Conflict in the Middle East is once again stress-testing the global energy system. Following Israeli and US airstrikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, Iranian law makers have urged the top leadership to consider closing the Strait of Hormuz—a vital chokepoint for 30% of global oil and 20% of LNG supplies. Since the conflict began, Brent crude briefly climbed above $80/bbl on precautionary buying, but has remained moderate due to stable market fundamentals, including high inventories and available OPEC+ spare capacity. Still, the fear of disruption along Hormuz continues to shape trade flows and energy policy, with Asia being the most exposed region.

Yet the real story extends beyond short-term price movements. Geopolitics is increasingly shaping how both buyers and policymakers define and pursue energy security.

Asia’s frontline exposure: Structural vulnerabilities and supply risk concentration

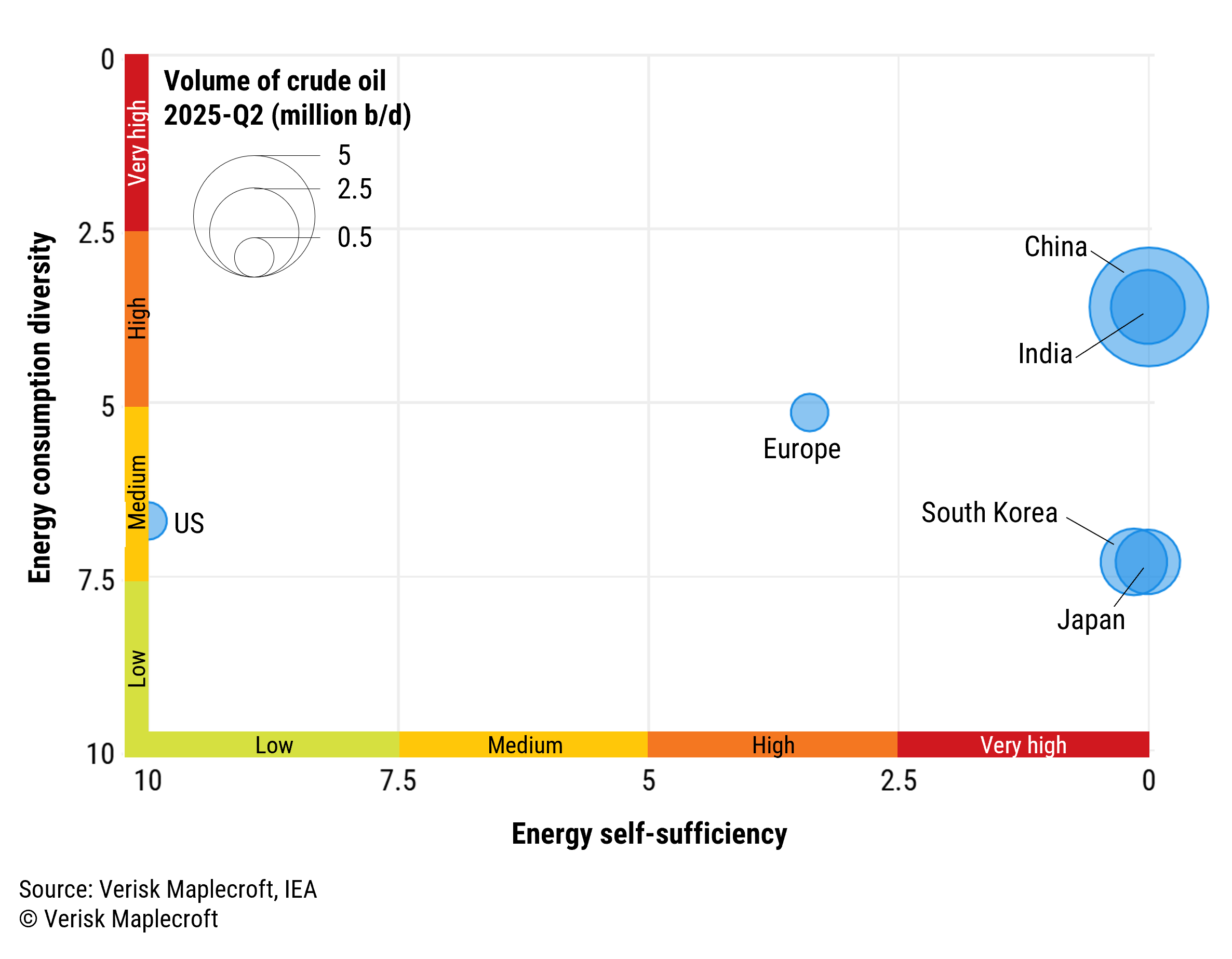

As the primary importers relying on the Strait of Hormuz, Asian markets—unlike the US—would face a disproportionate impact in the event of a disruption. In 2024, China, India, Japan and South Korea alone accounted for 69% of crude oil imports passing through the strait. This is reflected in our Energy Resilience Index. As shown in Figure 1, Asia importers score very high-risk on the index’s energy self-sufficiency indicator and medium-to-high risk on the energy consumption diversity indicator—reflecting limited domestic production capacity and concentrated demand patterns. For Asian importers, including, China, India, Japan and South Korea, any supply gap would be harder to offset domestically compared to their European and US peers, and would likely require sourcing from alternative suppliers at higher cost and with limited short-term flexibility.

A serious supply shock could drive oil prices back toward 2022 levels, when Brent exceeded $100/bbl. Even in the base case of continued flows, the Strait of Hormuz still presents elevated operational risks, shipping delays and rising insurance costs. However, a full closure remains unlikely given Iran’s limited naval capability, the risk of severe economic blowback, diplomatic pressure from key Asian trade partners and the likelihood of stronger US military action. Further, in the event of actual disruption, OPEC would likely step in to stabilise the market by adjusting production to offset lost Iranian supply.

Energy strategy rewired: Beyond price, geopolitics drives risk planning

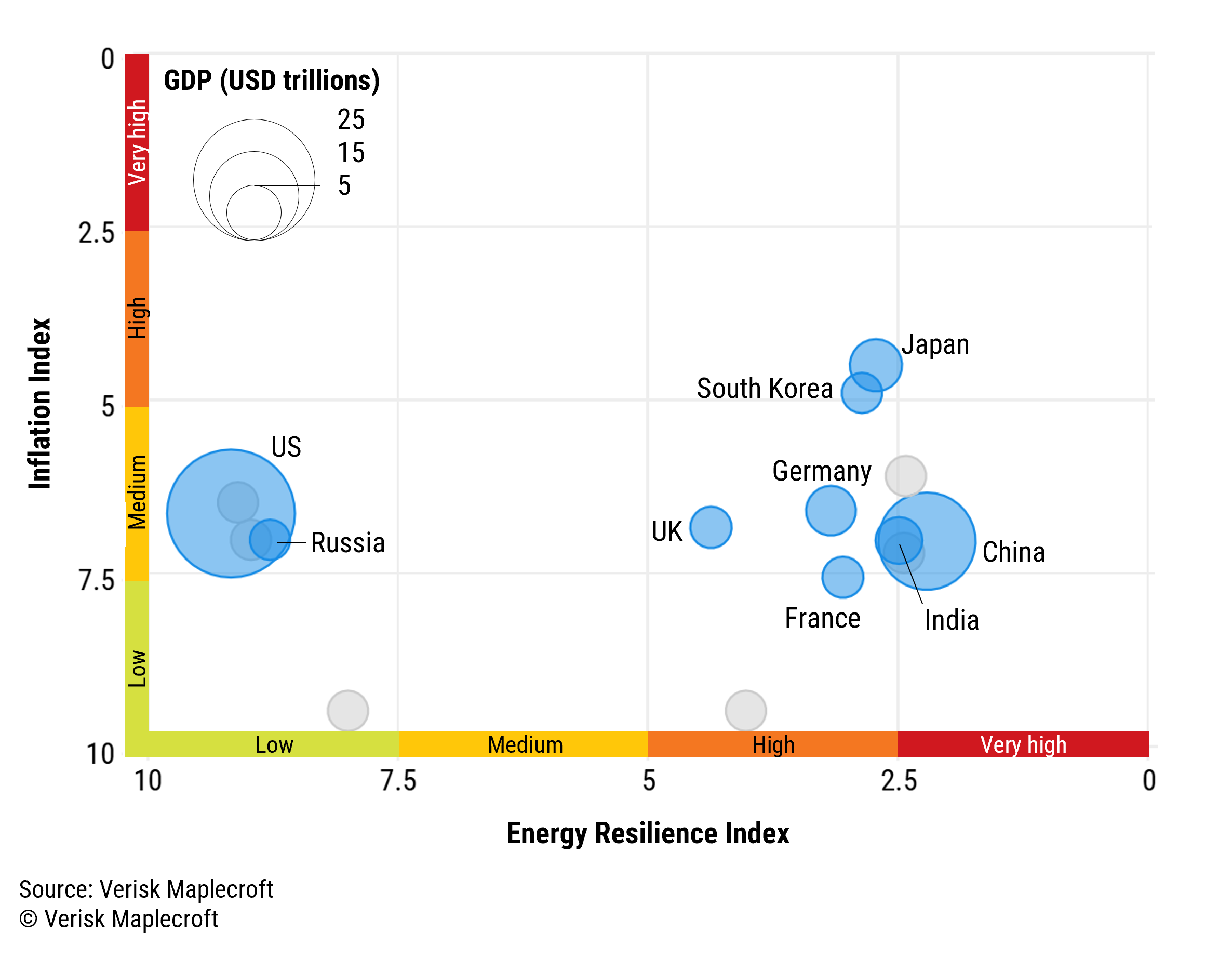

Destination concentration and a moderate price reaction should not be mistaken for energy resilience. For many major economies, the core vulnerability lies not in spot prices but in structural exposure to external supply shocks. As shown in Figure 2, the top Asian economies, alongside their European counterparts, face high-to-very high risks in terms of energy availability and continuity, often due to limited domestic production and undiversified consumption patterns. These risks are amplified by medium-to-high inflation sensitivity in many of these economies, increasing the likelihood of a disruption triggering broader macroeconomic instability. Top importers, including China, India, Japan and South Korea, are particularly vulnerable to geopolitical disruptions—even those that do not manifest in full-scale supply cuts.

Top global economies have been increasingly adjusting their energy strategies to be more geopolitics focused. The Ukraine war had already triggered a move toward energy security and diversification. The EU is phasing out Russian energy despite higher costs and tighter markets. China is strengthening energy ties with Russia to reduce Western dependence. Japan and South Korea are pursuing long-term Qatari LNG deals for supply stability, despite higher prices than the spot market. The latest Middle East escalation reinforces this shift: energy policy is now shaped as much by geopolitical risk as by price.

The limits of diversification

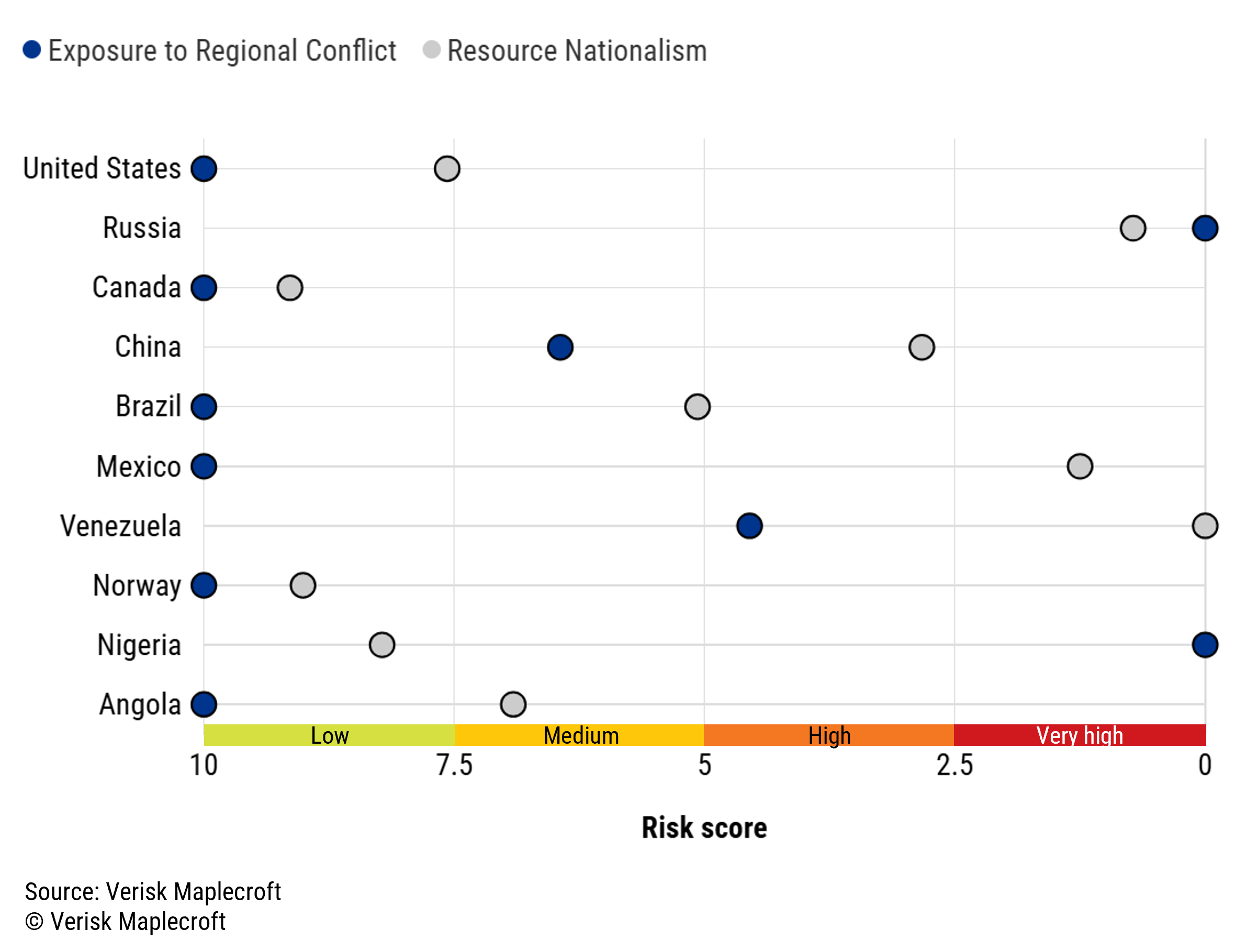

While Asian countries aim to diversify away from the geopolitical risks of the Middle East—where Gulf producers account for about one-third of global oil output—low-risk options beyond the region remain limited. The challenge is not just in securing energy supplies, but also in identifying politically stable jurisdictions with room for upstream expansion. As shown in Figure 3, only a handful of non-Middle East producers—such as Canada, the US and Norway—score low risk on both our Resource Nationalism Index and Exposure to Regional Conflict Index. This underscores the reality that diversification efforts remain vulnerable to shifting regulations and regional instability.

The latest conflict in the Middle East adds to a growing set of geopolitical pressures that are reshaping global energy planning. Energy strategy is shifting away from merely price optimisation toward risk management. Governments are prioritising politically stable supply routes, locking in long-term contracts and seeking greater control over strategic resources. However, diversification options outside the Middle East remain narrow. As a result, geopolitical risk is no longer a temporary market disruptor—it is a lasting factor in how countries source, invest in, and manage their energy systems.