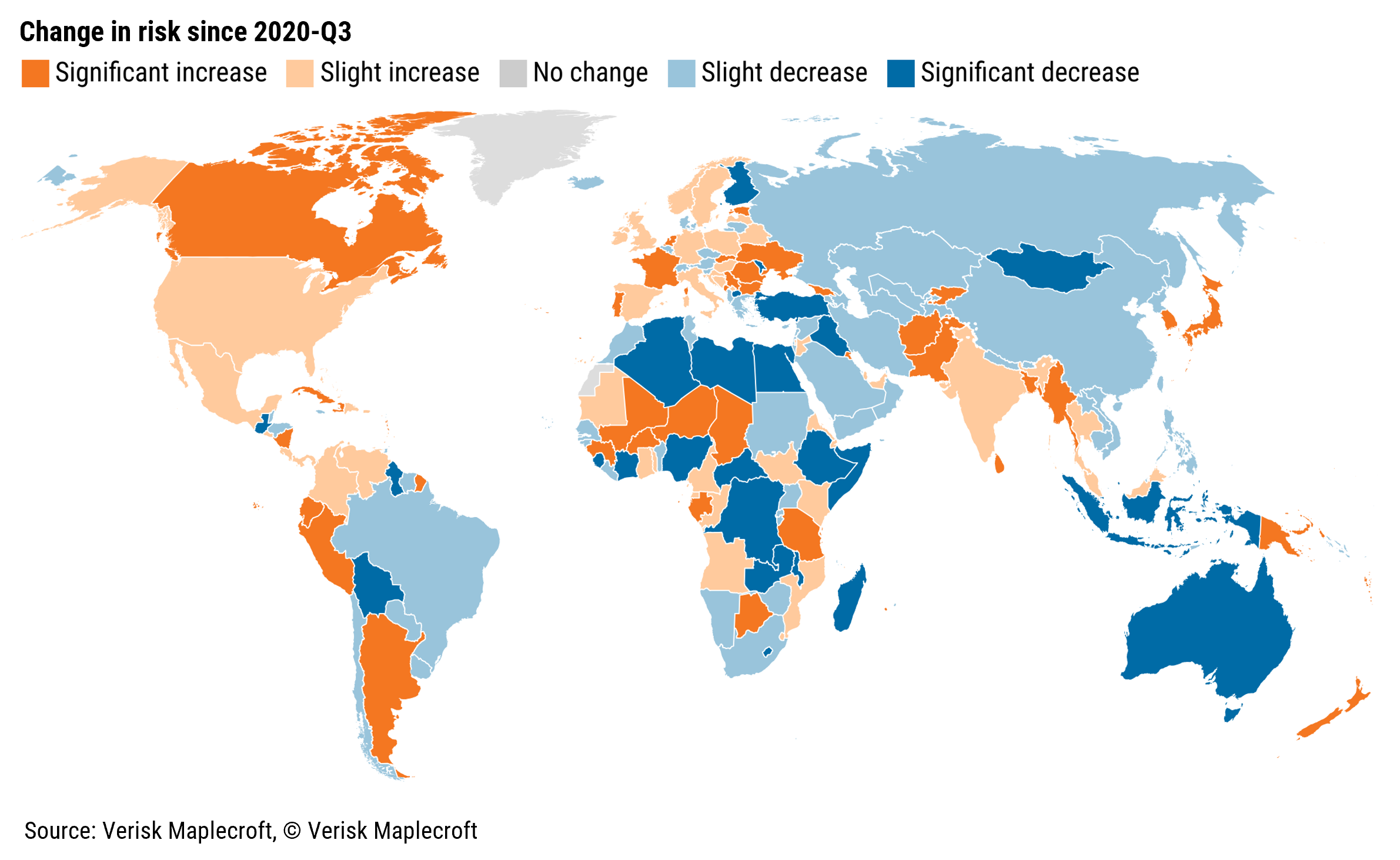

Government instability is on the rise globally according to our new research which signals potential market volatility for investors – including in some of the world’s key developed economies. In total, 43 countries, home to a quarter of the assets of the companies in the world’s largest stock markets, have seen a substantial increase in risk on our data measuring the issue since 2020.

Significantly, the analysis shows government instability is moving closer to home for Western investors and companies. Alongside a swathe of emerging markets, including Argentina, Bangladesh, Serbia and South Korea, developed economies, such as France, Canada, Japan and the Netherlands have all witnessed an uptick in risk, which we class as ‘significant.’

Against a backdrop of intensifying geopolitical competition, disruption to global trade flows and fiscal tightening, the data captures a key aspect of political risk by evaluating 198 countries on the strength of executive authority, the potential for irregular and regular transfers of power and how well a government can implement its policies.

Government stability is fundamental for investors, as it makes policy decisions more predictable and enables more accurate asset valuations and longer-term strategic planning. A widening trend of government instability in developed economies could spell trouble, as markets have generally priced in a higher likelihood of sudden political disruption in emerging economies.

Safe developed markets vs risky EMs story not holding

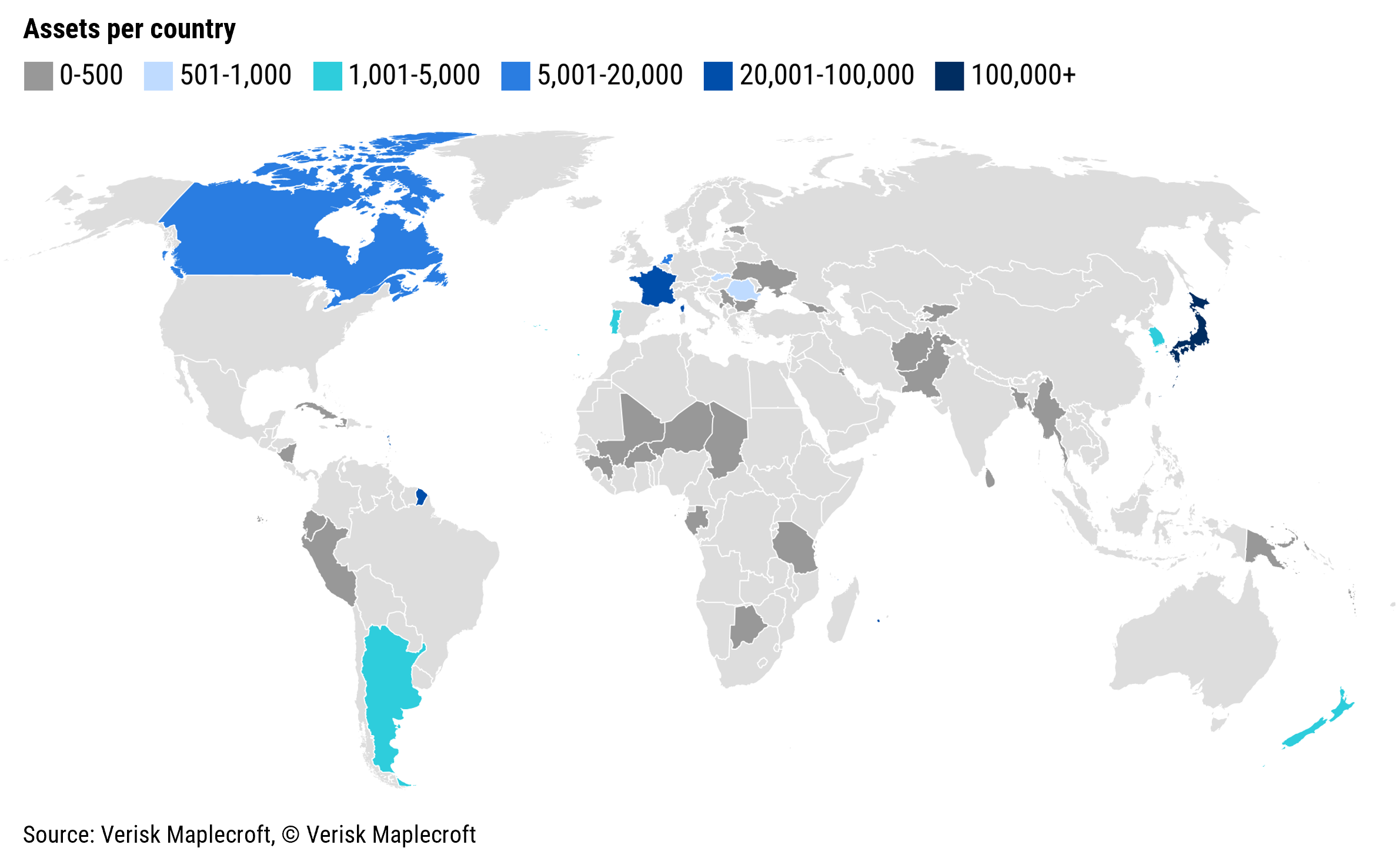

While equity investors typically understand how to navigate political risk in their domestic markets, they may be less aware of the hidden political vulnerabilities embedded in the international operations and foreign assets of the companies they invest in.

The analysis draws on our Asset Risk Exposure Analytics (AREA) to look at the global locations of the 800,000+ corporate assets in the Nikkei 225, S&P 500, DAX, and FTSE 100. Overall, 26% of the corporate assets of these stock markets are in countries that have seen a significant uptick in political risk.

When looking at foreign assets alone, developed markets make up 92% of countries where political risk is increasing, leaving the established narrative of safe developed markets versus risky emerging markets looking harder to justify.

Rising political risk in developed markets more disruptive to investors

South Korea (currently 61st highest risk in the overall ranking) and Serbia (46th) stand out among the list of 10 countries seeing the greatest rise in risk, which is otherwise dominated by frontier and conflict-affected states.

But look lower down the list of countries where stability has significantly worsened and Japan (33rd highest risk), Canada (63rd), Netherlands (71st), France (138th), and Portugal (146th) appear alongside emerging markets where political risk is a more established factor, including the likes of Bulgaria (27th), Peru (40th), Romania (81st) and Argentina (117th).

“Political risk in developed markets can be more disruptive to companies and investors because the impact and exposure is higher,” adds Wolf. “Risk management processes are generally geared towards political risk in emerging markets – instability in developed markets points to the potential for market volatility and repricing if the direction of travel continues.”

The reasons for the increase in government stability across developed markets vary, but the resulting impact on business is largely consistent. Companies either have to wait excessively for policy decisions to be made and implemented, or they are subject to reversals of position from new administrations or fragmented legislative bodies, which can stall or derail investment strategies and planning.

Just this week, political instability culminated in the collapse of governments in Japan and France, two of the world’s largest developed economies. In France, Prime Minister Bayrou lost a confidence vote on 8 September, leaving the country set to appoint its seventh prime minister since 2020. With presidential elections not scheduled until 2027, instability is likely to persist. In Japan, a revolving door of prime ministers have struggled to address political scandals and rising living costs since 2020. French bond yields are now among the highest in Europe, reflecting rising investor concerns over the country’s debt. French equities have already lagged behind this year’s broader European rally, and lingering uncertainty over potential corporate tax hikes to address the deficit is likely to keep weighing on sentiment. In Japan, the yen weakened against the dollar, while markets await clarity on who will succeed Prime Minister Ishiba.

Government instability can also be accompanied by rising civil unrest. In Bangladesh, a large spike in political risk has been mirrored by a comparable surge in protest activity, while Serbia has been downgraded from low to medium risk across our data assessing both issues over the past five years.

Renewables most exposed sector to political instability in developed economies

Extractive industries, including oil and gas firms and mining companies, are top of the list when it comes to investors’ awareness of political risk. But data from AREA shows that it’s not the usual suspects when it comes to increasing government instability across major markets. For the DAX, the renewable energy sector is most exposed, with 38% of assets at heightened political risk. Similarly, renewables and transportation are the most-exposed sectors for the FTSE 100.

While political risk has historically been priced into sectors like oil and gas and mining, the rising exposure of renewables is often overlooked. This leaves investors vulnerable due to underdeveloped risk frameworks, misallocated due diligence, and a persistent focus on legacy sectors that no longer reflect the evolving geopolitical landscape. This mismatch can distort asset valuations and lead to systemic under-pricing of risk in portfolios increasingly weighted toward energy transition assets.

Political risk should be a key model input, not an afterthought

Rising trade frictions, cost-of-living pressures, geopolitical competition, and the rise of populist parties are fuelling political volatility globally, with developed markets particularly exposed. For investors, this challenges traditional assumptions and demands a more granular approach to risk across portfolio construction, investment selection, and portfolio management.

DM/EM labels are no longer sufficient as proxies for stability. Country-level risk budgets with explicit political-risk limits, built systematically into models, are essential. That requires visibility into where companies operate and earn, not just where they are listed. At the same time, instability creates openings as well as threats. Political shocks often trigger indiscriminate sell-offs, creating opportunities to buy resilient companies at discounts and to position in sectors that stand to benefit from new policy regimes.

In short, investors who integrate political risk at the corporate level will be better equipped both to protect capital and to capture differentiated returns in an increasingly unstable world.