Coronavirus: EU travel restrictions could trigger green innovation but will otherwise undermine ESG & Human Rights

by Camilla Ogunbiyi and Filip Rambousek,

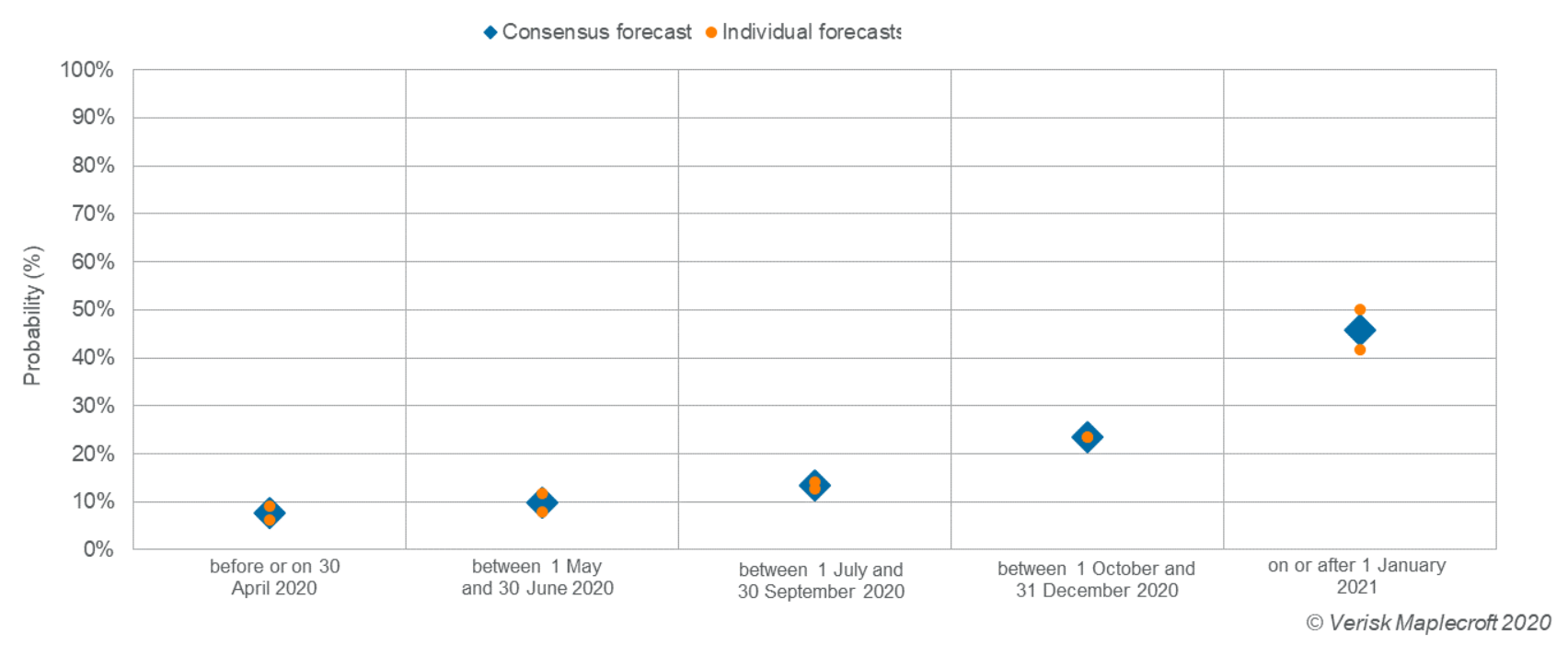

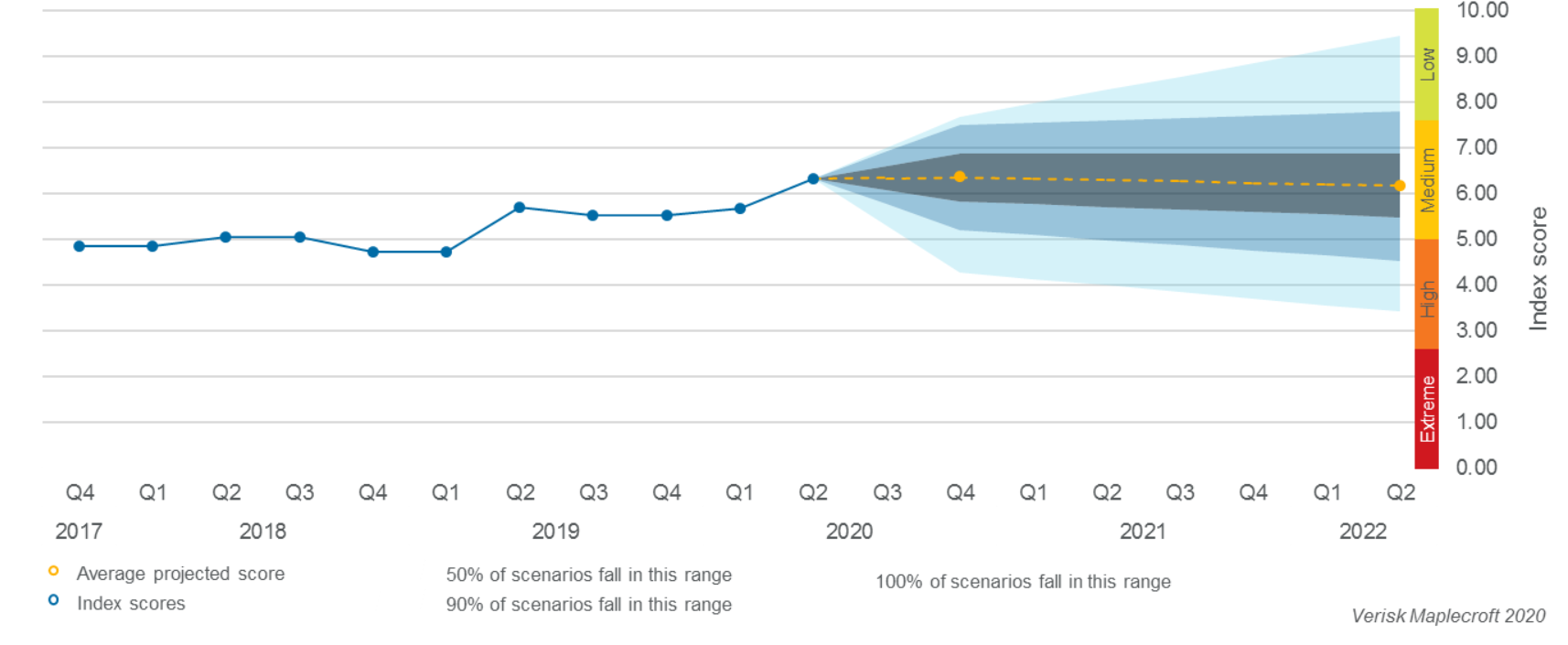

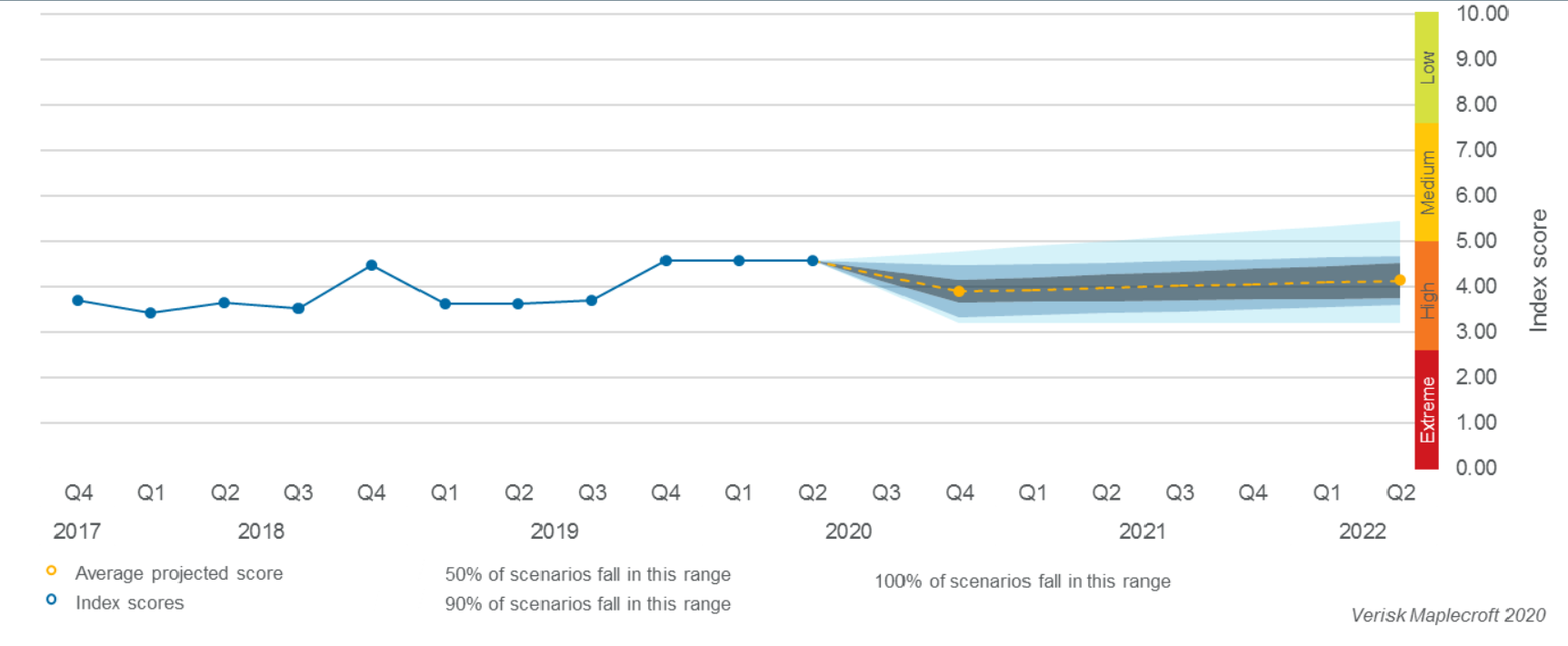

Travel restrictions in EU states are likely to remain in place for much, if not all of 2020. We forecast 46% probability that a majority of EU member states will still have entry restrictions in place at the national level at the start of 2021.

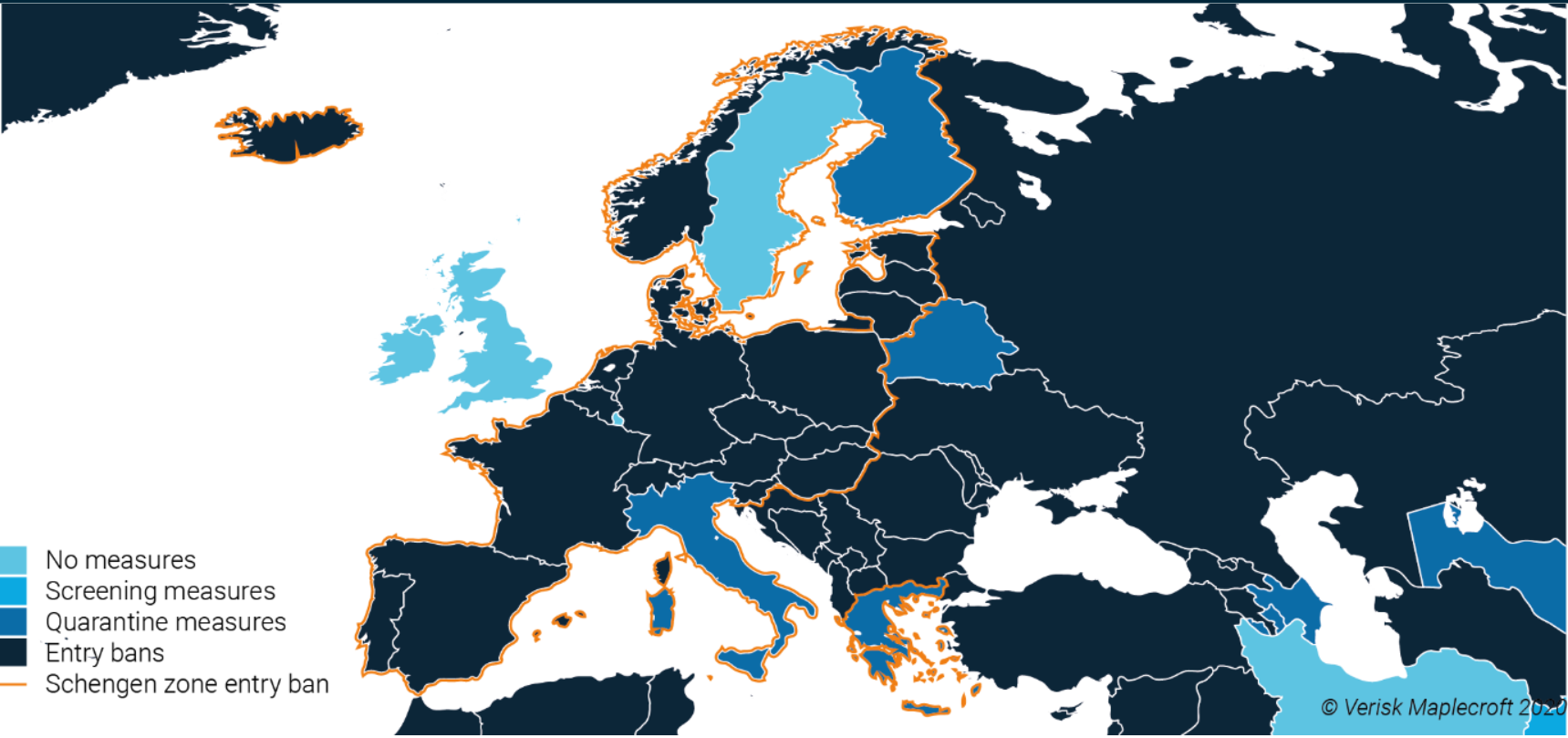

Europe’s agricultural sector relies on seasonal labour from migrant workers, primarily from central and eastern European states, to harvest crops. Travel restrictions have made it extremely difficult for farmers to source this labour, despite varying degrees of government assistance. As a result, despite their focus on restricting movement of people, travel restrictions are also disrupting supply chains across Europe caused by increased delays at border crossings and limited availability of seasonal labour.

The increased strain on logistics chains will disrupt food shipments. This will lead to price increases and shortages. We nevertheless see the potential for positive disruption from these challenges as well, for example, a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

The good: Innovation lessening carbon footprint of food supply chain

As food prices go up and certain goods fail to reach their traditional markets, innovation in foodstuffs will likely get a boost. Several European producers of lab-grown meat, which had been rolling out their prototypes before the crisis, now face a market that is likely more receptive than it would have been under ‘normal’ circumstances.

Companies are already seeking to make food supply chains shorter, more robust and remove reliance on cold storage middlemen. Refrigeration produces particularly potent greenhouse gasses (GHGs), and supply chain reconfiguration has the potential to greatly reduce the food sector’s ‘carbon footprint’. With the EU’s agricultural sector accounting for around 10% of total GHG emissions, this would result in a significant reduction in its overall emissions.

The bad: Social unrest risks driven by lockdowns, food price rises and unemployment

For the moment, lockdowns are keeping large sections of European economies shut down, and labour shortages are therefore not currently an issue. However, as lockdowns lift while borders remain shut, seasonal workers, the majority of which come from central, and eastern European states, will be prevented from travelling abroad.

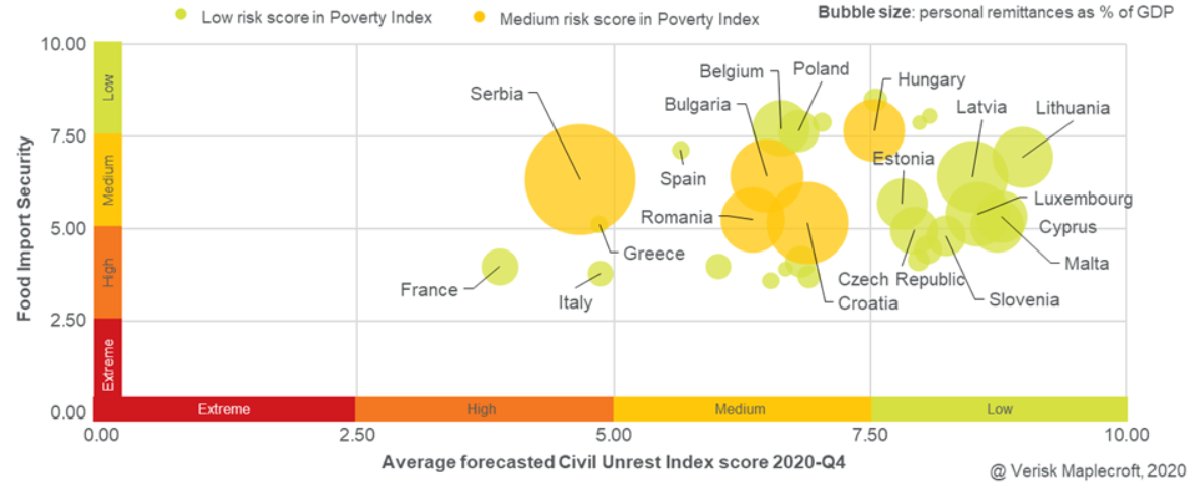

This will have knock on effects. Food prices and unemployment will rise, while social frustration will mount over border restrictions and a lack of income for informal and seasonal workers. These factors will drive up the risk of social unrest especially in central, southern and eastern Europe.

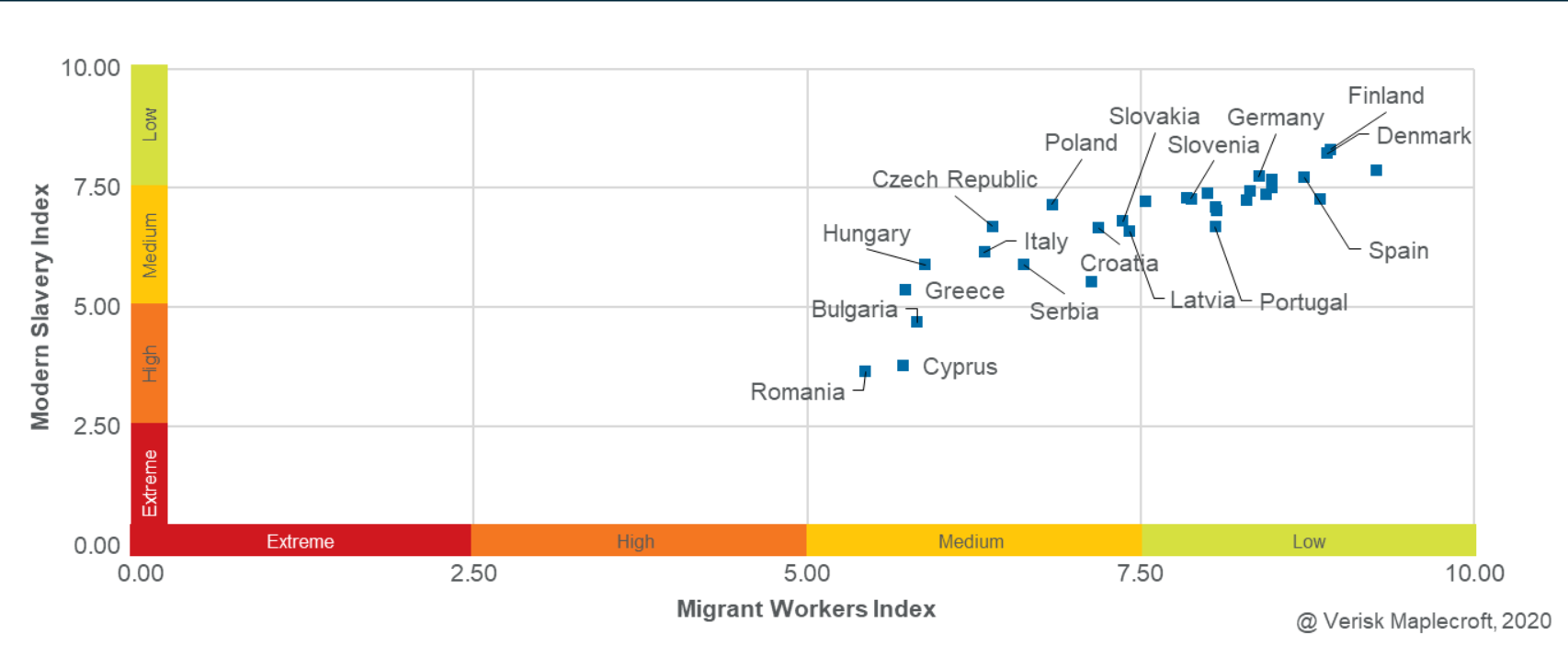

Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia and Hungary are among the poorest and most remittance-dependent countries in Europe (see figure below). With migrant workers now unable to travel for seasonal work, domestic unemployment will rise sharply, increasing the fiscal pressure on these economies.

We expect the risk of civil unrest to be especially pronounced in countries with poorly resourced healthcare systems such as Romania. As more people catch the virus, and the healthcare system is perceived to be failing to avoid preventable deaths, civil unrest is likely to rise.

While richer and less reliant on remittances, countries in western Europe will also be at increased risk of social unrest when lockdowns are lifted. In France, President Macron is currently benefiting from a ‘rally around the flag’ effect, boosting the support of his government. However, existing opposition to his reform programme is likely to resurface following the easing of domestic COVID-19 restrictions. Rising food prices will likely add fuel to the fire in France, a country highly reliant on food imports and with a strong culture of social unrest.

The ugly: Weakening of labour rights and increase in human trafficking

The imposition of states of emergency carries the risk that labour rights legislation will be weakened in European countries which depend on regular influxes of season workers. To address the lack of workers, European governments are likely to water down labour regulations, allowing for longer working hours. With governments in crisis management mode, enforcement of labour protections is less of a priority, increasing the risk of health and safety incidents and general labour right violations.

Countries which weaken their labour rights are likely to ignite higher rates of civil unrest. In late 2018, the Hungarian government introduced labour regulation reform, which increased legal overtimes from 250 to 400 hours per year. This amendment resulted in widespread civil unrest on the streets of Budapest. Such demonstrations of civil discontent are rare in Hungary and illustrate the potential that changes to labour regulation that are perceived to be against the interest of workers are likely to motivate civil unrest. Once implemented, such labour rights amendments may become politically and economically difficult to reverse.

Moreover, the combination of a high demand of seasonal workers in western Europe, combined with unemployment in eastern Europe, is likely to lead to an uptick in illegal border crossings, a widening of the grey labour market, which could potentially include human trafficking to satisfy the demand for labour. The extent to which this occurs is largely contingent on the severity of the border restrictions implemented by individual European states.

Conclusion

The long duration of border closures predicted in our forecast will provide ample time for businesses to reinvent their supply chains and drive food production innovation. This may have a variety of long-term benefits, most notably in cutting GHG emissions.

However, it is not clear that these long-term benefits will outweigh the more immediate ESG risks stemming from weaker labour rights enforcement, potential gross human rights violations and civil unrest.

Additionally, the long-term nature of the coronavirus outbreak also means that a potential drop in enforcement efforts of labour rights protections will potentially become a long-term feature of the European landscape.