Cost of living crisis inflames civil unrest risks in emerging markets

Political Risk Outlook 2022

by Hamish Kinnear and Jimena Blanco,

Brazil, Egypt, Tunisia among countries to watch

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is supercharging food and fuel prices and stoking a cost-of-living crisis across the globe. However, the worst effects are yet to kick in. As rising inflation and government cutbacks bite households harder, we see a rise in civil unrest as inevitable across key emerging economies that will have likely knock-on impacts for political stability and investor confidence.

Middle-income economies struggling with the public purse will be most at risk. According to our Civil Unrest Index Projections, 10 of these countries – including Brazil, Egypt, Tunisia, Pakistan and Senegal – are in line to take the hardest hit over the next six months. Some countries risk falling into a vicious cycle, whereby worsening governance and social indicators make them ESG investment pariahs, impeding the inflows needed to improve economic performance and address societal needs.

Pandemic, strained supply chains, inflation, and war drive spike in civil unrest risk

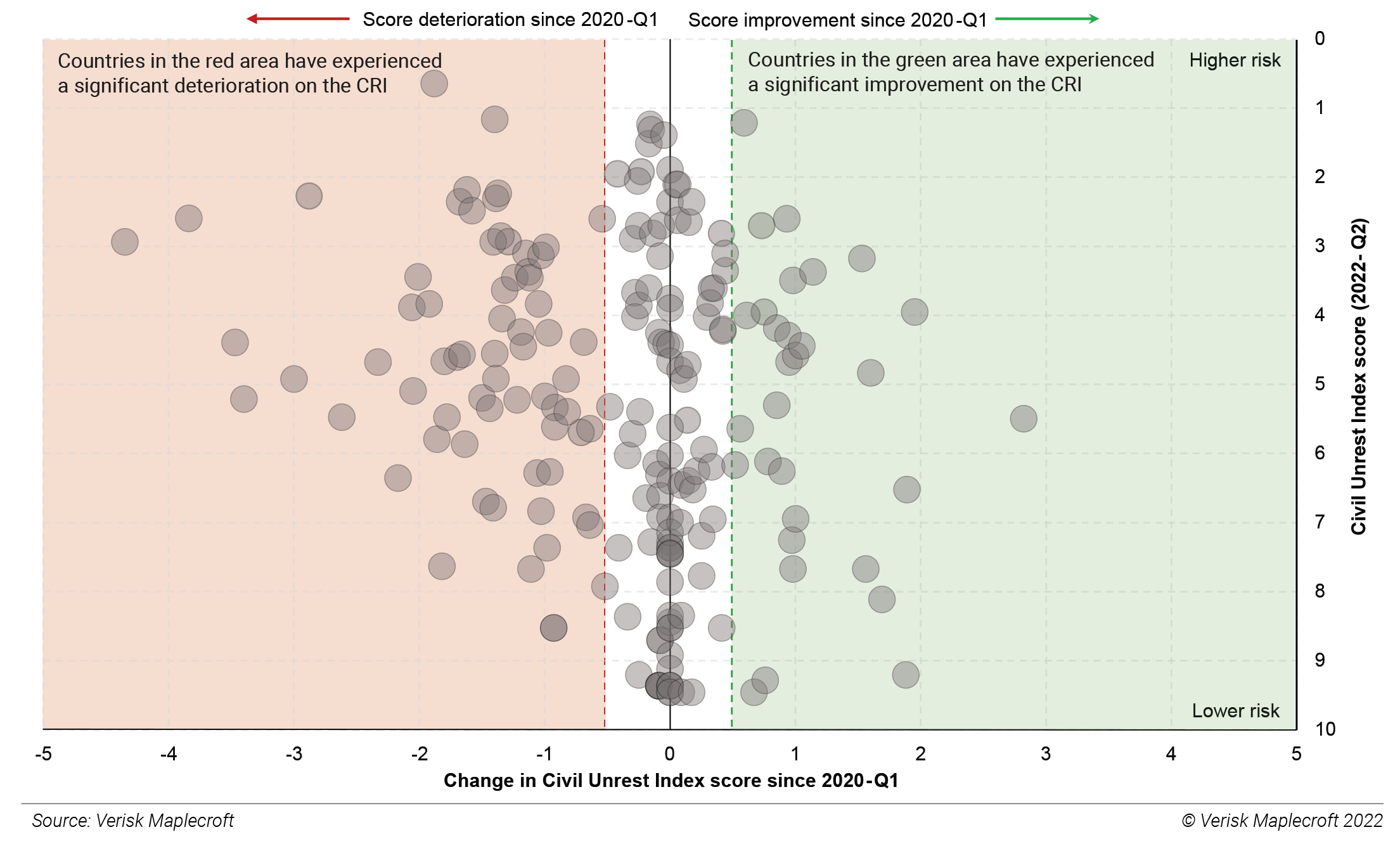

Over half of the world experienced an increase in civil unrest risk since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The latest iteration of our Civil Unrest Index shows that 107 out of 198 (54%) assessed countries recorded a deterioration in their score since 2020-Q1 (see Figure 1), compared to 31% that have improved and 15% that have remained static. Indeed, 68 countries (34%) experienced a significant deterioration – which we define as a decrease of 0.5 or more in their score.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made a bad situation worse, causing instant disruption to energy markets and food supply chains, and provoking further price rises. With no resolution of the conflict in sight, the global cost of living crisis will continue deep into 2023.

Middle income countries most at risk

The global cost of living crisis will weigh on governments worldwide, but our data shows that middle income countries are most at risk. This is reflected in our Civil Unrest Index Projections, which provide a six-month outlook for 132 countries. Three-quarters of the countries that are projected to be in the high-risk or extreme-risk category of our Civil Unrest Index by 2022-Q4 are classified as lower-middle or upper-middle income countries by the World Bank.

So, why are these countries most at risk? Unlike low-income countries, they were rich enough to offer social protection during the pandemic, but now struggle to maintain high social spending that is vital to the living standards of large sections of their populations.

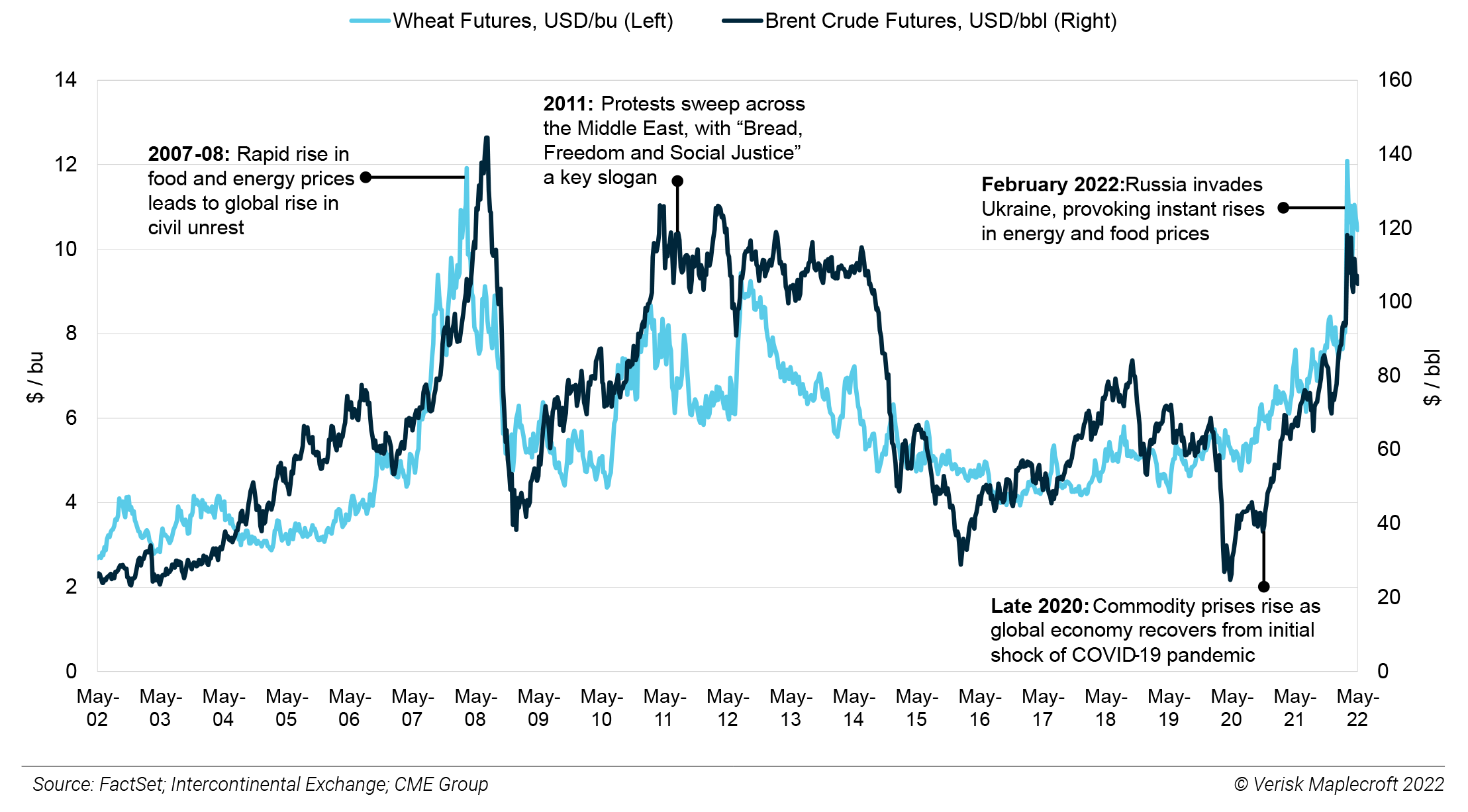

The war in Ukraine and its catalysing effect on food and fuel prices (see Figure 2) is putting balance sheets under further pressure, particularly for countries that are dependent on food and fuel imports and/or maintain a system of subsidies on basic goods. The middle income countries of Sri Lanka and Kazakhstan have already experienced destabilising unrest this year. In Sri Lanka’s case rising food and fuel prices were a key factor; while Kazakhstan’s attempt to cut fuel subsidies was the spark.

Ten countries to watch

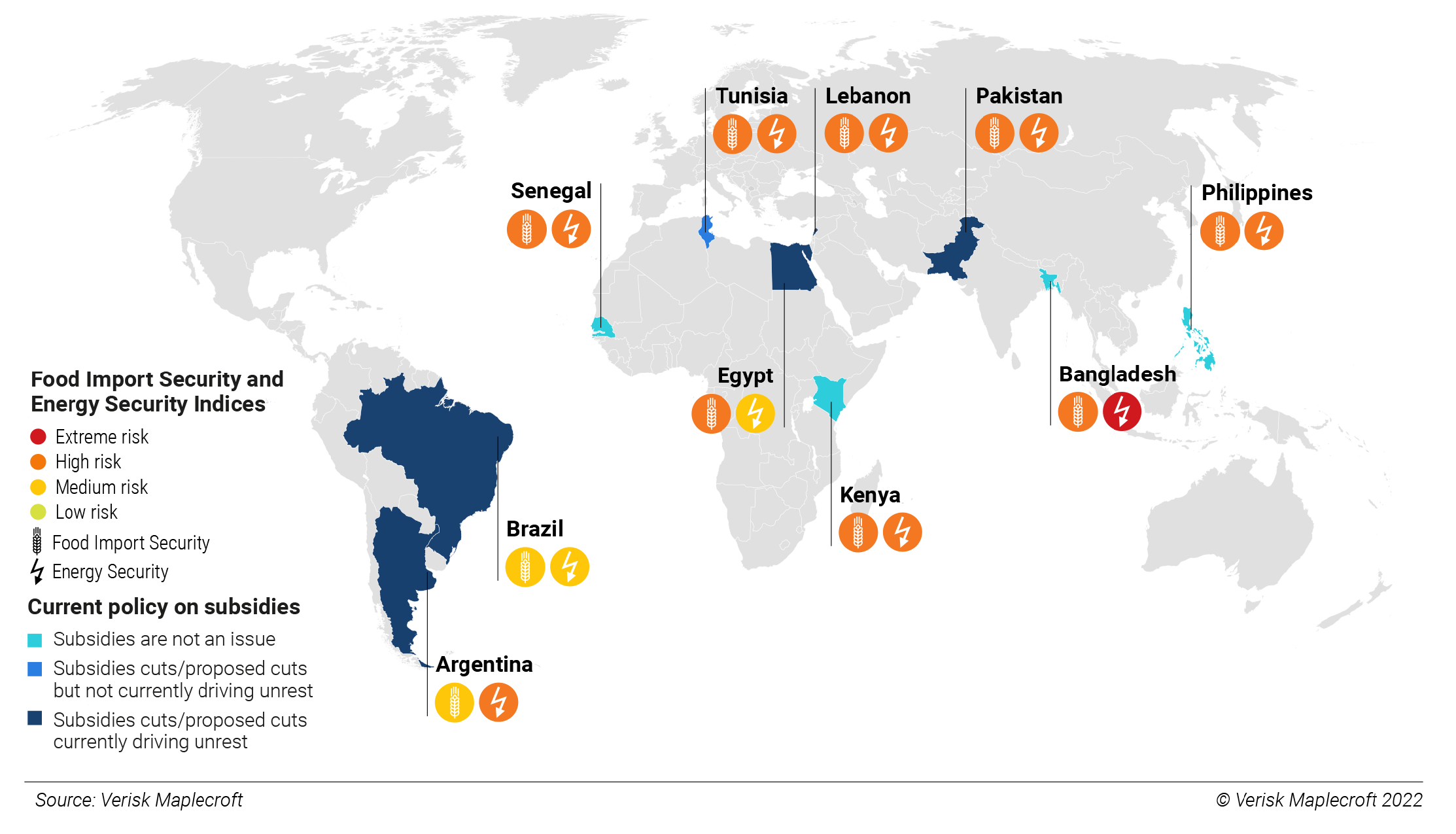

Sri Lanka and Kazakhstan will not be the last to experience destabilising unrest this year. We’ve identified 10 emerging markets facing similar pressures that are particularly worth watching, including: Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, Tunisia, Lebanon, Senegal, Kenya, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and The Philippines (see Figure 3).

That the Middle East and North Africa region accounts for 3 of 10 of our countries to watch should come as no surprise. The region is dependent on food imports, leaving it vulnerable to price rises, and has traditionally sourced significant proportions of its grain from Ukraine and Russia, subject to disruption due to the war. While rich hydrocarbon producers such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia can handle the premium on grain imports and are benefitting from higher energy prices, poorer, import-dependent countries like Egypt, Tunisia and Lebanon are far more exposed.

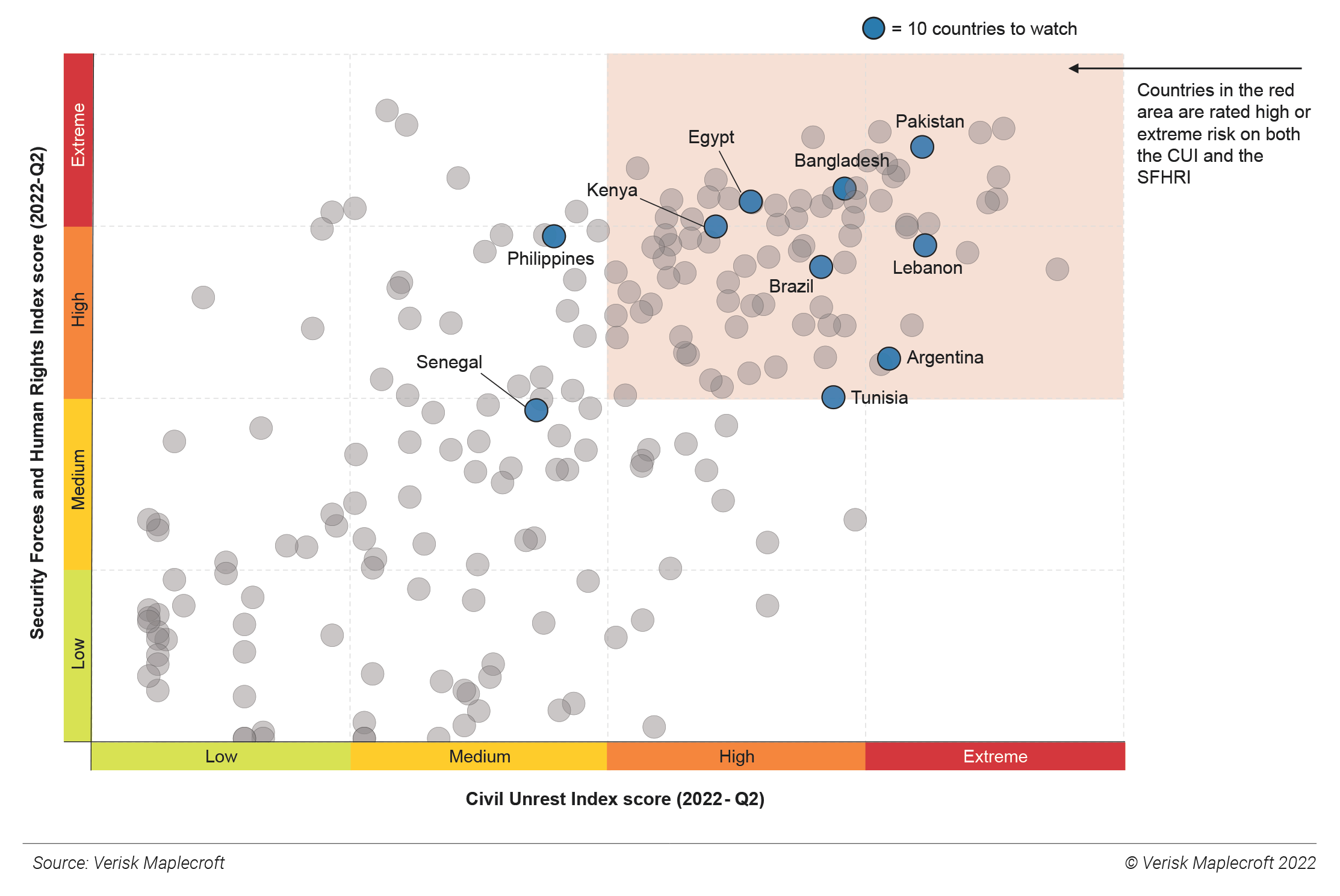

All three are currently seeking IMF support to offset the risk of financial crisis. Cuts to food and fuel subsidies programmes are often set as conditions for accessing financing, meaning that further, painful price rises for citizens are increasingly likely. Mass civil unrest in response is therefore a possibility, which we expect will be met with a violent state crackdown in countries that have a poor record when it comes to security forces and human rights (see Figure 4).

In Sub-Saharan Africa, drought in Kenya is leaving the country even more dependent on costly food imports, while the government’s struggle to cushion the impact of rising prices on the general population will play a key role in upcoming elections in August 2022. The rising cost of living will also play a key role in Senegal, set to hold legislative elections in July 2022. We expect a rise in civil unrest in both countries in the run up to the polls.

In the Americas, high fertiliser prices (also provoked by the Russian invasion of Ukraine) will increase the cost of food in Brazil and Argentina, while high inflation and cuts to subsidies programmes will exacerbate rising living costs. Inflation was already the backdrop of a politically tumultuous year for Brazil, hitting a six-year high of over 10% in 2021. And the cost of living may become the Achilles heel of President Bolsonaro’s re-election bid as the resurgent former president Luiz Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva promises voters a return to the economic heyday of his first administration. Protests such as a major strike launched by lorry drivers over fuel prices in 2021 are likely to increase in number ahead of the election.

Next door in Argentina, the pandemic delivered a major economic contraction after years of stagflation. With the Fernández administration caught between trying to implement an IMF restructuring while maintaining peace with VP Kirchner, citizens are set to face another record-breaking year of inflation. Indeed, the ongoing power struggle within the ruling coalition will only intensify as the country heads towards a key election year in 2023, meaning that the risk of unrest will grow over the coming 6-12 months.

High food and fuel prices could also be a destabilising factor in Asia beyond Sri Lanka. Bangladesh and Pakistan are highly dependent on food and fuel imports, with the latter seeing a change in Prime Minister in April due in part to economic troubles sparked by rising prices. The rising cost of living will make life hard for the likely victor of the Philippines’ presidential election, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.

Material impacts on business, including ESG concerns

A spike in civil unrest can cause direct disruption to business and commerce. In Tunisia, for example, the blocking of a key oil pipeline in 2017 and 2020 cut off half the country’s oil output, while February’s trucker protest in Canada saw parts of the capital Ottawa shut off for weeks. However, indirect impacts are also a risk, and likely to become more material as businesses increasingly consider ESG risks and regulations.

Indeed, our data also shows how security forces’ poor human rights records often align with higher civil unrest risks, as the repressive response can stoke public anger and worsen civil unrest-related disruption. Figure 4 compares our Civil Unrest Index with our Security Forces and Human Rights Index, which measures the risk of business complicity in human rights violations committed by public and/or private security forces. The key finding is that 85% of countries that are high or extreme risk for civil unrest are also high or extreme risk on our Security Forces and Human Rights Index.

With expected spikes in civil unrest, we can also expect to see a rise in corresponding abuses, making it harder for ESG-conscious businesses to follow through on potential investments or even forcing a withdrawal. The January 2022 decision by TotalEnergies and Chevron that they would withdraw from a gas project in Myanmar, for example, was in part a response to the state’s violent crackdown on anti-coup protestors.

The vicious cycle threat

The top risk for middle-income economies vulnerable to civil unrest risk is that protests not only derail economic recovery in 2022, but also reduce their appeal as investment destinations going forward. As ESG investors reward best performance and reduce exposure to jurisdictions where human rights and environmental risks are highest, the unintended consequence may be one of countries stuck in a vicious cycle.

That is, economies that struggle to grow will leave cash-strapped governments less able to address social discontent, with unrest more likely to spark business disruption and trigger repressive state responses. As businesses become more exposed to unrest and the implications of poor human rights track records, investors will be less likely to choose these jurisdictions, reducing the probability of improvement in the two-three year horizon.