Kazakh protests alter balance of energy geopolitics in Eurasia

by Dr Kaho Yu,

On 11 January, Kazakh President Tokayev announced that Russian-led peacekeeping forces had successfully completed their mission of quelling the previous week’s unrest and would leave the country in 10 days. On the same day, the president named a new cabinet that included a pro-investor and pro-reform energy minister, Bolat Akchulakov.

But the violent events in Kazakhstan and the intervention of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) – a security alliance made up of former members of the Soviet bloc – are a reminder of the geopolitical risks facing foreign companies with mega-energy projects in Central Asia.

And although production disrupted by the unrest has resumed quickly in Kazakhstan, the cabinet reshuffle means that regulatory instability remains. Political struggle and targeted reforms by the new leadership will continue to challenge the old energy regulatory system in which billionaire oligarchs flourished. The balance of power in the region will also likely alter energy trade and contract negotiations.

Russia to fill security vacuum for its Eurasia ambitions

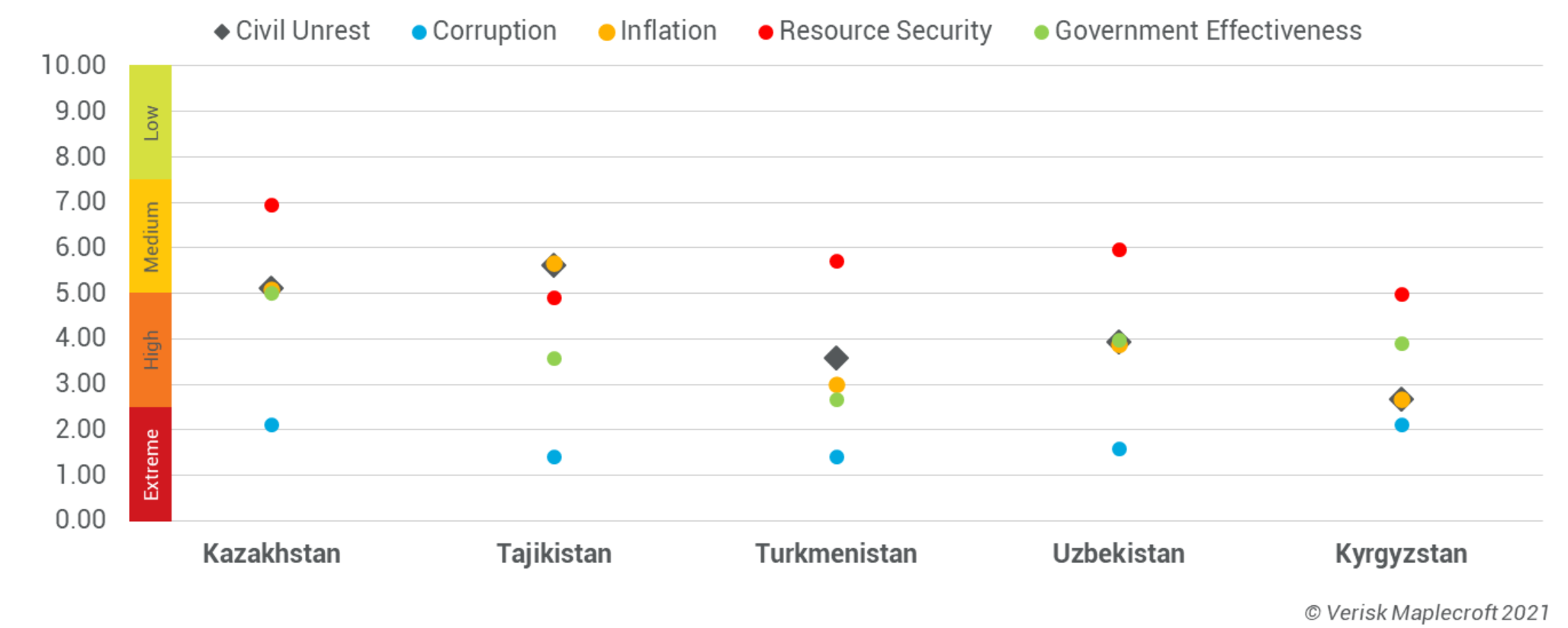

Turmoil in Kazakhstan is unlikely to be an isolated case in Central Asia, given that the difficult power transition away from ageing leaderships means ineffective governance continues across the region. Besides, most Central Asian countries are facing similar structural challenges (see chart below) that could fuel protests.

The impact of low oil prices and the global move to curb fossil fuel investment on Central Asian economies means they cannot afford to target sufficient national expenditure at building up their security forces to tackle domestic unrest and regional instability. Since increasing stakeholder and regulatory pressure further discourages new investment in fossil fuel projects in Central Asia, we expect deteriorating economic conditions to hamper Central Asian governments’ efforts to address social and economic inequities, fuelling future unrest.

Since it has become more difficult for Central Asian countries to tackle security issues on their own, we expect the frequency of security intervention from Russia in the region, via the CSTO, to increase. Although prompt military support could help ensure stability in Central Asia, it allows Russia to advance its long-standing ambitions of building a more united Eurasia.

It also allows Russia to have more leverage over the oil and gas trade in the region. For example, Russia has been using its influence as leverage in handling energy trade and competition with Turkmenistan in recent years. After all, Russia and Central Asian countries are targeting investment from the same group of consuming countries, such as European countries, China, India and Japan.

Given the limited capacity of domestic firms, Kazakhstan and other Central Asian countries will have to continue relying on the expertise of foreign resource companies to grow the country’s oil, gas and mineral production. Chinese, American and European energy giants, especially those with a slower transition plan, will continue to lead investment in the region. However, these foreign investors will likely have to contend with local discontent and geopolitical risks.

Find out more about our Country Risk Intelligence service

Imports diversification the key to China’s energy security

Risks associated with these political and geopolitical dynamics are particularly acute for energy operators from major consuming countries, such as China, which have traditionally considered Central Asia a stable region for energy supplies.

Kazakhstan is a major oil and gas supplier to China as well as a transit country for the China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline. Although Chinese energy and infrastructure projects are located far away from protest locations, such as Almaty, on 5 January the Chinese Embassy in Kazakhstan asked Chinese companies to raise safety awareness and introduce emergency plans.

We believe China will re-assess the reliability of Kazakhstan as a supplier and a transit country for oil and gas. President Xi has been emphasising the urgency of energy security since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the risks of supply chain disruption.

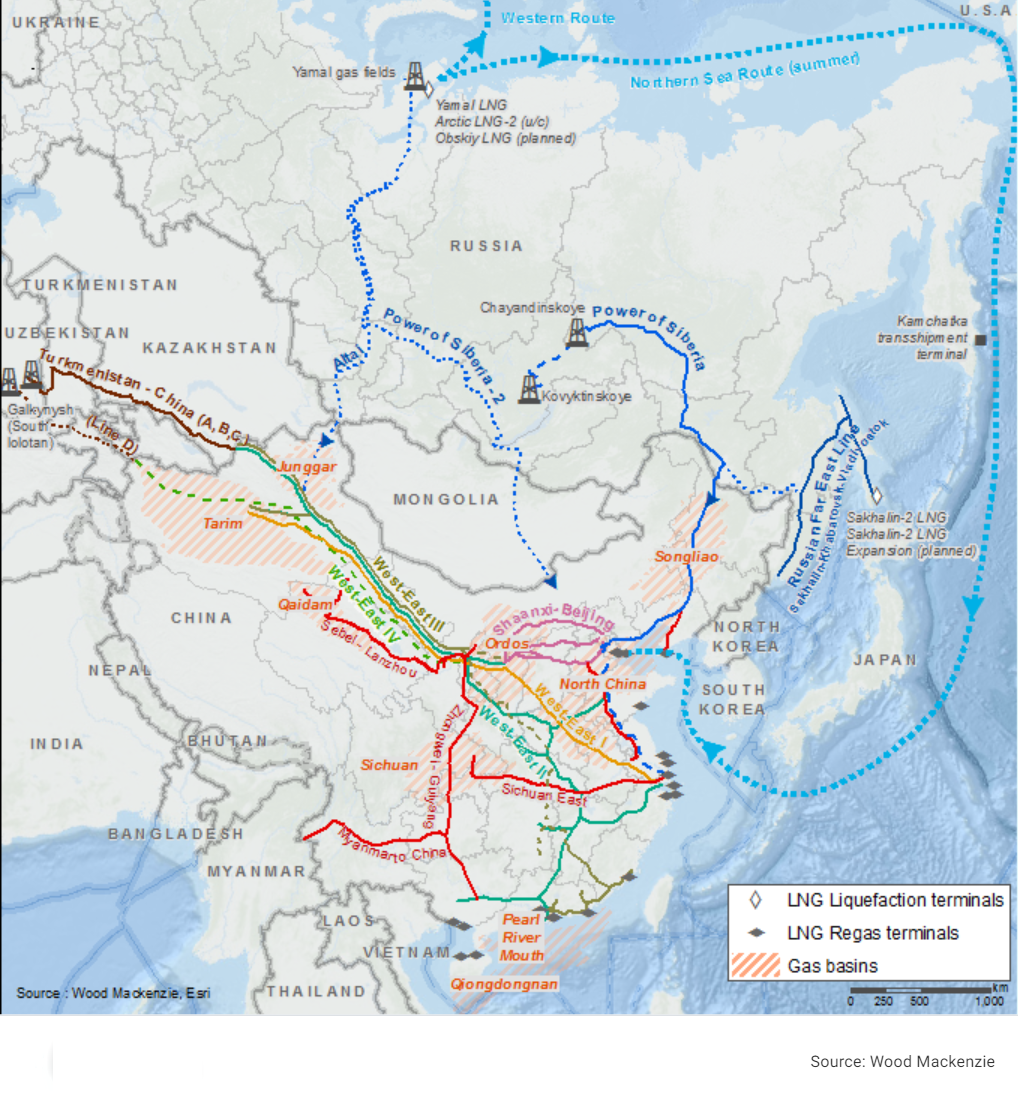

In order to enhance energy security, China will continue its diversification strategy for energy imports (see map below) alongside its drive for more domestic production. For example, Line D of the China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline (the construction of which has been delayed) will not pass through Kazakhstan. China will also likely make headway towards importing more Russian Arctic LNG or constructing a potential Power of Siberia-2 gas pipeline passing through Mongolia. China is also reportedly targeting more LNG imports from the US. Several Chinese companies have signed up long-term contracts to buy US LNG, making the United States China’s second-largest LNG supplier, despite bilateral tensions.

While we expect the burgeoning trade between Russia and China to reinforce closer political and strategic cooperation, their energy relationship will continue to be asymmetrical, with Moscow a junior partner operating in a buyer’s market. In contrast, although there is a strong commercial logic in the US-China energy trade, the fundamental difference between Beijing and Washington will continue to limit the scope for improvement in their bilateral relations.