COVID-19: No breathing space for major economy stimulus

by David Wille,

Governments, businesses and individuals around the world have pressed pause in an attempt to slow the fast-moving coronavirus pandemic. Markets, meanwhile, are still looking for a floor. Investors are trying to price in both roiling public health crises and countries’ ability to provide enough fiscal and monetary support to ward off economic collapse and its political and social consequences.

Unfortunately, our data suggest many of the world’s largest economies – including China, India and many developed markets (DMs) – will struggle to do much more than they already have should the slowdown last more than a few months.

Countries with less room for manoeuvre will be at proportionally greater risk of lasting economic damage and in some cases political disorder, as well as slower recoveries in the aftermath.

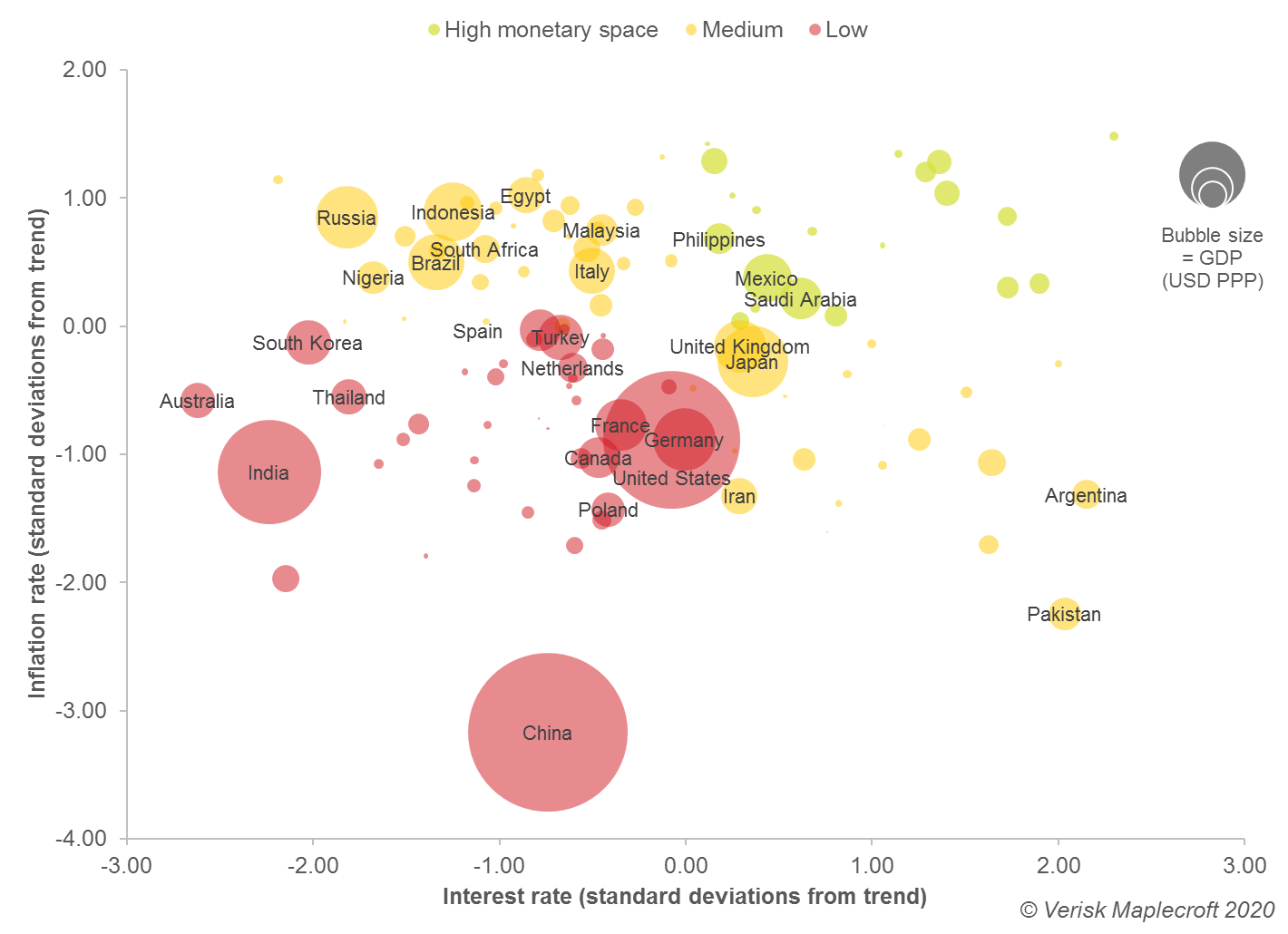

Using our global economic risk dataset, we’ve categorized central banks and government authorities based on the degree of monetary and fiscal flexibility they now enjoy to combat the economic crisis. Central banks that have the least monetary ‘space’ have a combination of low interest rates and high inflation that will make further accommodative policy troublesome.

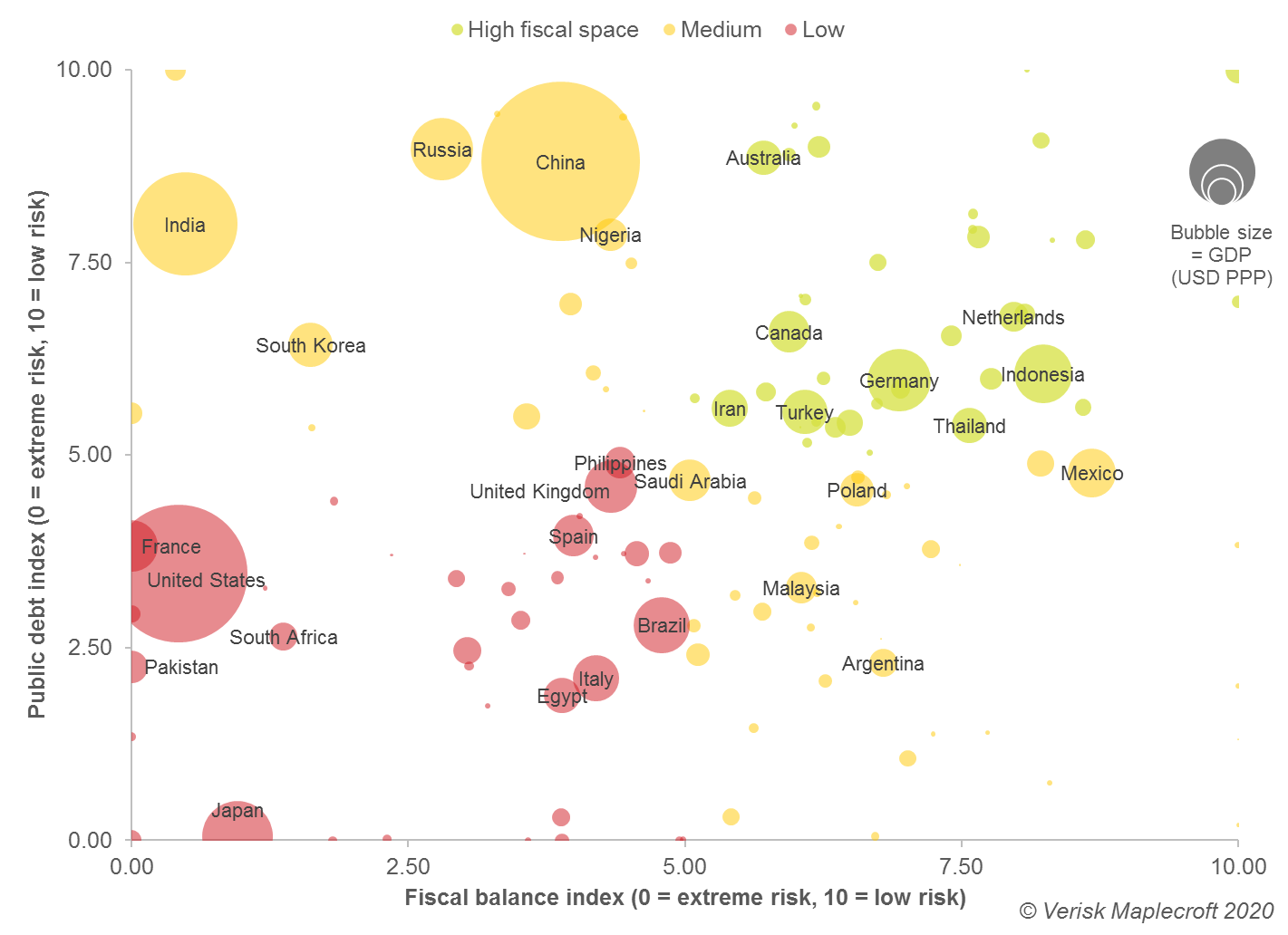

Similarly, governments that have the least fiscal ‘space’ have a combination of high budget deficits and a high public debt load that makes further borrowing to fund relief programs difficult.

Developed markets: set to rely on fiscal measures, but some will struggle with further stimulus

With interest rates already near or below zero, central banks in the United States, Japan, Canada, Australia, and Europe have swiftly run out of room to respond to unprecedented financial market volatility. Most developed market economies now occupy the lower-left quadrant of Figure 1 above, implying they have little monetary ‘space’ remaining. And while most have restarted quantitative easing, injecting liquidity into the financial system, the onus has now shifted to legislatures to deliver fiscal relief.

However, our analysis suggests that many of these governments will quickly run into fiscal constraints as well. Countries enjoying the least fiscal ‘space’ occupy the lower-left quadrant of Figure 2 below, encompassing major developed markets like the United States, France, Japan and the United Kingdom.

This does not mean that these governments will stop borrowing via domestic and international capital markets. Instead, the staggering deficits and debt incurred from just the initial round of stimulus could hinder policymakers from acting decisively when – as is likely – additional rounds of stimulus are required. At worst, they could pressure lawmakers to loosen restrictions on commerce and risk spreading the epidemic further.

Meanwhile, Australia, Canada and Germany – classified as having relatively high fiscal ‘space’ in the top-right quadrant of Figure 2 below – will have more spending flexibility should further rounds of stimulus become necessary.

Emerging markets: with little room to loosen, not all governments will be able to open the fiscal taps

Swift action by DM central banks gave their counterparts in China, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea and Turkey room to cut rates between 20-100 basis points in recent weeks. Unfortunately, this leaves most of the largest EMs in the upper-left quadrant of Figure 1 above, suggesting that they have little left in their monetary toolbox.

Only Mexico still has the monetary flexibility to press forward with central bank stimulus, while rates for the others are now either at or approaching decade-low levels. Further monetary loosening will be less effective as they run into diminishing returns, and in cases like India and China risk exacerbating already-high inflation.

But for many EM governments, the picture is also bleak on the fiscal front. While Beijing on paper has some fiscal flexibility left, it has been hesitant to spend as it did after the 2008/2009 financial crisis given the magnitude of long-running corporate debt strains. Delhi announced a USD23 billion spending plan to transfer cash and necessities to the poorest households, but further support will be needed for its more than one billion citizens facing lockdown.

For countries with precarious budgets and little remaining monetary firepower, like India, governments face difficult trade-offs. Some will attempt to cover their fiscal shortfall with international borrowing, but the risk-off environment is driving up borrowing costs and could threaten debt sustainability. Governments already in crisis may be forced to plead their case to the IMF, as Iran attempted in mid-March. Others may resort to monetising their debt, which risks accelerating inflation and undermining investors’ confidence.

As the economic crisis caused by the coronavirus outbreak deepens, we'll continue both to monitor the sweeping monetary and fiscal tools that governments are deploying and to assess how likely they are to prevent worst-case outcomes.