The January drone strike in Baghdad – which killed Major General Qassem Soleimani, head of Iran’s military operations abroad, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the Iraqi leader of pro- Iranian militia group Kata’ib Hizbullah – was the clearest signal yet of a new US relationship with the Middle East.

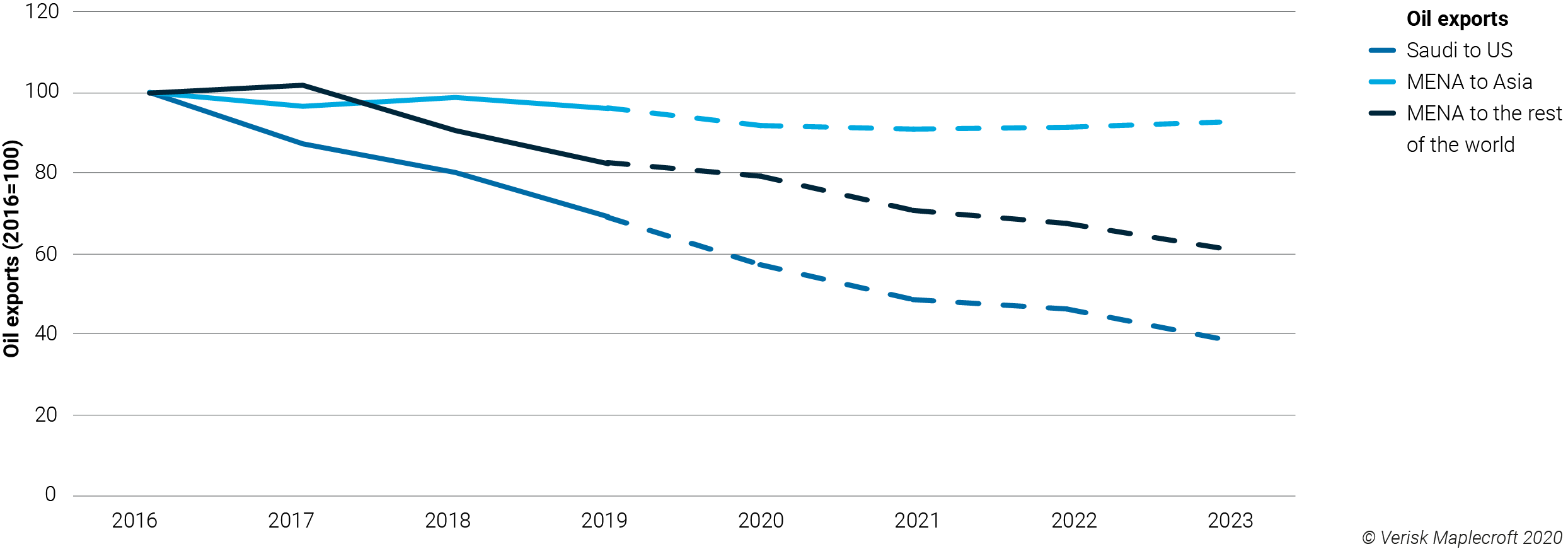

While the Baghdad strike showed that the world’s largest military power continues to flex its muscles, America’s policies towards the region are changing. As US shale oil production has increased, and with Middle East oil exports to Asia now higher than to anywhere else globally (see Figure 1), the role of the United States in guaranteeing security in the region as a quid-pro-quo for secure energy supplies has weakened.

‘Bring our troops home’ was a powerful rallying cry during President Trump’s first election campaign, but personnel numbers in the region remain the same as under Obama. So, the capabilities are still there. But the willingness of the US to step in and defend its traditional partners in the Middle East has receded in line with its diminishing reliance on Saudi oil, and we believe this could preface more insecurity in the region.

For oil exporters like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the prospect of a dwindling role played by the US raises fears of a security vacuum. Without robust security in the Persian Gulf, the Gulf economies and 20% of the world’s oil demand are under threat. But Washington is increasingly unwilling to underwrite protection for oil production and shipping that is of most benefit to its biggest geostrategic rival, China. The absence of a forceful public response from the Trump administration following the May and September 2019 attacks on oil tankers and installations in Saudi Arabia show that the threshold for the US to act in the region is much higher than in the past.

Download the Political Risk Outlook 2020

Direct conflict risks low, but anxieties run high

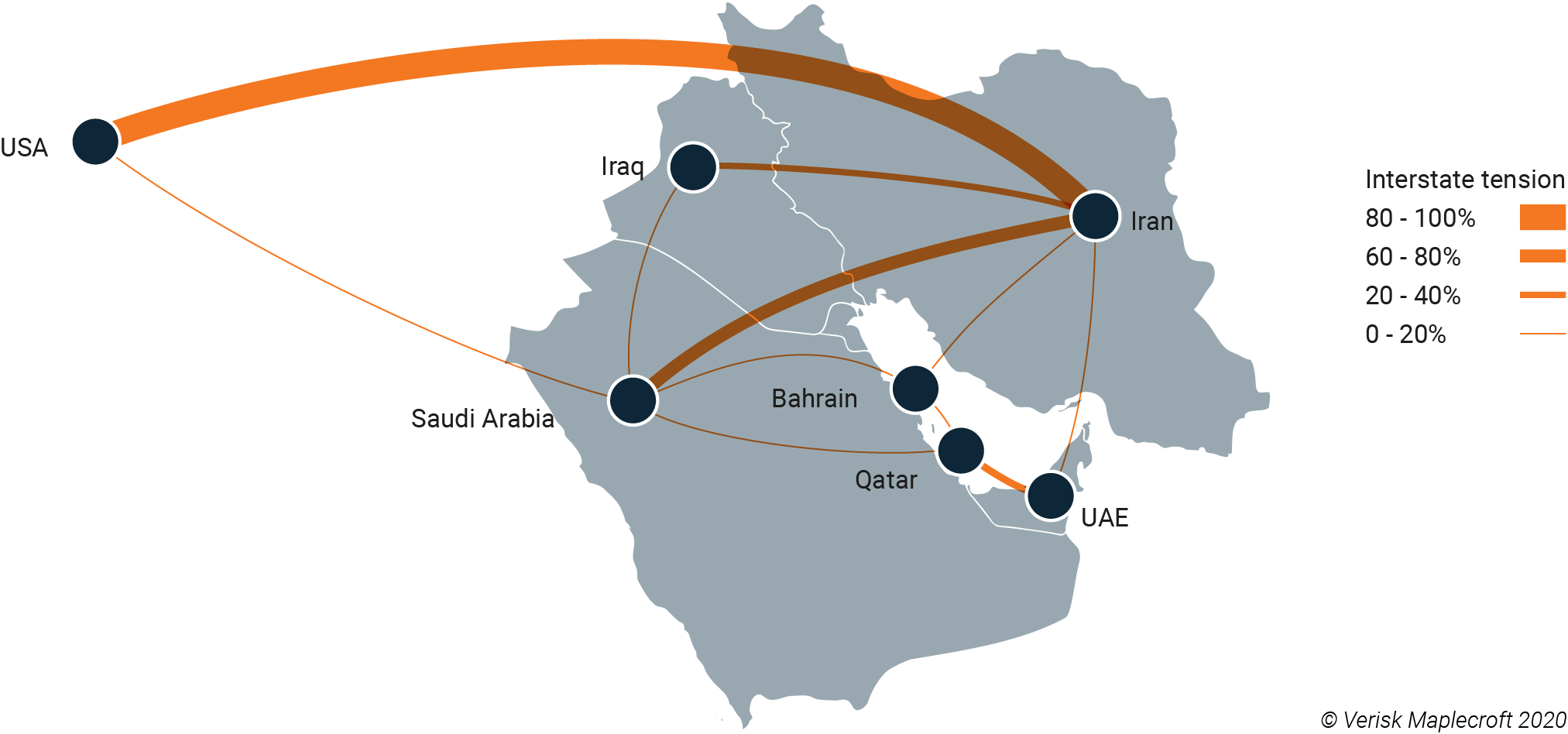

The exchange of missiles at the opening of 2020 reinforced the uncertainty of this threshold, and raises the question: what are the chances of a major confrontation between Iran and the US? Our Interstate Conflict Model – which tracks historic verbal conflict, military spending, bilateral trade, regime type, and how these factors drive militarised conflict between countries – calculates the chances of the use of military force between the US and Iran to be 78%, and this was even before the Baghdad drone strike.

While this is a high probability, our analysts believe it is substantially mitigated by historical precedent and other factors such as domestic political issues.

Our judgement-based forecast assesses the likelihood of an Iranian fatality in Iranian territory or the Persian Gulf as a result of US military action to be 35%. With 2020 being an election year for both countries, it is in neither country’s interest to get into a protracted armed conflict.

Even though the risk of direct confrontation is relatively low, America’s closest allies in the Middle East are not willing to completely abandon their relationship. But they cannot read where the new threshold for US protection is. The question is whether the US presence in the Gulf will continue to effectively deter Iran from disrupting oil supplies when Tehran is being backed into a corner by the collapsing nuclear deal.

Market impact

The growing perception of intensifying risk in the Persian Gulf will be felt across a broad range of sectors from sovereign debt to petrochemicals. But the most direct impact will be felt in shipping, where security risk premiums for vessels travelling through the Strait of Hormuz have already increased as much as tenfold in recent months. Without a concrete and viable solution to the current impasse between Iran and the US, insurance premiums are likely to rise further through 2020.

Oil markets will also have to grapple with a growing Persian Gulf risk premium. Although it took merely two weeks for oil prices to fully recover after the attacks on the Abqaiq and Khurais oil-processing facilities in September 2019, there is a strong case that the risk of another high-impact attack is underestimated. With spikes in oil prices both then and after the Baghdad drone strike, the risk of more disruption and a concomitant rise in fuel prices has not been sufficiently priced in.

What if…the Iran nuclear deal doesn’t survive 2020?

This year will be a make-or-break year for the nuclear agreement between Iran and world powers. With Iran losing as much as USD4 billion in revenue every month due to US energy sanctions, it will not be easy for Tehran to hold out for the possibility of a new US president being elected in November 2020.

Even if a new US president takes office in January 2021, there are risks that the deal will collapse. First, Iran may decide to walk away from the agreement entirely in the face of a firm commitment by President Trump to the policy of sanctions. And second, if Iranian violations of the deal persist and increase in severity, the UK, Germany and France may no longer be able to keep the agreement alive.

A collapse of the deal would make an already dangerous regional climate even more volatile and unpredictable. If Iran resumes its pre-agreement nuclear programme, tensions with the US, Saudi Arabia and Israel will go from bad to worse.

Register for our Political Risk Outlook 2020 webinar