Crises loom as Taliban returns to power

by Joseph Parkes,

The collapse of the Afghan government leaves the Taliban set to declare the restoration of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, marking a return to power almost 20 years after they were ousted in the US response to the 9/11 attacks. A worsening of Afghanistan’s acute humanitarian crises is now inevitable, and Afghanistan’s neighbours will face cross-border instability and security risks, with the latter likely to be the driving factor behind increased engagement from Beijing.

A more moderate tone but human rights landscape to deteriorate further

The defeat of the Afghan government was expected once the US and international partners opted to withdraw. But the speed of the Taliban’s return to power has nonetheless come as a surprise. The fact that numerous provinces fell without a fight – after deals were struck between the Taliban and local leaders – demonstrates that the Afghan government had little domestic political legitimacy and was not able to inspire resistance by the military or the population at large.

The immediate fallout will be a dramatic escalation of the existing humanitarian and refugee crisis in the country. The number of internally displaced people has soared and chaotic scenes at Kabul airport will be only the start of a large-scale flow of refugees.

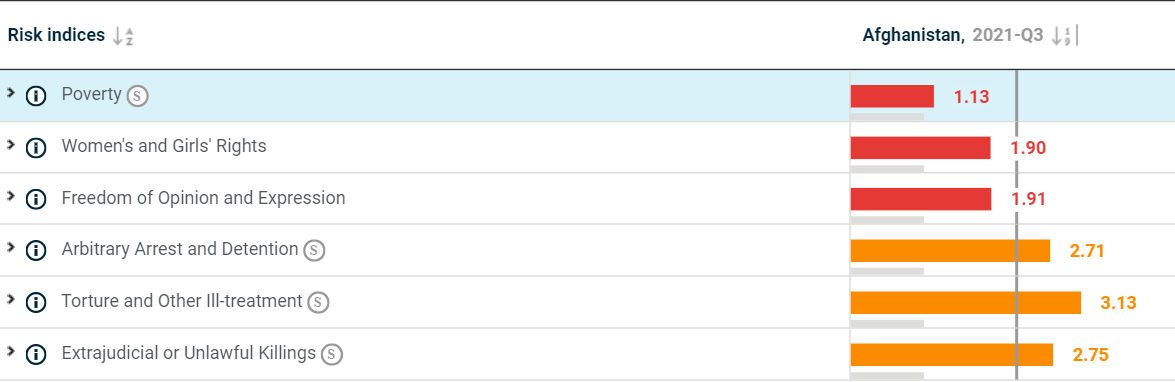

Despite conciliatory words from the Taliban’s spokesman that those who worked with international forces or otherwise opposed the group will not face reprisals, reports are already emerging that local Taliban commanders are not following this line. Women and girls who have taken advantage of increased opportunities to participate in society in areas controlled by the government also face a stark future. Afghanistan is already among the world's highest risk countries across our key social risk indices (see below), and the Taliban’s return to power will lead to further deterioration.

With a Taliban government now a reality, the best-case scenario for western powers is that the rapid Taliban takeover avoids further destructive fighting and a power vacuum that could see international militant groups rapidly gain a stronghold. But the country is deeply divided with numerous factions opposed to Taliban control, which leaves civil war and further regional instability a distinct possibility.

US withdrawal leaves opening for Beijing

The developments inevitably have significant geopolitical implications, not least for Afghanistan’s neighbours. The Taliban’s return power arguably represents a strategic gain for Pakistan, though not an unqualified one. Pakistan’s powerful intelligence agency has longstanding links with the Taliban and has been wary of growing cooperation between the Afghan government and India. However, each of Afghanistan’s neighbours will likely be preoccupied with the inevitable security risks associated with instability across their borders over the coming months, with Pakistan most exposed.

Despite the deteriorating picture, there is only a remote prospect of a substantial re-engagement from the Biden administration beyond the short-term deployment required to facilitate the safe withdrawal of remaining US and international personnel. The war in Afghanistan has largely lost its domestic political traction in the US and the withdrawal is likely to remain popular, barring significant American casualties during the final stages. Biden confirmed as much in his public remarks on 16 August.

Yet, while polls indicate withdrawal commands a plurality of support, sustained criticism from lawmakers and prominent military and intelligence officials over the administration’s handling of US troop removal could inform a perception of foreign policy incompetence that may cast a long shadow over Biden’s first term agenda.

The US and international withdrawal creates an opening for Beijing to increase its influence in Afghanistan, but security interests are likely to be the motivating factor beyond geopolitical ambitions. Beijing fears the potential for Uyghur-led militant groups to use Afghanistan as a base from which to destabilise China, and it can no longer rely on the US to patrol the field. A Taliban delegation visited Tianjin last month and met with Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, demonstrating that Beijing is prepared to work with whoever holds power in Kabul.