Digital infrastructure is now the backbone underpinning the global economy. Its continuity is not just fundamental to business—it is existential. From financial markets and supply chains to e-commerce and banking services, reliance on these critical networks and the services they support is central to company operations the world over.

The importance of these networks mean they represent a source of vulnerability to business that is compounded by the fact they are often owned and operated by third parties. Regulators, particularly in the financial services sector, are moving towards addressing the growing reliance on third-party ICT service providers through specific requirements in operational resilience regulations, including active interrogation of critical vendor contingency plans.

However, guidance on operational resilience has traditionally concentrated on cyber security and contingency arrangements for system failures. But risks posed by the external operating environment, and by the proximity of third-party operations to each other, also present a source of vulnerability arising from location and spatial arrangements. Understanding these vulnerabilities is challenging, but applying location-specific risk data can quickly identify potential threats and pinpoint where risk reduction efforts should be focused.

Unlocking risk management insights by assessing external risks

External events such as natural hazards, political violence or disruption to energy or water supplies can interrupt digital infrastructure services or take them offline. The impacts can depend on a facility’s location:

1. Site-specific exposure: Facilities can be individually vulnerable to traditional security threats and natural hazards, which may cause direct physical damage, block access routes, or affect utilities.

2. Proximity of sites to each other: The locational relationship of sites—such as power sources or backup facilities—to each other also presents a potential source of risk. An acute external event that can affect more than one location simultaneously may render contingency measures ineffective if their proximity to each other has not been considered (see Figure 1). For example, during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, some data centres in Manhattan with backup sites in New Jersey suffered impacts at both locations and could not maintain services. This type of vulnerability can also apply when multiple vendors have a presence in a concentrated area. For example, ‘Data Center Alley’ in Northern Virginia, where a single external event could create simultaneous disruption.

1. Site-specific exposure: Building individual site risk profiles to plan for threats

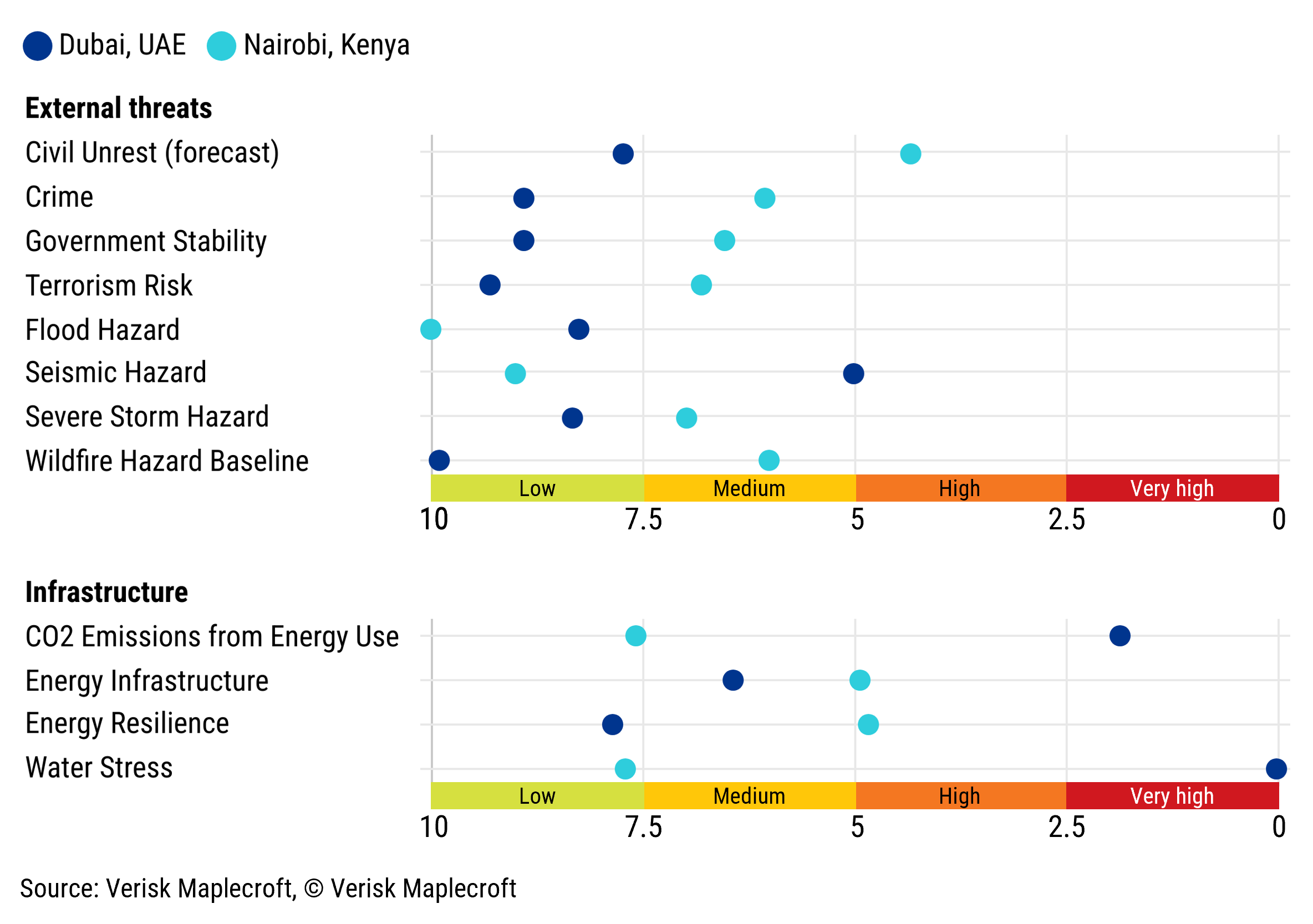

Consider two hypothetical data centres located in Dubai, UAE and Nairobi, Kenya. Insight into the external risk profile of each location can inform targeted investigations into the robustness of third-party contingency arrangements to ensure they adequately mitigate these risks based on their assessed impact and duration.

Figure 2 shows the risk profile for a selection of external threats and infrastructure considerations at both locations using Verisk Maplecroft’s Country Risk Data.

The data shows a stark contrast in the external threats facing these locations and highlights that different approaches are needed to address these risks.

The facility in Nairobi faces higher levels of social and security risks that may arise from civil unrest and government collapse, while also facing moderate risks from severe storms and wildfires. Crime and terrorism risks are also present. This multi-risk profile indicates contingency measure that anticipate disruptions on a fairly frequent basis should be in place.

In contrast, while Dubai faces low risks from most of the security and natural hazards assessed and may therefore expect to experience a lower frequency of routine disruptions from external incidents, its exposure to earthquakes could potentially result in extended downtime. Scrutiny of the building standards, alongside an evaluation of the contingency arrangements for such high impact events is required to establish how resilient this facility is over the long term.

Examining power and water considerations, although Dubai’s energy security and comparatively robust infrastructure is reassuring, extreme levels of water stress, coupled with very high energy-related CO2 emissions, suggest further investigation into the operator’s long-term energy strategy is warranted.

Nairobi’s poorer performance on energy security and energy infrastructure could raise concerns over the ability to deliver stable and reliable power, particularly if the ICT sector expands here and energy demands continue to grow.

2. Proximity of sites: Understanding where third-party risks are concentrated

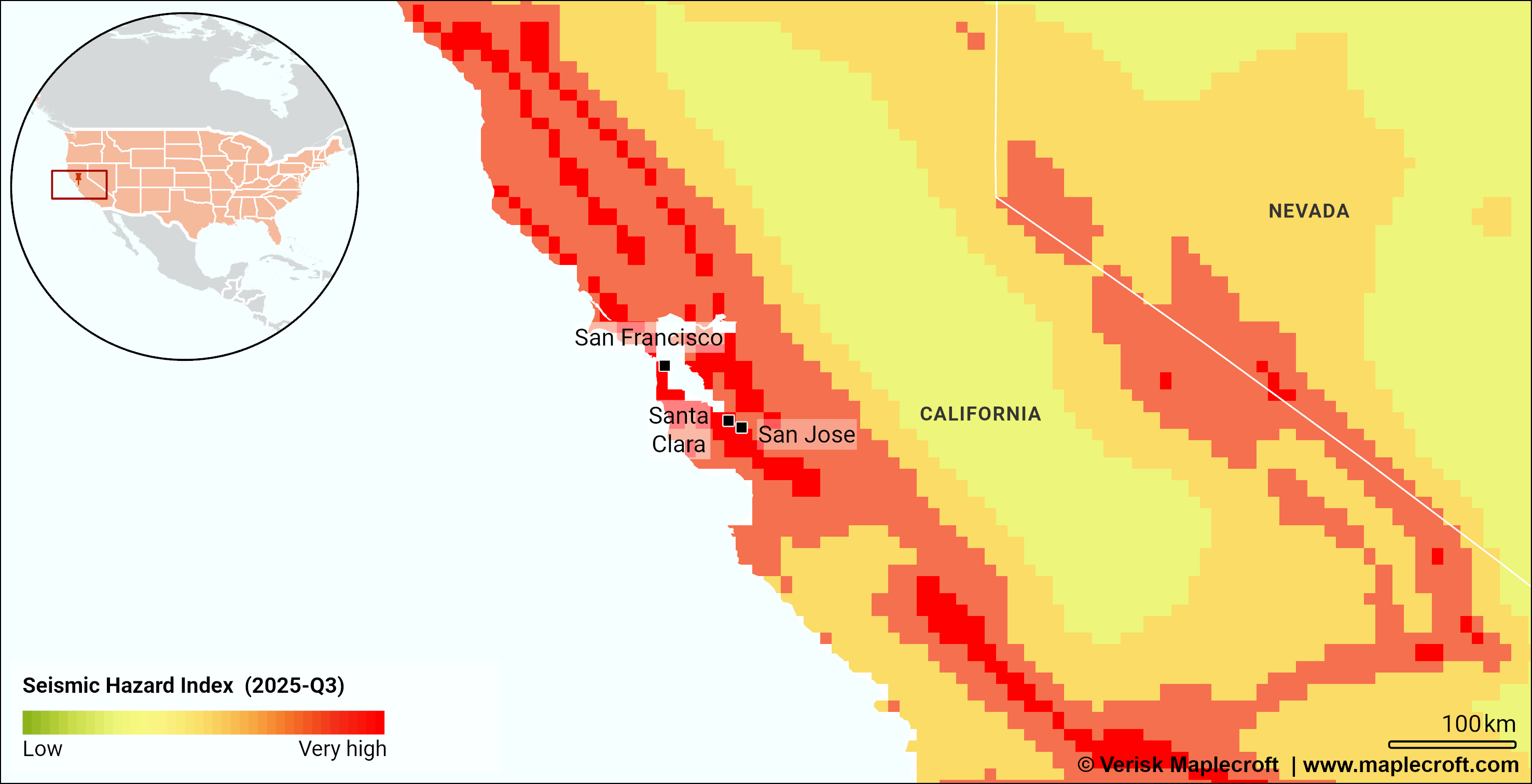

Understanding the interdependence and concentrations of third-party service provider locations is equally important to ensure the viability of failover and contingency plans. After Hurricane Sandy illustrated the pitfalls of using highly concentrated backup sites, US regulators encouraged companies to “consider geographic diversity when determining the physical location of alternative sites”, highlighting that “an alternative site […] in close proximity to the primary site may not sufficiently protect the firm from the effects of a region wide event”.

Figure 3 shows an example of three data centre hubs—San Francisco, Santa Clara, and San Jose in California—all of which lie close to the San Andreas Fault and are exposed to this single source of seismic activity. While failover from, for example, a data centre in San Francisco to one in Santa Clara would mitigate the impact of an earthquake localised to San Francisco, this may not be a viable contingency for a regional seismic event.

Conclusion

Reliance on third-party digital infrastructure is set to grow in line with the expansion of AI and cloud-based services, while external threats, such as climate change, are projected to intensify. Taking a data-led approach to identifying spatial vulnerabilities in such networks is more crucial than ever before to building operational resilience.