Xinjiang sanctions disrupt global apparel supply chain

by Sofia Nazalya,

The implications of the recent sanctions enacted by the Trump administration targeting the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) have reverberated across global supply chains, with the apparel industry being the hardest hit. The XPCC, a paramilitary organisation, is one of China’s largest cotton producers, running large-scale agricultural farms and other businesses in the Xinjiang region that have long been tainted by forced labour allegations.

Although global brands will now look to alternative suppliers, completely disassociating from Chinese cotton is unfeasible given China’s sizable stake in global production. In addition, the sanctions are likely to cast doubt on existing due diligence processes that deem operations in Xinjiang to be compliant with sustainability standards.

Xinjiang cotton industry disrupted, but China will remain important

The sanctions ban all US entities or non-US entities subject to US jurisdiction from directly or indirectly engaging with the XPCC. Nevertheless, despite the impact the sanctions will have on the Chinese economy, Beijing will not budge on its position towards the region.

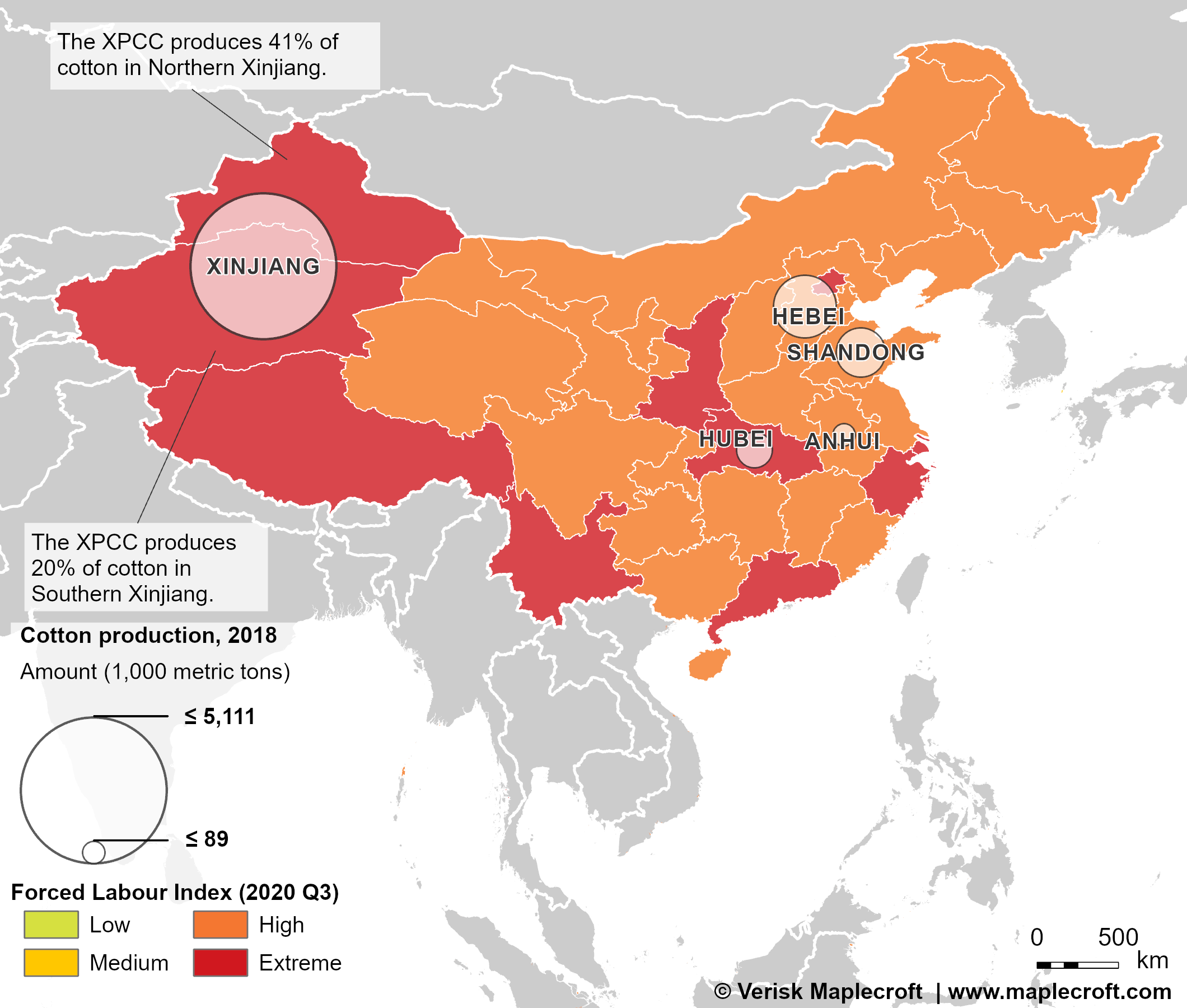

Seeking alternative suppliers will be no easy feat for the global apparel industry given the dominant role played by the XPCC in cotton production in Xinjiang. Based on available official data, in 2017 the XPCC was responsible for the production of 41% of cotton in northern Xinjiang and 20% in southern Xinjiang. Although it is possible to source non-XPCC produced cotton in Xinjiang, the risks of association to forced labour in the region remain extreme, as can be seen in our subnational Forced Labour index (see figure below).

Learn more about our commodity risk service

Given that Xinjiang is responsible for the bulk of cotton production in China – official statistics pointed to 85% in 2019 – the apparel industry will therefore find it challenging to disassociate its supply chains from the region completely. Moreover, our subnational scores also show that forced labour risks in regions outside Xinjiang are high or extreme regardless. We expect the situation to be much the same in the next two to three years, with the region continuing to record the highest risk of forced labour in China.

Similarly, it will be difficult for the industry to completely disassociate supply chains from China, given that it is the leading producer of cotton responsible for 30% of global output. The challenge to reduce reliance on the Chinese supply chain goes beyond the growing of cotton. China accounts for 50% of global exports of woven cotton fabric. For example, three-quarters of all cotton produced in Australia in 2020 was bought by Chinese mills.

Move to other suppliers may not improve corporate ESG profile

While it may be difficult for companies to completely disassociate Xinjiang from its supply chains, the sanctions have effectively tainted commodities made in the region with their association to forced labour. Many businesses are unlikely to want to shoulder any reputational or potential legal burdens and may begin to turn elsewhere to source its commodities.

Although our commodity data shows that China records the second-worst score for forced labour in the production of cotton, behind only Turkmenistan, major retail brands will not necessarily improve their ESG profiles by turning away from Chinese cotton. India, the second largest producer, similarly records an extreme risk score for forced labour in the production of the commodity.

The operational costs of uprooting suppliers and shifting operations to move away from XPCC-made cotton and other commodities are sizable and will certainly undermine profit margins. Beyond cotton, XPCC’s dominance in Xinjiang’s agriculture will impact the food manufacturing industry as well. Reports suggesting that the XPCC exports 17% of the world’s ketchup is a glimpse into the breadth of the organisation’s business activity. The organisation’s links to logistics, tourism, real estate and construction will mean that multiple global industries are similarly affected by the sanctions.

Labour rights unravelling as Asia’s garment sector comes apart at the seams

Read more nowTraditional due diligence may no longer make the cut

The sanctions call into question current due diligence methods that consider operations in Xinjiang to be sufficient. Significantly, it points to the massive challenges within the global garment manufacturing and apparel industry in addressing human rights violations in the supply chain. Particularly when operating in secretive jurisdictions where information is tightly controlled – such as China, and even more so in Xinjiang – the traditional processes of conducting due diligence may no longer be appropriate.

Ongoing pandemic related disruptions have also exacerbated the risks the sector faces, particularly to forced labour and other labour rights violations. Given the multitude of problems, companies must find a way to bridge the pandemic auditing gap. While more companies turn to remote audits during the pandemic, we do not expect this methodology to be particularly effective in monitoring working conditions in high or extreme risk jurisdictions – particularly in a tightly controlled region such as Xinjiang.