is to understand how and where the risks are highest, otherwise ethically minded consumers and investors could wash their hands of them.