Russian war in Ukraine reshapes APAC regional security and economic outlook

by Aditi Mittal and Joseph Parkes and Sofia Nazalya and Dr Kaho Yu,

The outbreak of the largest interstate war in Europe since the Second World War has profound implications for Asia. More than a month after the conflict began, its impact on Asian populations, governments and the regional security landscape is becoming clearer. We highlight the trajectory of China-Russia relations and Russia’s energy exports to Asia, the need for reassurance over US commitment to upholding the regional security balance, and the region’s exposure to food price spikes as key issues to watch.

As Western sanctions bite, Russia pivots to the east

Escalating tensions with the West and crippling economic sanctions are speeding up Russia’s ‘pivot to the east’, creating more business opportunities for Asia. In particular, China is becoming more important in Russia’s export portfolio, with European demand for Russia’s resource commodities fading in the long term. Meanwhile, to avoid over-dependency on China, Russia has simultaneously been trying to advance its commodity export to other Asian markets, such as India.

Western companies divesting from Russia means that Asian companies will likely face fewer competitors in the Russian commodity market, giving them the upper hand in the negotiation of terms and prices. Asian companies with a high-risk appetite will fill the market vacuum in Russia after other international investors leave due to sanctions.

More imports from Russia will help Asian countries diversify sources of supply further to boost their energy security. Major importers such as China and India will be in a more comfortable position to negotiate terms with other energy suppliers.

While major importers will likely continue regular trade with Russia, companies taking over interests in Russia will be under the spotlight of US and EU authorities. Asia’s major importers will have to ensure they are not stepping on the red lines drawn by the US and the EU, otherwise they risk being targeted by secondary sanctions.

Read more about our Country Risk Intelligence service

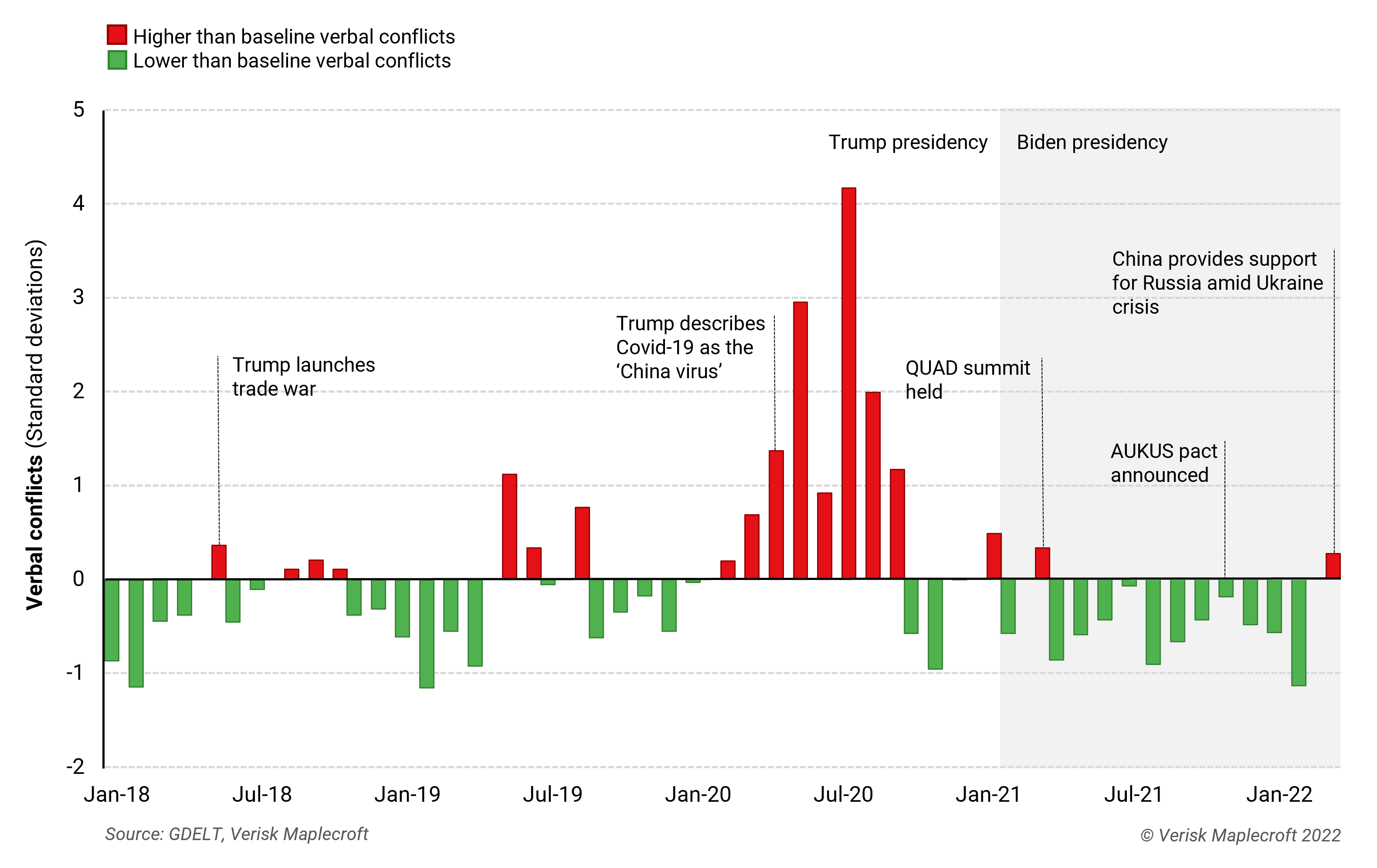

Support for Russia becomes another friction point in China-West relations

Beijing has maintained its close political and economic ties with Moscow, even while the war in Ukraine has tested the strength of the China-Russia partnership. Russia remains important to Beijing’s strategic interests because China does not want to face the US alone. Beijing’s top priority is still its strategic confrontation with the US, where Russia is a useful long-term ally.

Although it is an unbalanced relationship of convenience, China and Russia are set to remain strategically interdependent in the long term as long as they share the same rivals—the US and its Western allies. They will increasingly rely on each other as a source of leverage against the West. After all, the enemy of an enemy is a friend.

However, China is unlikely to burden itself by attempting to carry Russia’s strained economy. It is instead in a favourable position to take advantage of Russia’s reliance on the Chinese market while being cautious about its own exposure to secondary sanctions.

China’s stubborn support for Russia has become a new friction point alongside Xinjiang, Taiwan and Hong Kong in its long list of disputes with the US and the EU. In their high-stakes meetings with Chinese President Xi, US President Biden and EU President von der Leyen tried to press China to cooperate in pressuring Russia and warned China about secondary sanctions. Although President Xi agreed to manage their differences more effectively and reduce the potential for crisis, he also highlighted that the China-West divergence will remain.

Russian invasion a geopolitical shock for US-aligned APAC states

Developments in Eastern Europe are prompting reflection in APAC, another region where the credibility of US alliances, resolve and the nuclear umbrella are central to strategic calculations. Governments across APAC, including Beijing, are parsing the Ukraine conflict for geopolitical lessons.

Beijing is now Washington’s key strategic rival, but Russian revanchism makes clear that the European theatre is far from settled. With war on NATO’s doorstep, Russia has temporarily reclaimed its position at the top of the US security agenda. Washington’s perennial challenge of splitting its attention and resources between Europe and Asia is only getting harder.

The scenario that would prompt the most sleepless nights in Washington would be if Moscow and Beijing coordinated their provocations to maximise the strain on US capacity. So far, Beijing’s support for Moscow has been cautious, with no overt action taken to capitalise on a potentially distracted US. But as Moscow and Beijing move closer together in the wake of Western sanctions, APAC governments will be on the lookout for signals of US resolve to meet future challenges from China.

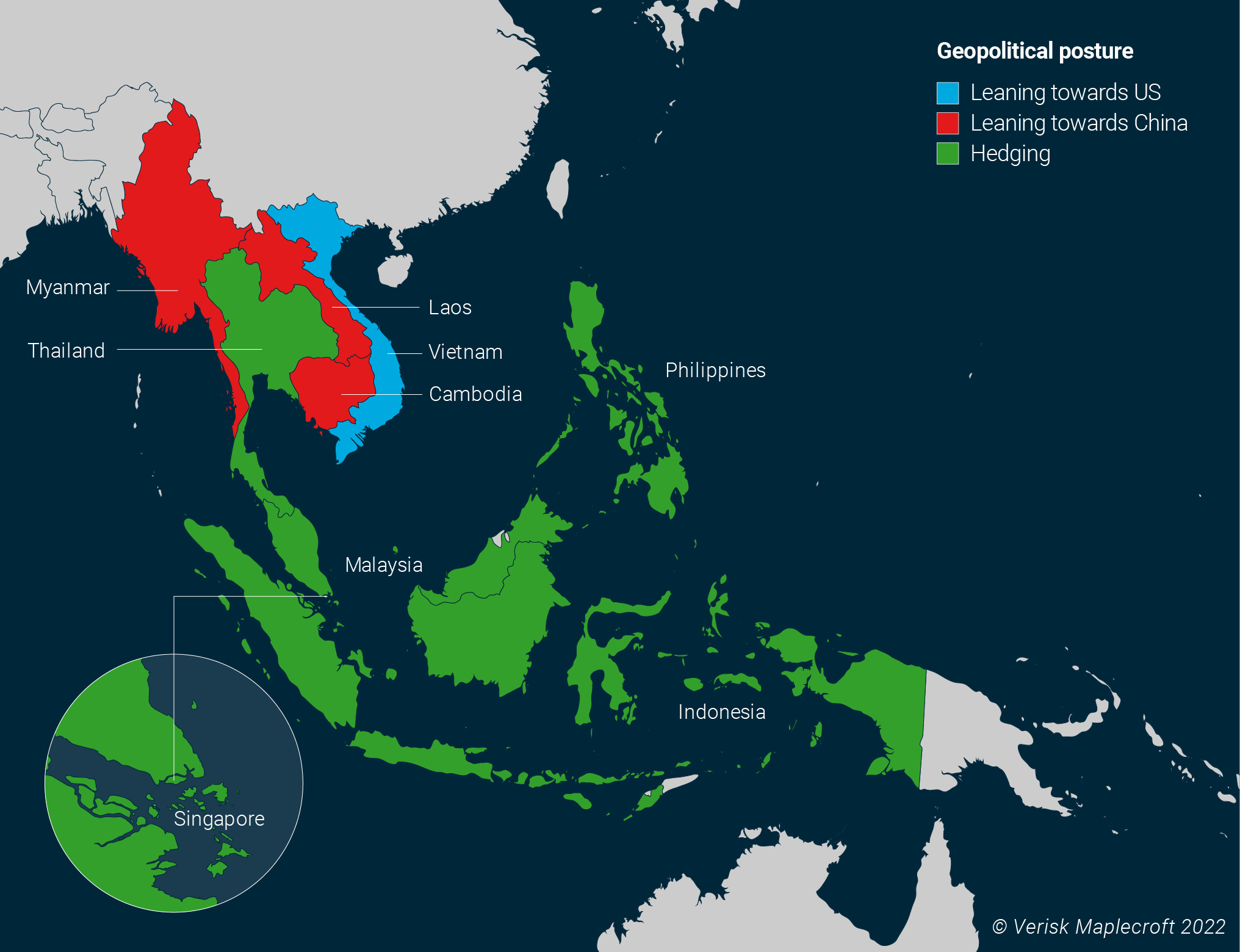

Indeed, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has called for the US to end its policy of strategic ambiguity over whether it would intervene militarily to defend Taiwan, and for Japan to consider hosting American nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, the US has work to do to boost relations with ASEAN after a rocky year. The next US-ASEAN summit, at which Chinese aggression in the South China Sea will feature prominently, will be one to watch. The map below provides the collective assessment of our Asia Risk Insight team of whether ASEAN states are currently ‘aligning with the US’, ‘aligning with China’ or ‘hedging their bets’.

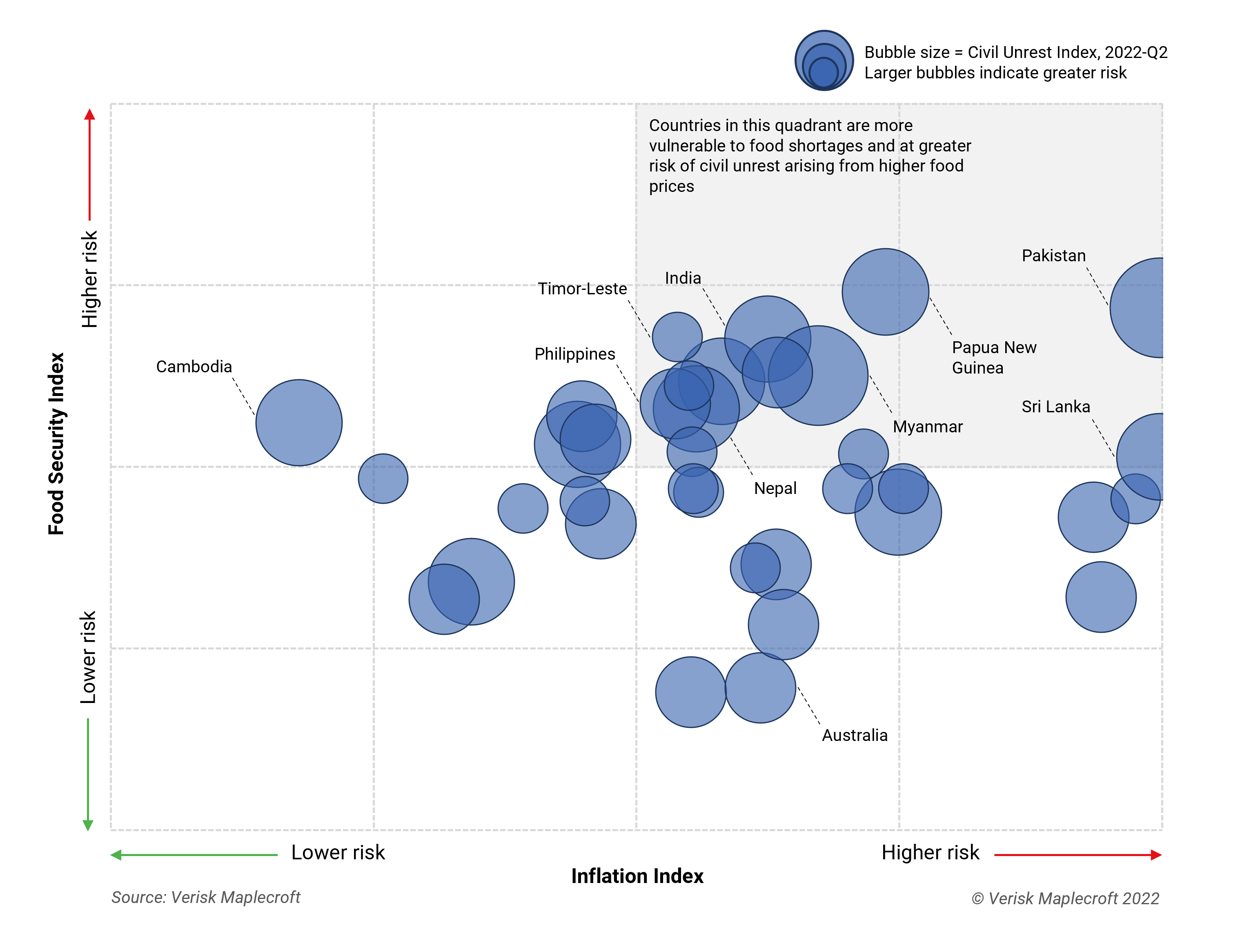

South Asia and the Pacific Islands are at higher risk of food insecurity

The Russia-Ukraine war is disrupting the global food trade, driving up food prices, which were already at 10-year highs in January 2022 because of the pick-up in demand amid COVID-19 recovery. Russia and Ukraine supply one-third of global cereal exports, including wheat, maize, and barley, and 50% of the world’s sunflower oil. The reliance of some Asian countries on grains and edible oils from these two countries has left them scrambling for alternate suppliers while diversifying their food baskets. This trend will likely have a spillover effect on other food commodities like rice, palm oil, rapeseed oil and soy.

Moreover, Russia’s ban on fertiliser exports and sanctions on Belarus have reduced the global supply of critical fertilisers, including potash, urea and nitrogen, by 20%, threatening global crop yields for the next year. Further, China’s export restrictions on phosphates combined with logistical disruption faced by Canada’s fertiliser industry signal a tight supply for the next 3-4 months. Higher input costs will likely curtail food production and reduce low-income countries’ purchasing power.

The net effect of high food inflation and undersupply of fertilisers will be a shortfall in food availability in many countries. As seen in the chart below, most South Asian and Pacific countries are categorised as high risk on our Food Security and Inflation Indices for 2022-Q2, making them particularly vulnerable to food insecurity. Many of these countries are also at higher risk on our Civil Unrest Index, 2022-Q2.

Public discontent arising from persistent high food prices increases the risk of civil unrest and political instability, primarily in countries that face wider economic distress. These effects are already apparent in Sri Lanka and Pakistan, which stand knee-deep in political turmoil. Myanmar and Nepal, facing imminent economic crises, are also at greater risk of social unrest. Rising palm oil and soybean prices are also likely to result in union-led protests in Indonesia.

Governments will likely follow with protectionist measures to ensure domestic food security, which risks unintended consequences. For example, stockpiling will likely fuel global supply shortages, creating an inflationary spiral. Food and fertiliser subsidies will possibly alleviate hunger but overwhelm budget deficits. Such pressures are likely to be met with tighter monetary policy, delaying economic recovery.