Why human rights in supply chains are a growing concern

Verisk Perspectives

by Victoria Gama,

The impact that the COVID-19 outbreak has had on poor and developing countries has placed the issue of human rights in supply chains in sharp relief.

Several countries in the Americas, Asia, and Africa already rank as extreme and high-risk in our Informal Workforce Index. With local businesses around the world poised to make cost cuts in response to the pandemic, the pool of informal workers may now grow and be more vulnerable to labour rights violations, potentially implicating different companies that source from these countries.

What is the Informal Workforce Index?

The Informal Workforce Index estimates the percentage of workers employed informally in each country. Workers employed informally are often the most at risk from a wide range of labour rights violations as they generally lack the legal protections and state oversight typically associated with formal employment.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), "informal economy workers often work in the most hazardous jobs, conditions, and circumstances across all economic sectors–agriculture, industry, and services. Typically, informal sector units are small-scale, engaging mainly non-waged and unorganised workers in precarious work processes and labour arrangements, largely unregulated and unregistered, falling outside state regulations and control, including those related to [health and safety] and social protection. The necessary awareness, technical means, and resources to implement [health and safety] measures are also lacking."

The ILO's latest report on informal work estimates that more than 61 percent of the world's employed population, i.e., some two billion people," earn their livelihoods in the informal sector. "In fact, of the two billion workers in the informal economy worldwide, 800 million are said to be women from predominately low-income countries who" are more often found to be the most vulnerable."

Even before COVID-19, developed countries recognised these violations as a major international problem and began enacting regulations to deter corporations from participating in supply chains that involve human rights violations. And according to a 2020 study by the European Commission and various other independent studies conducted by local NGOs, even when mandatory reporting human rights legislation is in place, some businesses fail to provide detailed reports over potential human rights impacts of their operations and actions taken to remediate them.

To help mitigate this issue, governments, primarily in western Europe, Canada, and the United States, are looking to heighten business human rights obligations by making supply chain human rights due diligence mandatory—with stricter obligations, heightened sanctions, and enforcement bodies with robust mandates along the lines of the French Duty of Vigilance Law and the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Law.

Perhaps recognising that the societal and economic trends inflicted by COVID-19 may threaten years of progress on this front, the private sector also has undertaken efforts to address human rights issues. For example, in April 2020, a group of 101 international investors representing over $4.2 trillion in assets issued a joint call for greater regulatory measures requiring companies to carry out human rights due diligence.

Download the full Verisk Perspectives report now

Could a combination of regulations and an increased emphasis on responsible sourcing help blunt the potential adverse impacts caused by COVID-19? It will likely be a difficult road, given human rights violations often transpire in supply chains that yield products that are not only in high demand but also socially beneficial. Two examples help underscore this point: 1) the sourcing of a vital component to manufacture hand sanitiser and 2) the mining of elements and other materials that make zero-emission electric vehicles (EVs) possible. If more laws are enacted to impose liability on corporations that participate in a supply chain with human rights violations, there could be repercussions relating to the production of both of these goods.

An upsurge in hand hygiene may pose high human rights risks

Alongside masks, hand sanitiser has become a viable weapon in the battle against COVID-19. But the supply chain behind alcohol-based hand sanitiser (and its main ingredient, ethanol) runs through countries with a notorious human rights track record that includes forced labour and child labour.

The harvesting of sugarcane, from which ethanol is derived, is typically done by hand and is extremely physically demanding, involving a large number of repetitive movements. Take Brazil, a major producer of sugarcane. According to a 2006 study, a Brazilian worker cutting 12 tons a day will walk an average of 8.8 kilometres/5.5 miles per day and perform over 130,000 cutting motions. Evidence of low salaries–barely higher than the minimum wage–and the use of the 'champion system' in which workers are paid based on the amount of sugarcane they collect, compel workers to dedicate extra hours in intense heat, according to the study. Some workers labour for 10 to 12 hours a day.

Added to that, occupational health and safety issues due to the lack of personal protective equipment can make workers prone to machete-related injuries and respiratory problems resulting from burning cane; this dynamic could explain the extreme or high-risk scores seen in our Forced Labour Index.

In Brazil's case, the use of forced labour resulting from an increase in sugarcane demand to distill alcohol for hand sanitisers is hardly unprecedented.

Public Prosecutor's Office (Brazil) investigations resulted in more than 10,000 people being reportedly freed from forced labour on sugarcane plantations between 2003-2011, while 2013 statistics show that from 2003-2013, sugarcane accounted for the second-highest number of forced labour reports.

Despite these enforcement actions, in 2018, the United States Department of Labor highlighted sugarcane sourced from Brazil as having a high risk of being produced with forced labour due to the frequent practice of debt bondage. Although the Brazilian government attempted to address the issue, its release of the 2019-H1 lista suja or 'dirty list,' which names and shames companies for the use of forced labour, included numerous sugarcane farms.

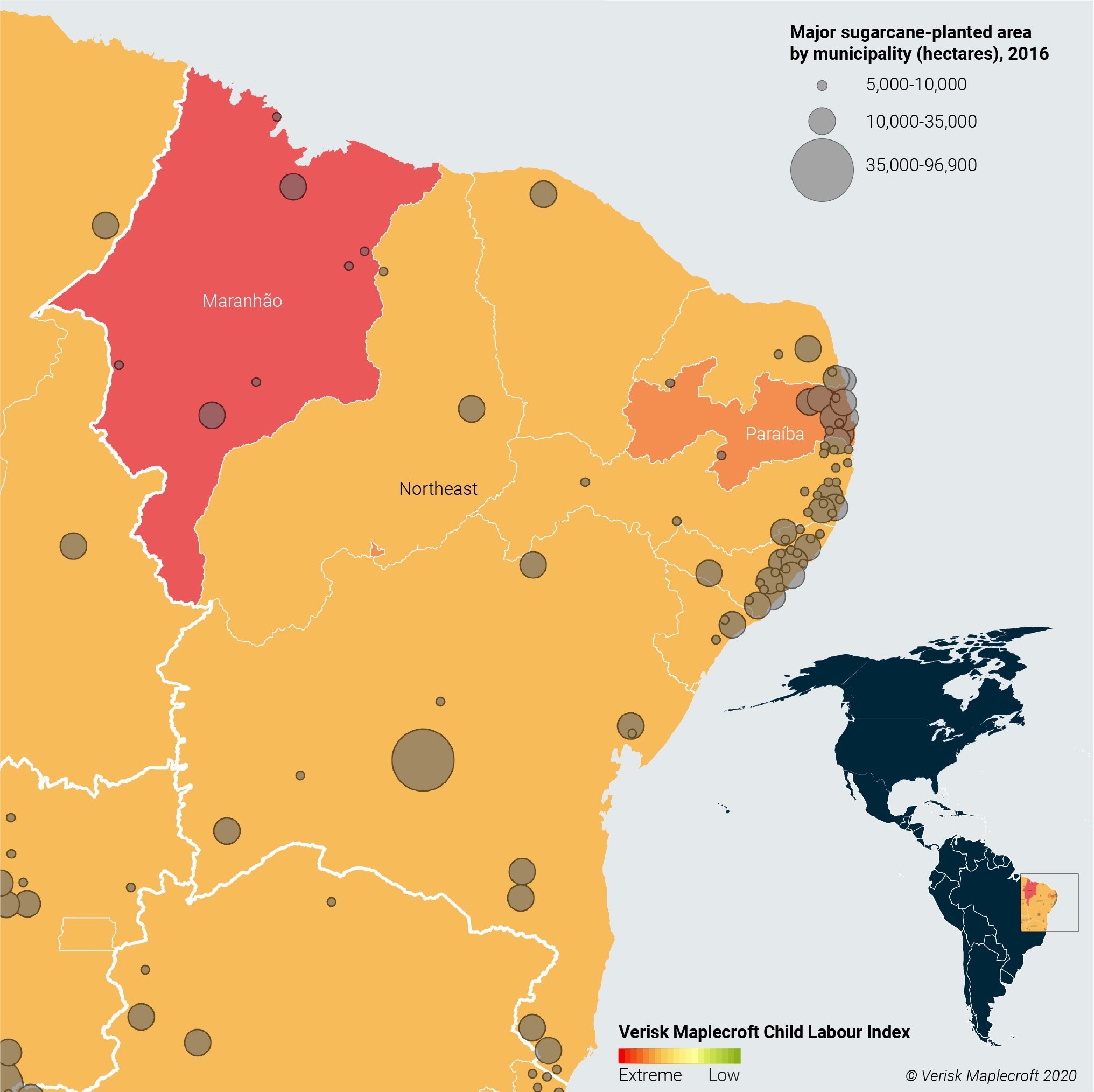

It's worth considering that there are significant differences between southern Brazilian states, such as São Paulo, where mechanisation prevails, and the northeastern states, where the harvest is still done manually. In the map, you can see our subnational forced labour index that highlights the disparities between the risks of forced labour in the Northeast and Southeast regions, a critical example being Maranhão, where manual intensive sugarcane harvesting still prevails.

While mechanisation of the sugar industry is credited with reducing the number of forced labour incidences in those areas, labour standards vary significantly by region.

Even with more stringent human rights regulations being passed in wealthier countries, we don't anticipate a reduction of instances of forced labour, as the labour inspectorate's funding reportedly has been reduced under Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro's administration. According to the Federal Budget Secretary, in 2019, the allocated budget for labour inspections decreased by 60 percent year on year to BRL3.3 million (USD 785,732). Furthermore, Brazil only has 2,997 inspectors – 29 percent of the number it requires under the ILO benchmark – leaving the promotion of decent working conditions largely down to businesses and trade unions.

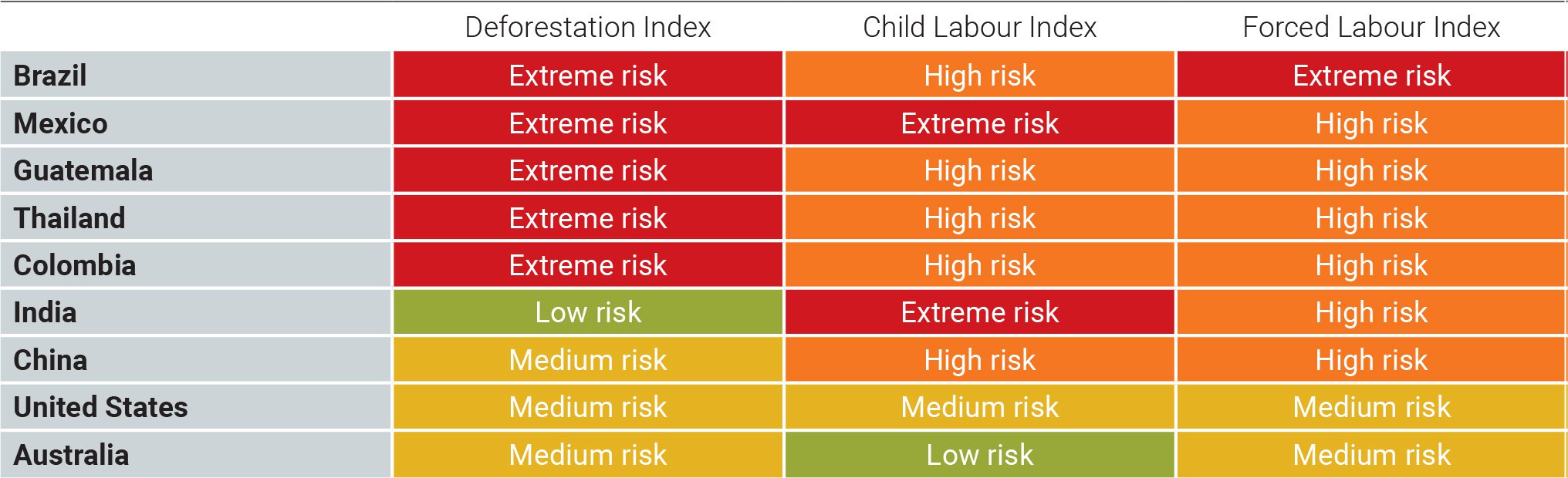

According to new data from our Commodity Risk Service, the production of sugarcane already poses a high or extreme risk of child labour, modern slavery, and deforestation in countries such as Brazil, India, Mexico, and Thailand. And the situation is likely to worsen as the COVID-19 economic fallout makes its way through these countries, and demand for sanitiser remains high.

Electric vehicles: a greener approach can come with a high human price tag

The economic disruptions caused by COVID-19 have highlighted the risks posed by the United States and Europe's extreme reliance on Asian-based supply chains to cater to their domestic market and decarbonise their economies. This recognition has appeared to encourage governments on both sides of the Atlantic to rethink their dependence on global supply chains for EV production as they seek to revitalise their battered economies.

Although bringing production of EVs home might reduce labour rights violations in the production and assembly of those vehicles, both Europe and the United States could still heavily rely on battery raw materials sourced from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Chile, and Argentina in the years to come. All three regions have problematic records concerning human rights and mineral extraction.

Our subnational Child Labour Index and Security Forces Human Rights Index point to higher risks for cobalt extracted in the Haut Katanga and Lualaba provinces of the DRC, demonstrating the hazardous conditions in which children work in illegal mines to extract minerals.

Child labour is widespread throughout the DRC's cobalt supply chain, but occurs mainly in artisanal mining, a traditional mining form where miners are not officially employed by a mining company but normally sell minerals to them. An estimated 30 percent of DRC's total cobalt production is carried out by artisanal miners, which leaks into industrial mining supply chains. In December 2019, Apple, Google, Microsoft, Dell, and Tesla were accused before a U.S. court of allegedly aiding and abetting in the death and serious injury of children working in cobalt mines associated with their supply chains.

The high and extreme risks scores for Chile and Argentina in our Indigenous Peoples' Rights Index illustrate the underlying tensions between the expansion of production of minerals required in EVs and the demand for compliance with the United Nation's free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) processes from indigenous communities.

FPIC is a specific right that indigenous peoples have, which allows them to give or withhold consent to a project that may affect them or their territories. According to this right, states have to consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior, and informed consent to any resource extraction project on their territory.

Read more on conducting Human rights due diligence

The so-called "Lithium Triangle" in Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina, where an estimated 75 percent of the world's lithium is located, has been an arena for litigation. One such example is in Chile, where a local court upheld a water usage complaint from the Camar and Peine indigenous communities who were not consulted over the expansion of SQM’s mine in a water-scarce area.

In 2010, 33 indigenous communities from the Great Salt Mines and the Guayatayoc lake located in the northern provinces of Salta and Jujuy, Argentina, took their FPIC case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which is reportedly known for its extensive pro-FPIC jurisprudence. Though litigation can be time-consuming, we expect these lawsuits to shape reform conversation and produce a lasting impact.

Accountability may be coming for businesses of all sizes

These two examples are just a glimpse of current human rights scenarios in supply chains and how a post-COVID-19 world can exacerbate already fragile human rights environments. With regulatory bodies paying increasing attention to these issues, coupled with growing expectations of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and sustainability for corporations, human rights due diligence is becoming imperative for companies to avoid related reputational, operational, and litigation costs.

Corporate human rights due diligence is slowly becoming a norm of expected conduct for all types of businesses no matter the size or sectors, and businesses are joining governments by asking for a clear and more transparent playing field. Given this dynamic, more businesses in the European Union are endorsing the EU’s proposal for a single, all-encompassing law that would eliminate the need to navigate a patchwork of potentially juxtaposing legislation.

These regulations could cast a wider net over the entire corporate structure, as well as their business relationships. For now, the expectation is that due diligence will reach Tier 1 of the supply chain – the companies that deliver product devices that are almost close to the finished product – but obligations will likely progressively be cascaded down value chains through business-to-business pressure. No matter what form the ultimate regulations take, the trend seems clear: the era of voluntary compliance with human rights supply chain initiatives is ending. In its place, we can expect a more forceful regime of sanctions, monitoring, grievance mechanisms, civil liability, and extraterritorial litigation.

Verisk Perspectives

This insight first appeared as part of Verisk Perspectives, an ISO Emerging Issues report. Download the full report here.