On 28 April 2025, a massive power outage across Spain and Portugal triggered widespread economic disruption and national security concerns, underscoring the persistent vulnerability of modern energy systems. Even in highly developed markets with robust clean energy integration, infrastructure failure can escalate rapidly into national emergencies. This incident reinforces the critical importance of energy security in energy transition strategies. Balancing security, affordability and sustainability — the three pillars of the energy trilemma — is becoming increasingly complex. These challenges are even more acute for developing economies. Limited access to reliable power, volatile energy costs and heightened geopolitical risks place resilience at the forefront of national priorities.

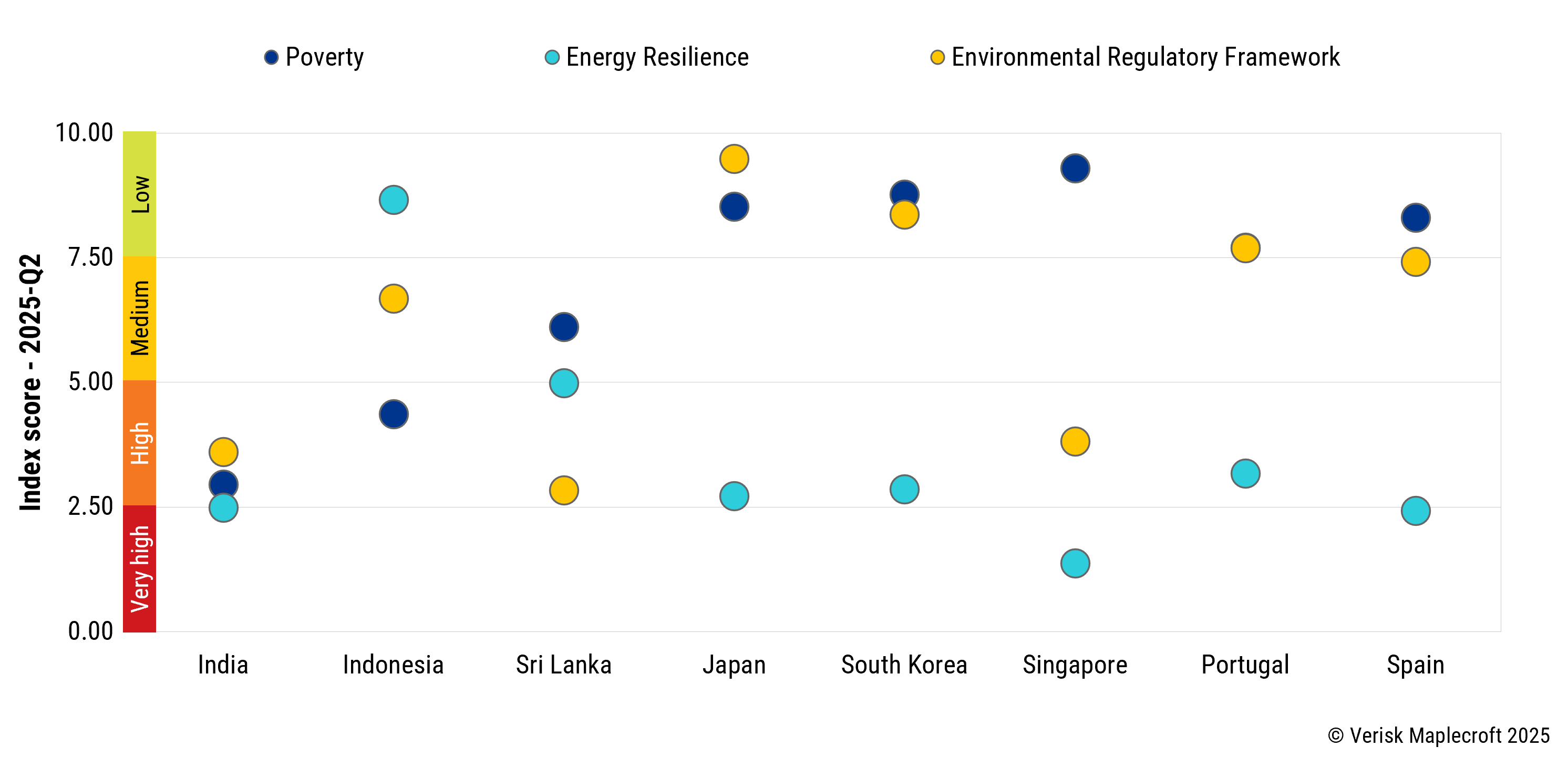

The Asia Pacific region clearly illustrates these structural pressures. Our latest risk data shows that no major Asian economy — whether emerging or advanced — maintains low risk scores across energy resilience, poverty vulnerability, and environmental regulatory frameworks simultaneously. Similar to Spain and Portugal, at least one of these risks remains in the high to extreme category for every market assessed, including developed economies such as Japan, Singapore and South Korea. These vulnerabilities reinforce why many economies — regardless of development status — are balancing decarbonisation efforts with a continued focus on energy security.

Index scores for our Poverty, Energy Resilience and Environmental Regulatory Framework Indices, 2025-Q2

Globally, while the expansion of renewable energy has been significant — with wind and solar now supplying 15 percent of global electricity generation — fossil fuels remain dominant. In 2024, global oil and coal consumption reached record highs, and fossil fuels still accounted for approximately 80 percent of global primary energy mix, only marginally lower than the 85 percent in 1990. This contrast highlights a key reality: the energy transition is not yet displacing fossil fuels at scale, especially in emerging markets where full renewable substitution remains a longer-term ambition, reinforcing the need of developing alternative low-carbon solutions.

In response, governments are increasingly adopting a dual-track strategy: expanding renewables while also investing in low-carbon solutions that enable continued fossil fuel use with lower emissions. Policy support is intensifying around hydrogen industries, carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies for hard-to-abate sectors, low-carbon fuels for the maritime and aviation sectors, and expanding carbon markets to incentivise corporate decarbonisation. These measures are not only critical for accelerating interim emissions reductions but also for maintaining flexibility in transition pathways as economies adapt to evolving technological, political and security conditions.

Who sets the standards for low-carbon solutions?

As alternative low-carbon solutions gain greater policy focus, fragmentation is emerging over their definitions, highlighting the absence of common global standards for investment. While the credibility and commercial viability of these solutions will depend heavily on internationally adopted rules, certifications and methodologies, major economies and corporations are increasingly defining low-carbon investments based on their competitive advantages. For example, the European Union (EU)’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) seeks to shape trade flows by linking carbon intensity standards to EU’s carbon pricing. Without broader participation in the design of such standards, many emerging economies risk remaining passive rule-takers, reinforcing structural disadvantages in global markets.

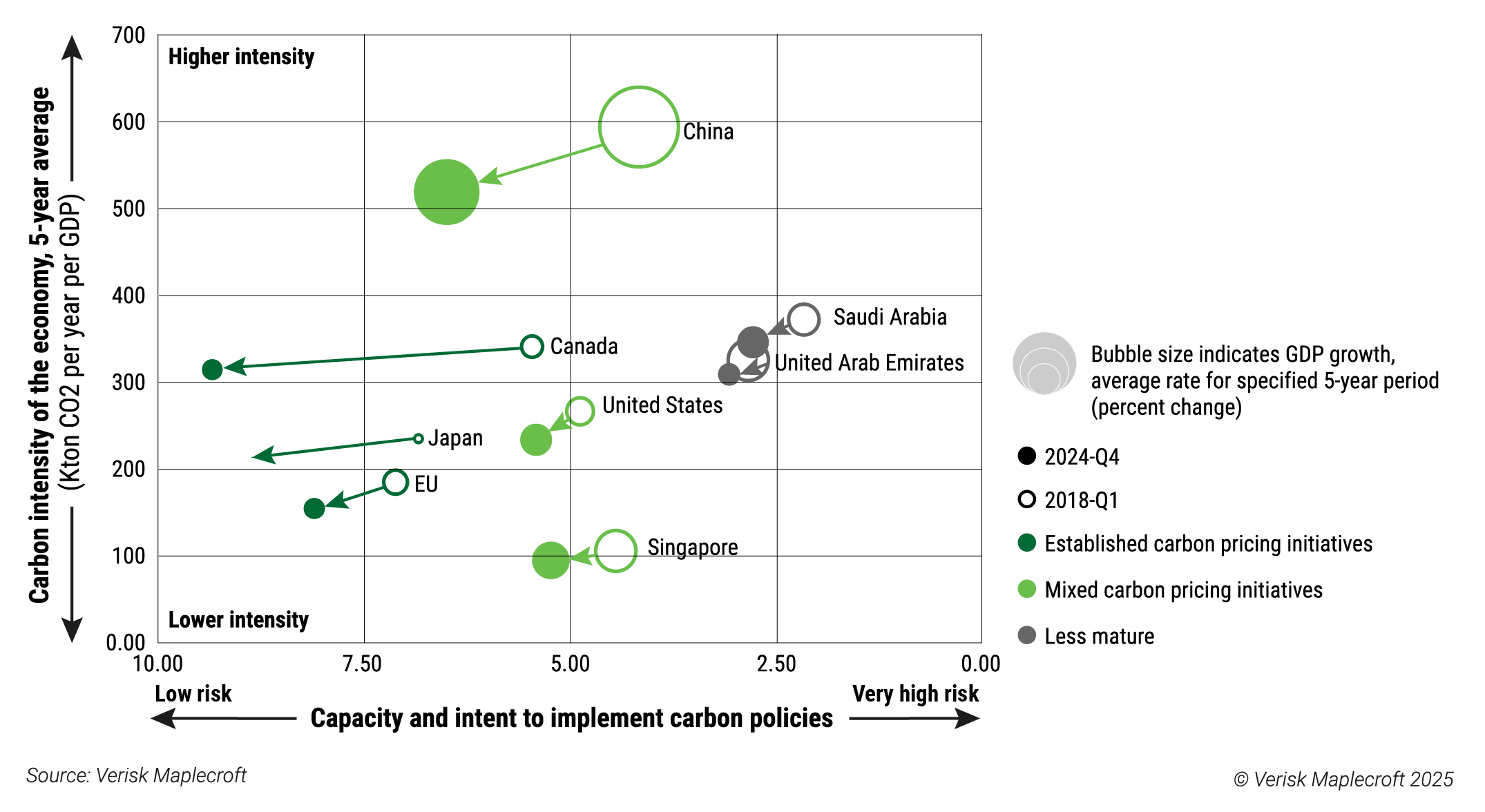

Countries with stronger policy ambition and transition progress are increasingly well-positioned to shape these evolving rules. Our data shows that since the Paris Agreement, economies across Asia, Europe and the Middle East have made steady progress in reducing carbon intensity and tightening domestic climate frameworks. While the EU continues to lead standards development, China is rapidly emerging as a key influencer, combining domestic decarbonisation with active rule-making in areas like carbon markets and green fuel certification. In contrast, the US’s inconsistent direction has limited its policy intent and capacity, creating a leadership gap in global climate governance.

The new battlefield: standards, not just tariffs or sanctions

The weakening of US climate leadership is creating new opportunities for Asia and other emerging markets to shape the global energy transition agenda. Beyond domestic policy shifts, Asian economies are also becoming more assertive in defining their own transition strategies rather than following Western frameworks. For example, China’s development of national carbon market rules and ASEAN’s efforts to align regional carbon trading frameworks point to a broader decentralisation of climate governance — challenging the traditional dominance of Western-led standards.

In the evolving energy transition landscape, standards will increasingly become a new battlefield in geopolitical competition. Emerging markets are no longer merely passive participants in this process. The race to define what qualifies as low-carbon, how emissions are measured, and which technologies are prioritised will shape industrial strategy, market access, and competitive advantage in the coming decade.