Everything you need to know about the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (UFLPA)

by Sofia Nazalya,

US bipartisan efforts to target forced labour in supply chains continue to build with the reintroduction of the Slave-Free Business Certification Act of 2022 in February 2022. If enacted, the bill will be part of a growing global list of human rights due diligence laws designed to target the use of forced labour by imposing mandatory reporting and annual supply chain audit requirements on large companies. An earlier result of strong bipartisan support is the landmark Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (UFLPA), and its enforcement will have significant implications not only for China-based operations, but also for how companies approach supply chain due diligence.

As companies gear up for the enforcement of the UFLPA, we provide a list of frequently asked questions regarding the law, its implementation, and other key considerations regarding forced labour in Chinese supply chains and beyond.

Focus box

What is the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act?

The Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (UFLPA) became law on 23 December 2021, creating a "rebuttable presumption" that all goods produced in Xinjiang are made with forced labour and are therefore banned from entering the US. The law's requirement to "ensure that goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labour... are not imported into the United States" necessitates a level of traceability that most, if not all companies, are likely to find incredibly challenging without comprehensive supplier mapping and due diligence.

Learn more about our Risk advisory solution, Sustainable procurement.

1. My sector is identified as high risk under the UFLPA. What can I expect in terms of enforcement?

Cotton, tomato products and polysilicon have been identified as high-risk sectors under the UFLPA, and we expect that these industries will have to pay closer attention to gaining full visibility of their entire supply chain. We expect the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to crackdown on high-risk sectors, so companies in these sectors must be prepared for enhanced CBP checks. For example, if you are an apparel company importing finished garments from Bangladesh, you may have to present appropriate documentation proving that your raw materials are not sourced from Xinjiang. While it may take some time for such enhanced enforcement to really kick-off, it would not be prudent to wave off the possibility of non-Xinjiang or non-China imports undergoing more thorough checks.

2. The UFLPA states that importers can provide “clear and convincing evidence” to rebut the forced labour presumption. What evidence must I submit to satisfy these criteria?

Clarity on what constitutes as “clear and convincing evidence” is expected in the upcoming guidance that will be issued by the interagency Forced Labour Enforcement Task Force (FLETF) by 21 June 2022. The UFLPA tasks the FLETF with the responsibility of establishing a strategy to guide implementation of the law. The guidance will detail the type, nature and extent of evidence needed and is also expected to provide details on due diligence, effective supply chain tracing and supply chain management measures.

During this interim period, companies may refer to existing US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) guidance to assess what is already expected of companies in terms of clear and convincing evidence needed to comply with existing Withhold Release Orders (WROs). We expect that the upcoming UFLPA guidance will meet, at the very least, this existing standard, although it is likely that the evidentiary standard will be higher than previous instances.

3. My sector is not among those identified as high risk. Does the law still apply?

Yes, the law establishes a region-wide presumption of forced labour throughout Xinjiang, and therefore applies to all sectors operating in Xinjiang. While high-risk sectors are likely to be subject to the greatest crackdown, companies participating in other sectors that continue to import Xinjiang-made products will be in violation of the UFLPA and likely subject to civil or/and criminal penalties.

The latest version of the Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory issued by US government agencies in July 2021 provides a list of industries considered as heightened risk for forced labour. The list includes cell phones, electronics, gloves, toys, cleaning supplies, among others. The advisory also states that there is also evidence of forced labour in the mining of coal, uranium and asbestos in the region. While it remains to be seen whether these commodities will be reprioritised as high risk within the scope of the UFLPA in the coming months, it is likely that enforcement bodies will devote significant resources to monitoring compliance in these sectors.

4. What penalties can we expect if found non-compliant?

The US government is authorised to impose visa and financial sanctions, export restrictions and import controls on companies found in violation of the UFLPA. Significantly, while the UFLPA bans the import of Xinjiang goods, it also authorises the US government to impose sanctions on enterprises not involved in export to the US, so long as Uyghur forced labour is found in their supply chains. This would implicate tertiary sectors, such as the services or hospitality industries, that are not involved in the export of goods in the US but may be identified as using Uyghur forced labour nonetheless.

5. What about moving my supply chain out of Xinjiang but still within China? Will this be sufficient to comply with the UFLPA?

The provisions of the UFLPA apply only to the Xinjiang region, however it is important to consider that the FLETF’s upcoming enforcement strategy will also include an assessment of forced labour across China, and not just limited to Xinjiang. This does not mean that there will be an extension of similar measures to other Chinese provinces – in our view this is unlikely – but it does mean that US enforcement agencies will have their eye on entities working with the regional government in Xinjiang that transfer Uyghur labour to other regions in China.

6. Am I genuinely able to mitigate forced labour risks if I shift operations out of Xinjiang to elsewhere in China? Or out of China?

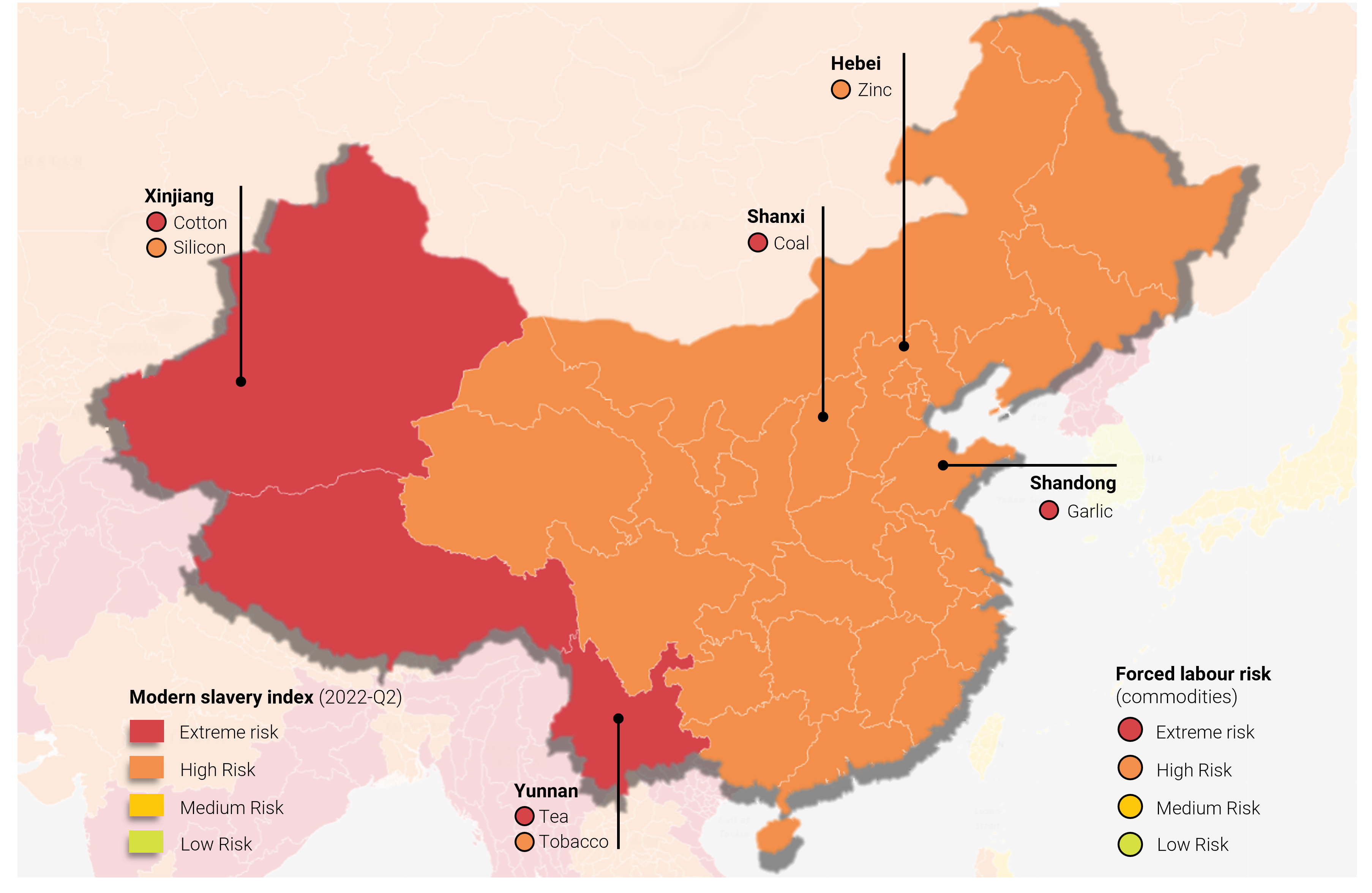

Forced labour risks are widespread, although it must be noted that the challenges specific to Xinjiang are unique, particularly in light of the obligations bestowed on business arising out of the UFLPA. As our subnational modern slavery data shows (see visual below), Xinjiang, alongside Tibet and Yunnan record the worst-possible scores for the pillar measuring on the ground violations in our Modern Slavery Index. The embedded and structural nature of forced labour in Xinjiang is particularly challenging for businesses to overcome, as it makes it practically impossible to conduct traditional due diligence that will be considered sufficient or that meets international standards.

Our data shows that forced labour risks remain high elsewhere in China, although the circumstances are particularly unique in Xinjiang and Tibet as forced labour arises out of a system that targets specific minority groups in these regions. It is to this end that legislation such as the UFLPA has come to be formed, therefore creating specific compliance challenges for business. Nevertheless, extreme forced labour risks are prevalent globally – whether that’s in the sourcing of cocoa in Côte d'Ivoire, rubber in Thailand or copper in DR Congo. Accurate identification of the risk exposure to forced labour, both on a country and commodity level, is an important step to conducting human rights due diligence, and can aid in meeting the obligations laid out in the UFLPA.