Latin America in line for huge surge in civil unrest

by Jimena Blanco and Karla Schiaffino and Mariano Machado,

Mass protests in the US have taken recent headlines for good reason, but further south civil unrest is about to boil over in countries across Latin America as the full economic impacts of the pandemic take hold and simmering grievances resurface.

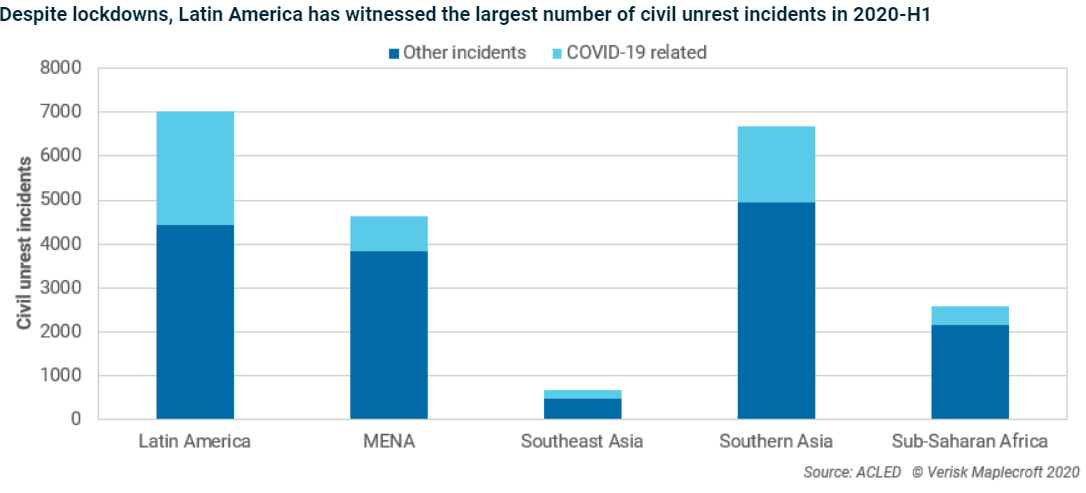

Half the countries in the Americas already sit in the extreme and high-risk categories of our Civil Unrest Index (see below). The region also recorded the highest number of civil unrest incidents globally from February to early June and we expect the trend to worsen over the coming weeks and months with implications for government stability and the business environment.

Economic “hangover” will leave lasting scars

The Americas are heading towards the biggest economic contraction of any region. According to the latest (conservative) IMF projections, GDP declines will range from 6.6% in Mexico to 2.4% in Colombia. Countries face a toxic mix of fiscal constraints from falling tax receipts, alongside spiralling demands for more spending from under-pressure populations.

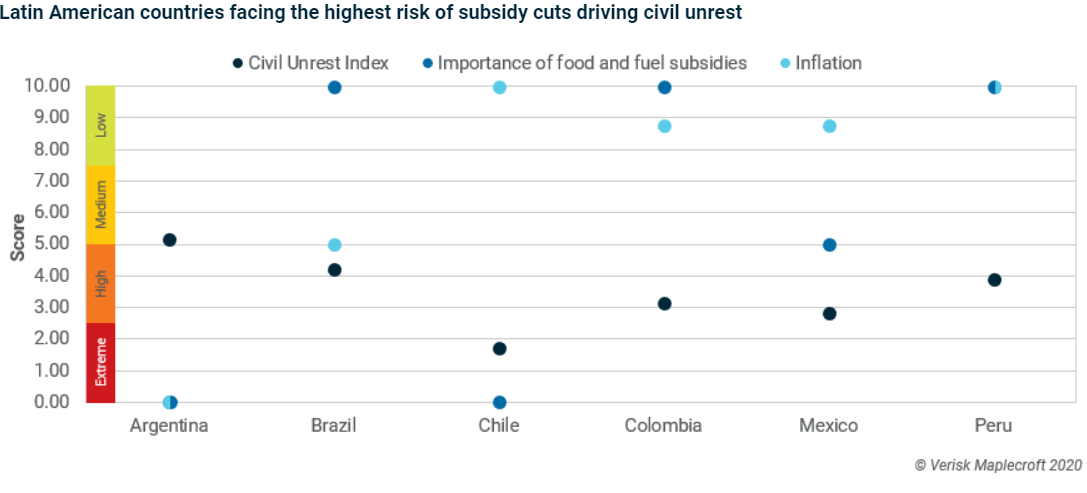

Crucially, food and fuel subsidies will be reduced or removed – a textbook driver of unrest. Indicators from our Civil Unrest Index point to Venezuela, Chile, Paraguay, Ecuador and Argentina as the most exposed to protests from potential reforms to subsidies. Although individual companies are not commonly targeted during episodes of unrest, asset destruction can result in multi-billion-dollar losses, as demonstrated by events in Chile, Ecuador and Colombia in 2019.

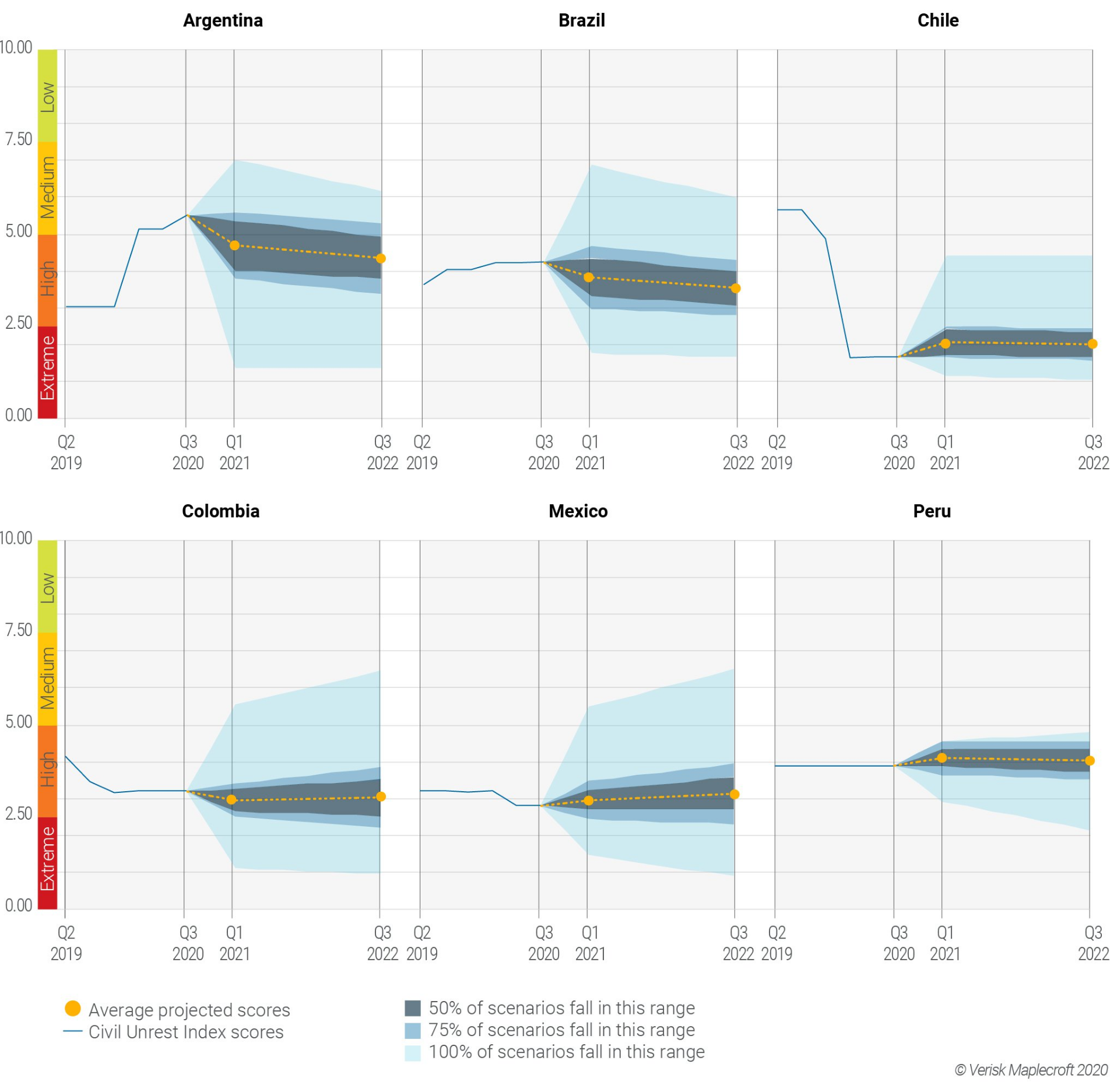

In addition to the economic hit from COVID-19, we expect unrest to spike in the second half of 2020 because pent-up issues that spilled over into protests in late 2019 remain unresolved. Anger over economic inequality, government corruption and human rights abuses are still simmering in the background.

COVID-19 containment measures put the lid back on the pressure cooker; but they also brought economies to a screeching halt. Most countries in the Americas are about to enter a fourth month of restrictions, and patience is on the wane as the economic outlook worsens and democratic processes are eroded through emergency measures.

Data compiled by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) shows that the Americas recorded the highest number of civil unrest incidents during the pandemic (see below). Mexico, Brazil and Chile top the list, in line with their extreme- and high-risk rankings in our Civil Unrest Index.

While most of these events were peaceful, the US dropped into the high-risk category of our index for Q3, falling 53 places in the ranking - to 48th highest risk globally - because of violent demonstrations. Although driven by racial tensions, the economic context played a key role.

The rate of unrest across the region boosts the probability of a disruptive escalation in Q3 and Q4. Our projections indicate that the highest risk is in countries with a recent history of unrest – such as Colombia and Ecuador – and those where major economic contractions are set to push large segments of society into vulnerable positions – like Argentina and Brazil.

Outlook for Chile, Ecuador and Brazil is cause for concern

The economic downturn and the potential collapse of the healthcare system have already sparked demonstrations in Chile. Failure to meet short-term basic needs – such as the slow roll-out of the ‘Food for Chile’ programme – drove some incidents and underscored the inequalities that motivated protests and riots in 2019.

The 38% rise in lay-offs between March and May pushed unemployment to 9% in 2020-Q1. With the pandemic reducing purchasing powers and curtailing access to healthcare and education, we expect demands for change to return with greater force when restrictions are lifted and the country holds a constitutional reform referendum.

In Ecuador, the government’s fiscal austerity programme, which sparked the 2019 street protests has returned to the top of the political agenda as the country battles one of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks in Latin America. Changes to allow job dismissals with lower compensation will also expand participation, with the urban middle class likely to support a movement that had previously mobilised rural and indigenous groups.

It’s a different story in Brazil. President Bolsonaro’s underplaying of the pandemic and open confrontations with other government authorities over containment measures has triggered ‘pots and pans’ protests throughout March and April. The intensifying political crisis - with rallies in favour of closing congress and the supreme court – resulted in pro-democracy, anti-government demonstrators taking to the streets and clashing with pro-Bolsonaro groups and the police in late May.

Concerns over Bolsonaro’s democratic credentials are not new. But with judicial investigations potentially leading to an impeachment process and local elections due in October, political and economic concerns are set to deepen the risk of protests from both sides of the political divide.

Pandemic will amplify existing inequalities behind mass unrest

The fallout from the pandemic is going to worsen basic inequalities and act as a catalyst for further unrest. In a region with high levels of poverty and worker informality, more people will be pushed into lower-paid, unstable, part-time and/or informal jobs.

It is the young that will be disproportionately affected, which will reinforce the trend of mass mobilisations organised through social media. Dissatisfied – and often disenfranchised – young protesters have led some of the most disruptive protest movements in the past five years.

All things considered, a severe escalation of unrest in the region is probably now inevitable. The question is just how bad will it be?