EV battery disposal sparks ESG risks

by Will Nichols,

Almost every month brings another national target to replace internal combustion engine vehicles with cleaner battery electric and plug-in hybrid cars. Our sister company, Wood Mackenzie, expects electric vehicles (EVs) will account for around a quarter of global new car sales by 2035. But the growing number of EVs raises questions around battery disposal and how to ensure the valuable materials they contain aren't lost.

Recycling a waste battery mountain raises a host of ESG risks, ranging from new regulations on businesses and producers, to pollution and even human rights violations. China, expected to account for around a third of global EV sales in 2040, is a hotbed for such ESG issues. Meanwhile, expected supply shortfalls of battery raw materials could see national governments scrambling to hold on to batteries.

These threats will only meaningfully materialise post-2030, but companies in the value chain that can address end of life risks today will be better able to manage and exploit the future risks and opportunities inherent in recycling valuable and increasingly scarce materials.

Learn more about how we can help you with ESG risk

Why recycle batteries?

Even at the end of their life, EV batteries contain a host of valuable materials, such as cobalt, nickel, and lithium. Projections from Wood Mackenzie suggest all these key battery metals will enter a deficit before 2025 under an accelerated energy transition scenario, resulting in a supply shortfall.

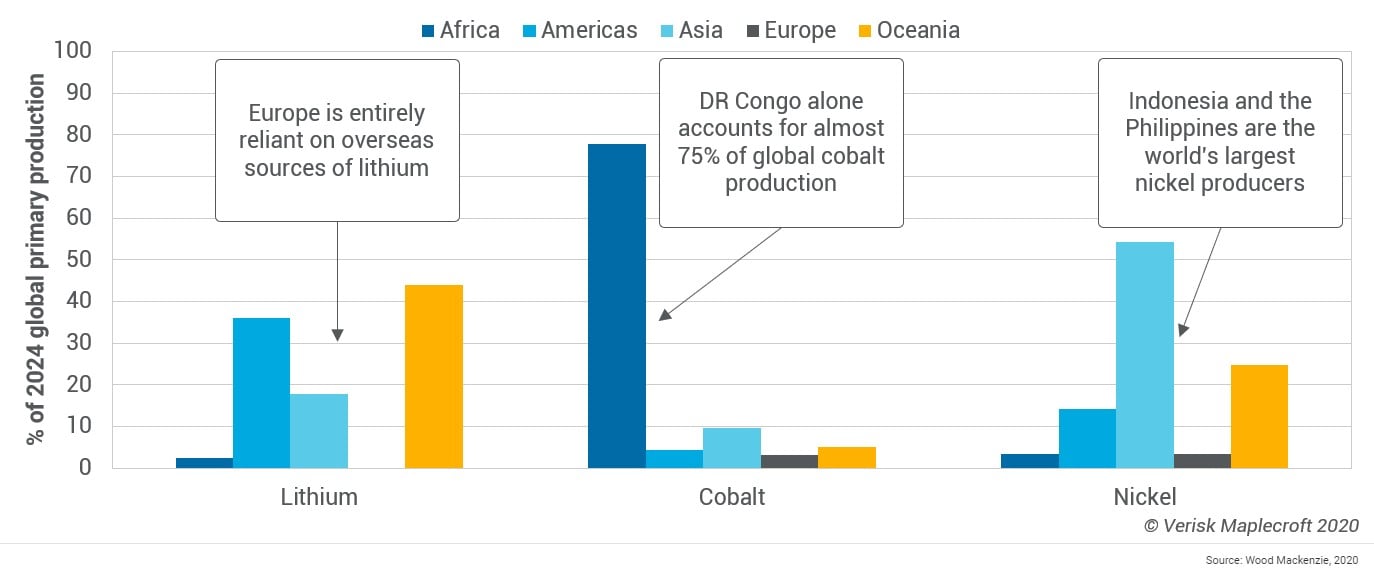

Countries across the globe are gearing up to electrify transport networks in the same timeframe, ramping up demand for materials. Interruptions to the dominant supply chains of raw materials from Asia, where most mined material is sent to be processed into battery-grade material, threaten those ambitions for nations in Europe and North America (see chart below).

A substantive domestic recycling programme would create a secure supply of raw materials while also reducing the volumes of mined materials required, limiting certain ESG issues such as the child labour violations associated with cobalt produced in the DR Congo or water conflicts in South America's arid 'lithium triangle'.

What are the risks for companies?

Government efforts to recycle EV batteries throw up a host of risks and opportunities for companies involved in their production.

1. Governance risks

Regulators in the US, the EU, and China are all at different stages of discussing extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws for EV batteries. EPR laws mandate producers to deal with their product after consumer use. Specific laws for consumer batteries for items like phones and laptops already exist in China and Europe, while Brussels is set to table regulations on EV battery reuse imminently as part of a wider raw material strategy aiming to ensure EU-made batteries use sustainably sourced materials free from ESG issues.

Meeting EPR and recycling laws would demand substantial investment in collection and processing facilities. EV producers could spread the costs through partnerships with peers or industrial processing companies that possess the expertise and machinery needed to extract post-consumer materials.

Outsourcing is a cheaper option, but handing over control of processing and product materials - most likely to China and Asian processing hubs - leaves companies exposed to environmental and social risks. The value of batteries and projected future shortages of key materials raises the prospect of countries trying to keep batteries within their borders, potentially leaving companies at the centre of a tug of war for materials. Until legal obligations and liabilities are clear and consistent, companies caught up in the battery reprocessing value chain face real uncertainty.

Read more on conducting Human rights due diligence

2. Environmental risks

Recycling batteries involves using heat to siphon off desired materials (pyrometallurgical process) or aqueous chemical processing (hydrometallurgical). The former is a well-established technology that requires smaller plants, while the latter recovers more high-quality material but requires large processing facilities and much costlier residue management due to the chemicals involved.

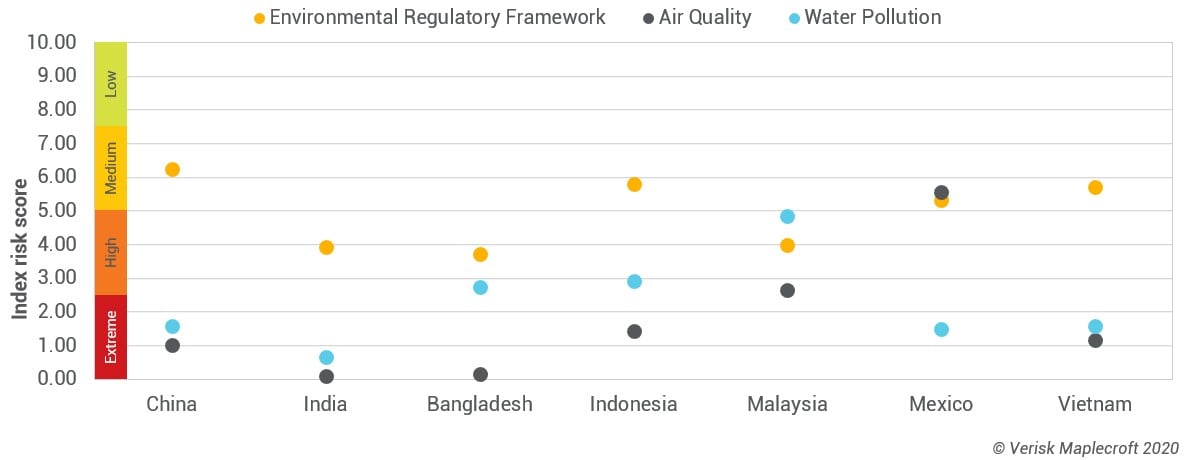

Strong oversight is needed to avoid pollution from these sites, both from fumes to the air and chemical releases to water sources or the surrounding environment. Such oversight is relatively reliable in many countries leading the EV charge, such as the UK, Germany, Japan, and the US. But environmental risks spike in China and India, which together are expected to comprise close to 45% of global EV sales in 2040.

It is a similar picture in nations where battery processing might be outsourced. Despite fairly robust laws in place, as shown below by the scores in our Environmental Regulatory Framework Index, lower Water Pollution and Air Quality scores indicate that in many cases these laws are ineffective. Companies outsourcing battery recycling to these countries are exposed to substantial liabilities, reputational risks, and potential clean-up costs.

3. Social risks

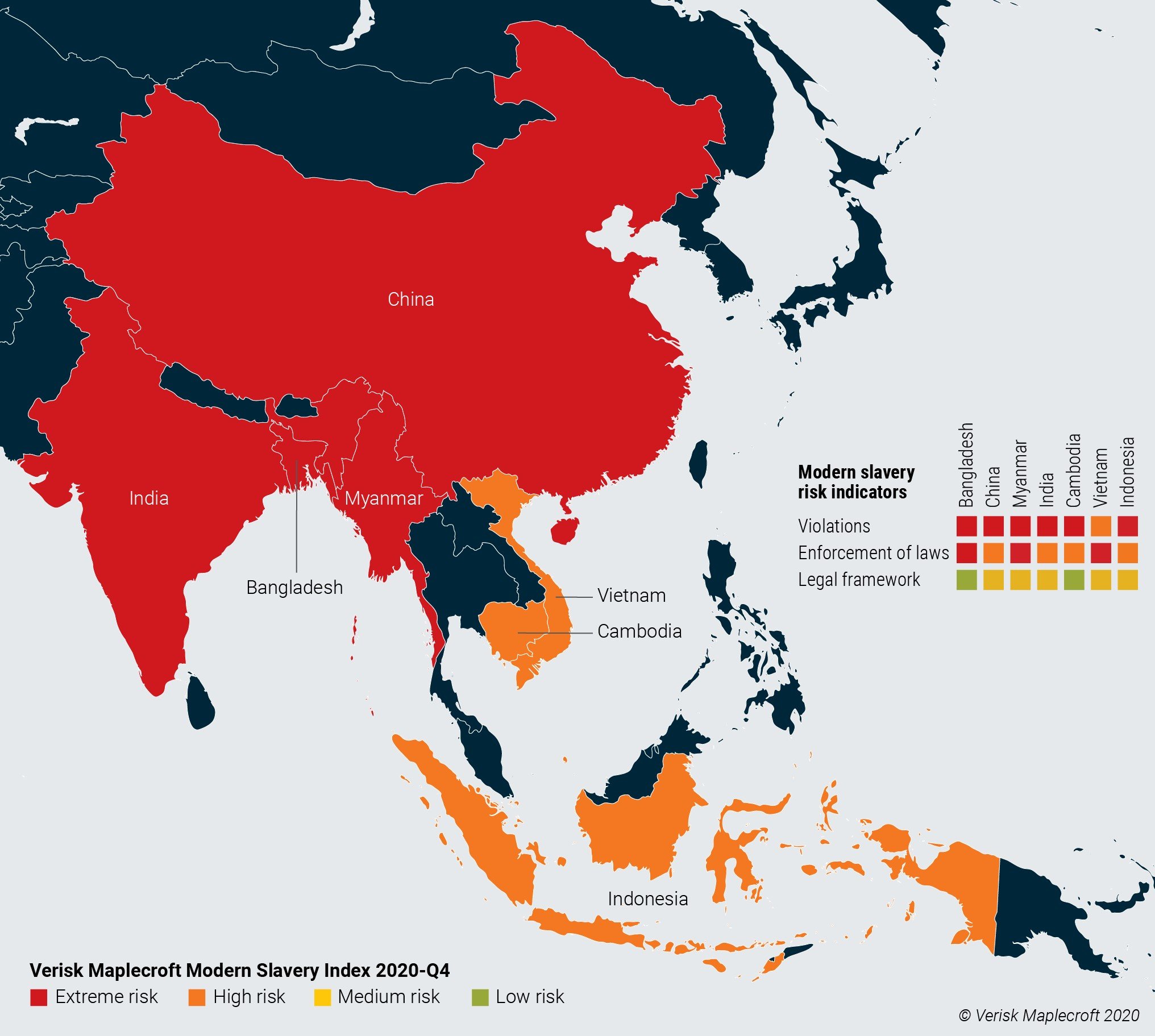

Developed markets typically exhibit social risks, but countries where batteries are likely to be sent for recycling tend to have less robust safeguards. The map below shows Asia, currently the dominant recycling centre, as a hotspot of modern slavery violations, a host of which have been reported in the region's electronics industry.

This poor track record suggests that an emerging battery recycling sector would be equally prone to labour and human rights violations. Manufacturers seeking to recycle batteries in the region would therefore face significant reputational risks.

Looking ahead

The ESG risks we have highlighted are unlikely to become material until after 2030 and even then the use of old EV batteries for stationary storage extends that timeframe further. However, legislators and companies involved in the battery value chain need to be aware that a coming supply crunch and more wide-ranging regulations will mean large investments in recycling capabilities and a host of associated ESG risks.

Even so, early movers will be better placed to cope with incoming EPR regulations and shield themselves against any supply shortages, while the demand for - and value of - battery materials will drive innovation in the recycling market. We are already seeing start-ups embracing the circular economy and focusing on maximising material recovery, an effective way of dealing with both supply shortages and ESG issues.