This year’s World Day Against Child Labour is an important marker, as the elimination of child labour in all its forms by 2025 was a fundamental goal enshrined in Target 8.7 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Although there has been genuine progress – with 86 million fewer children now in child labour than a quarter of a century ago – the most recent UN estimates showed that 160 million children were still engaged in child labour at the start of this decade. Of these, almost half were involved in hazardous work threatening health, safety and moral development.

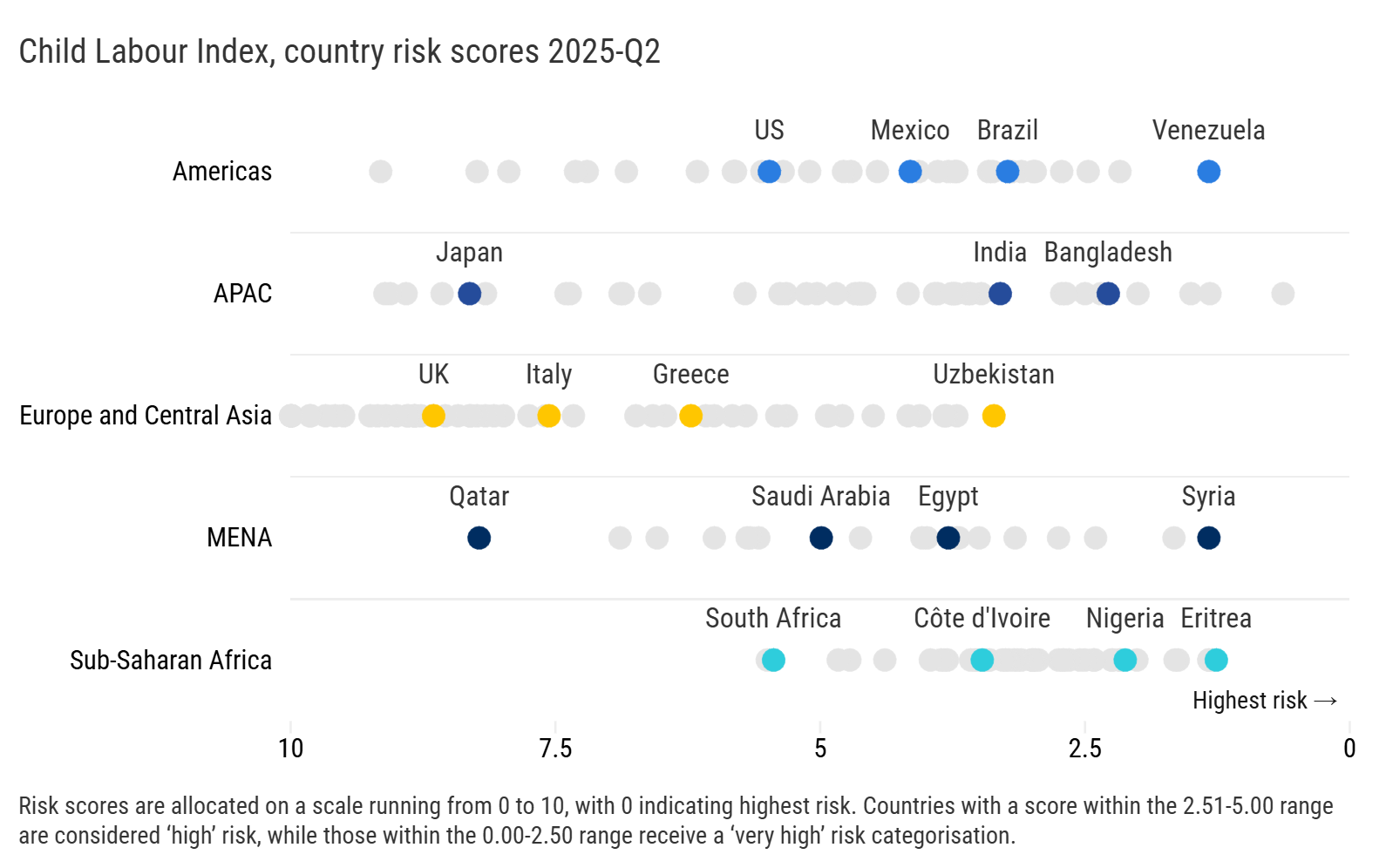

This trend is mirrored by the latest data from our Child Labour Index (CLI). While 49 countries have seen a significant improvement on the index since 2020, 115 – including major emerging economies like India, Brazil, Mexico and Indonesia – remain within the ‘high’ or ‘very high’ risk categories (the two highest in the CLI). At the same time, progress on combatting child labour has stalled, or even reversed, in several advanced economies. Risks remain particularly high in globally significant sectors that are central to supply chains, such as agriculture, mining and manufacturing, according to our Industry Risk Data.

The data makes clear that child labour remains a pressing and persistent risk for multinational businesses and investors, particularly as shifting regulatory and geopolitical dynamics add new layers of complexity to the global operating environment.

Child labour is not just an emerging market issue

The CLI, which like all our human rights indices is based on the UN’s ‘structure-process-outcome’ configuration, examines the strength, enforcement and infringement of child labour laws globally. The index feeds into most of our business and financial risk solutions, including our Sovereign ESG Ratings, Asset Risk Exposure Analytics (AREA), Industry and Commodity Risk Data, and our Corporate ESG Reporting and Sustainable Supply Chain tools.

As we reported a year ago, child labour is not just an ‘emerging market’ issue, and thus far this decade, outcomes in some of the world’s wealthiest economies have shown a statistically significant deterioration, including oil-states in the Middle East and some European countries, alongside emerging markets such as Costa Rica and Bangladesh. In fact, at the aggregate level, every region has posted a deterioration in outcomes on our Child Labour Index in the five-year period to 2025-Q2, except for Europe.

In part, this can be traced to recent global economic strains (as well as intensifying climate and conflict-related drivers), but also, and more notably, the index is flagging up some strains on protections. In major sourcing jurisdictions such as Bangladesh and Cambodia, for example, our data shows that the adequacy of local programmes to prevent child labour has declined over the past five years. Even in New Zealand – typically considered a low-risk environment for human rights – the data indicates that the number of labour inspectors is not compliant with the ILO standard.

This trend, evident across much of our human and labour rights data, appears linked to evolving political and legal environments, which are negatively impacting human rights protections, labour standards and their enforcement across key economic sectors.

Usefully, the Child Labour index has sub-national coverage assessed at first administrative level (i.e. states, provinces, or regions). It effectively assesses some 3,600 administrative areas globally, for a closer understanding of the exposure risk. This can take on added importance for companies and investors operating in or with exposure to federal-type jurisdictions, where states may have a higher degree of regulatory independence and/or enforcement power.

Regulatory and geopolitical dynamics creating further challenges

Whereas a year ago investors and corporates were grappling with an expanding raft of regulations on reporting and due diligence, now they are facing a whole new set of challenges.

First, supply chains are up in the air amid intensifying geopolitical tensions and the global trade war, creating major sourcing uncertainties. Second, regulations that 12 months ago appeared to be tightening (and standardising) are currently going in the opposite direction, while also fragmenting by region, which is creating further layers of uncertainty.

With regulatory reviews (ostensibly in support of consolidation and ease of implementation) taking place in key jurisdictions including the EU – affecting global benchmarks such as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the (up-for-repeal) German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG) – there is now a very real prospect of disparate and regionalised due diligence and reporting frameworks. This could not only increase costs and complexity after several years of efforts to harmonise global standards, but it might also raise the rate of compliance ‘error’.

To minimise disruption, as well as significant legal and reputational risks, multinational companies will be best served by sticking to a ‘beyond compliance’ approach. That means taking proactive steps to identify and address human rights risks across global operations and supply chains, in line with the UNGPs. Moreover, lenders and institutional investors (and potentially also shareholders) will almost certainly require this over the long term. As the risk landscape evolves, companies that embed cutting-edge data and expert insight into their strategies and decision-making processes stand the best chance of keeping ahead of the curve.