China’s vaccine diplomacy in Africa unlikely to be a geopolitical game changer

by Alexandre Raymakers and Eric Humphery-Smith and Aleix Montana,

With the first batch of COVID-19 vaccines having arrived in Ghana on 24 February 2021 via the WHO’s COVAX initiative, the race to inoculate the African continent is in full swing. With a stated objective of vaccinating 60% of sub-Saharan Africa’s population, Africa’s vaccine drive will require time and considerable stocks of COVID-19 vaccines. Assuming that each inoculation generally requires two jabs, regional governments will likely have to procure a total of around 1.3 billion doses. With African states almost completely dependent on foreign suppliers, China has been particularly eager to offer its domestically produced vaccines in a face-saving bid to portray itself as part of the solution and to enshrine its position as the preferred development partner of African governments.

China eager to enshrine its position as a privileged partner

Amid widespread international criticism of Beijing's handling of the initial outbreak, China is actively seeking to present itself as the solution rather than the ’cause’ of the COVID-19 pandemic. China’s vaccine strategy in sub-Saharan Africa reflects this, and is driven by a desire to protect – and potentially even enhance – its reputation in a region that Beijing views as strategically important and in which it believes it has a diplomatic edge over its geopolitical rivals.

Furthermore, Beijing is benefitting from the growing disenchantment of African governments with their Western partners, who are deemed to be failing to abide by their public commitments to guarantee an equitable distribution of affordable, Western-produced vaccines. Although vaccines developed by Western countries form the bulk of vaccines distributed to the region, Beijing is aware of this growing resentment among African leaders and is looking to capitalise on it.

Find out more about our Country Risk Intelligence

Beyond burnishing its soft power credentials, China will likely seek to leverage any goodwill generated by its vaccine policy to garner African support on political issues of importance to Beijing, such as its territorial claims in the South China Sea or perceived foreign interference in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. However, Beijing will need to tread carefully, as supplying vaccines on a quid pro quo basis risks doing more harm than good. Failing to decouple its vaccine diplomacy in Africa from its commercial interest would strengthen the narrative emanating from Washington and Brussels that Chinese vaccine diplomacy is self-serving. Besides, Beijing can far better leverage its position as a key lender to African governments if its aim is to cement its commercial advantage.

Preference for bilateral agreements will limit the reach of Chinese vaccines

African governments currently have three options to access COVID-19 vaccines: the WHO’s COVAX programme, the African Union’s vaccine acquisition task force or through bilateral agreements with both countries and private companies. Although China repeatedly vaunts the merits of multilateralism, Beijing clearly favours supplying its vaccines through bilateral agreements rather than via multilateral structures. This is likely because China is eager not to dilute any goodwill generated from its vaccine shipments. Indeed, China has currently only pledged to deliver 10 million doses to the COVAX facility. This is a minor contribution when compared to United Kingdom's commitment to provide USD540 million of funding to the COVAX scheme, which will in turn lead to the purchase of a quantity of vaccine exceeding 10 million doses.

Beijing's preference for bilateral deals will likely hinder China's ability to carve out a dominant role in the region's immunisation strategy, given that the majority of doses are likely to come through multilateral structures. COVAX alone is expected to provide up to 600 million doses of vaccines for the most vulnerable 20% of Africa’s population. China’s preference for bilateral agreements will therefore likely limit uptake to countries with which Beijing already has well-established relations, restricting its ability to make any major diplomatic inroads in the region on the back of its vaccine diplomacy.

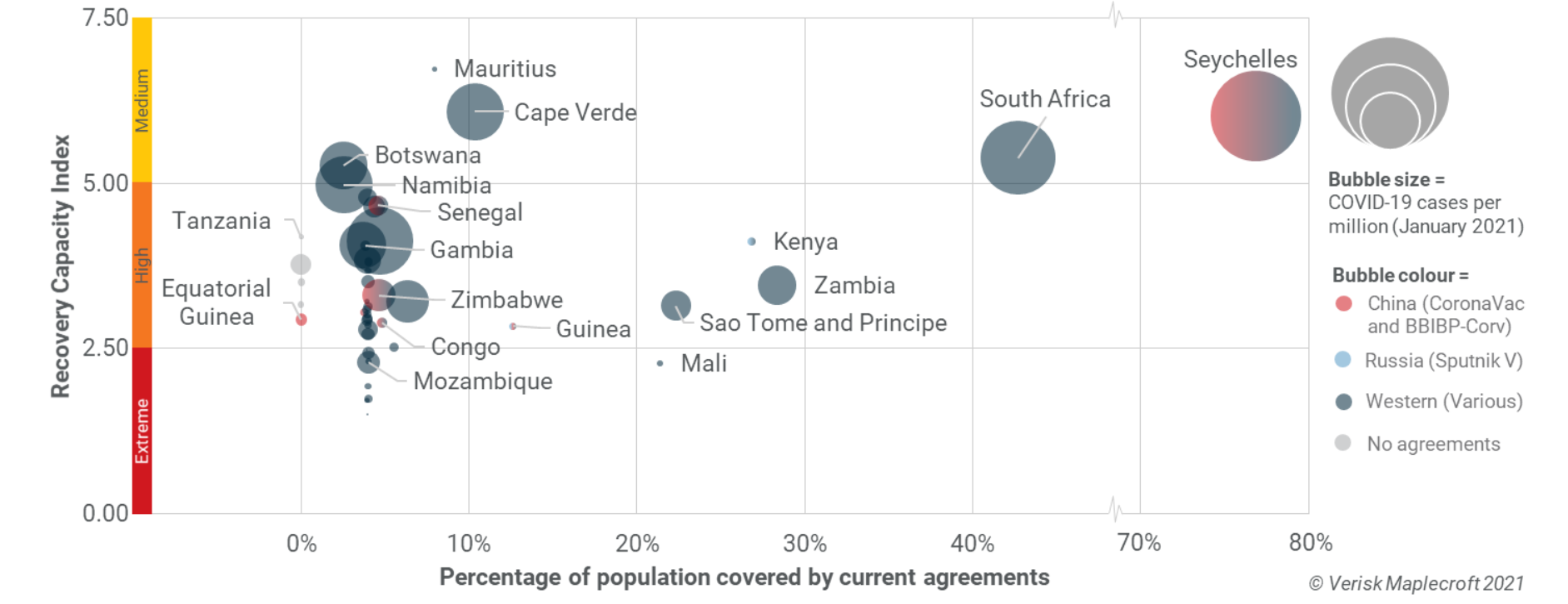

To-date, Beijing has struck bilateral deals with the likes of Republic of Congo, Guinea and Zimbabwe; commodity-rich states that Beijing enjoys warm diplomatic ties with and which are all acutely vulnerable to the adverse impact of the pandemic, as reflected in their categorisation as high risk in our Recovery Capacity Index in 2021-Q2 (see chart below). By focusing its vaccine diplomacy efforts on these countries, Beijing will further entrench its position as a preferred partner.

Domestic priority, competitors and urgency of crisis will curtail Chinese influence

The uptake of Chinese vaccines across the region will be constrained by a number of factors. For one, the Chinese government will need to prioritise vaccine stocks for its domestic immunisation programme, as Beijing can ill-afford to be seen to be neglecting the home front. This may limit the supply of COVID-19 vaccines it can provide to the region bearing in mind it also has ambitions in other parts of the world.

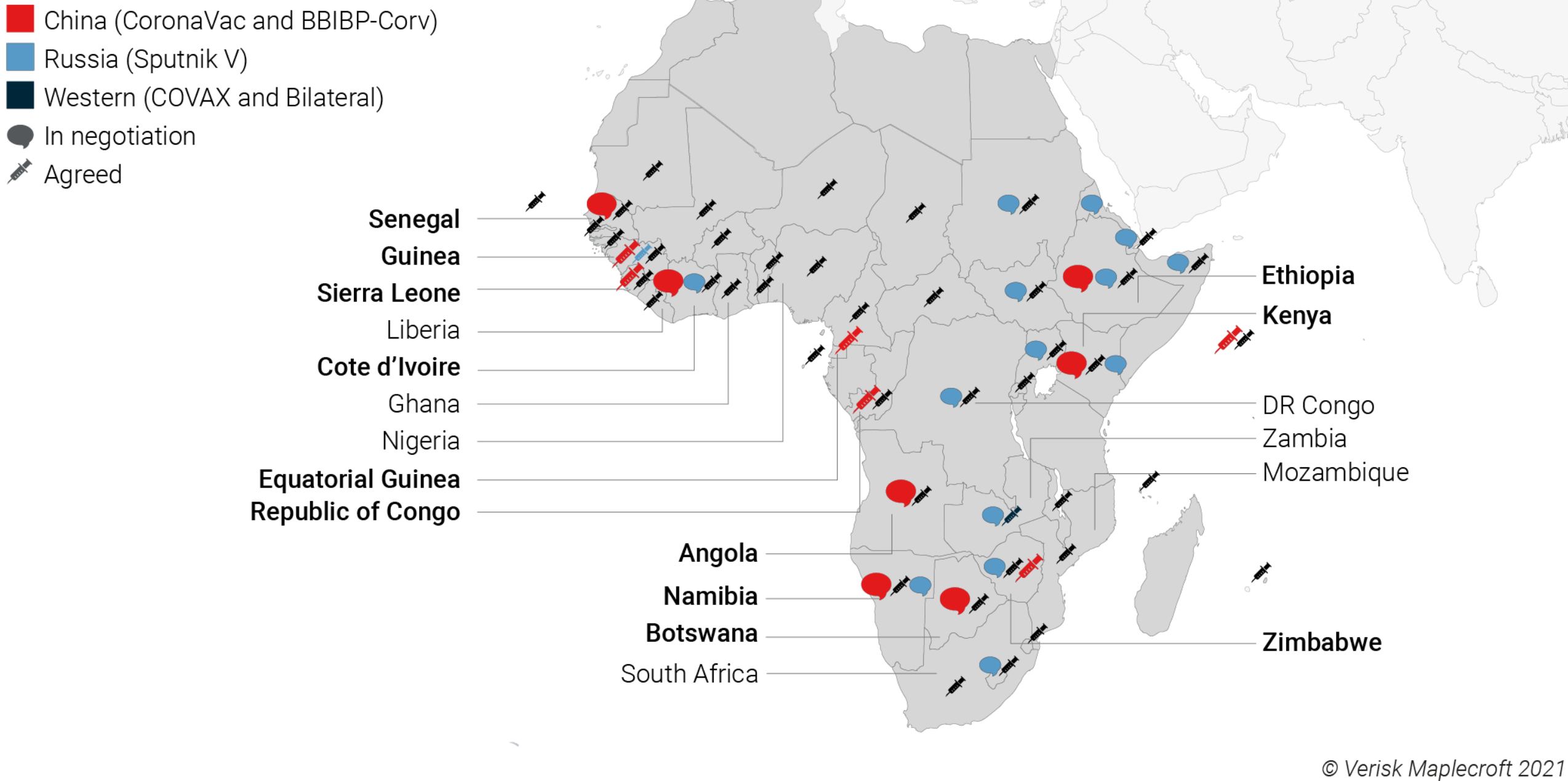

Vaccines from China are also not the only game in town, with a number of other global players such as Russia or India also eager to become the vaccine provider of choice to Africa. Russia has been especially proactive in its efforts to provide its Sputnik V vaccines to African governments (see map below). For instance, the majority of Guinea and Kenya’s COVID-19 vaccine stocks will be Russian Sputnik V vaccines.

Perhaps most importantly, African governments will likely seek to purchase vaccines from a variety of sources, as rapidly securing the necessary vaccine doses is their foremost priority. They are therefore unlikely to become dependent on a single provider, further limiting China’s influence. Only in exceptional cases such as Congo, Guinea, Senegal, Seychelles and Zimbabwe, do Chinese vaccines make up a significant proportion of the total supply. And even in those cases, Chinese vaccines will account only for less than a third of the total (see chart above).

A diplomatic offensive of limited reach

China’s charm offensive has raised concerns that Beijing is seeking to leverage its position as a major manufacture of vaccines to secure commercial and geopolitical advantages across the continent. Certainly, Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy in sub-Saharan Africa should be viewed as a continuation of its efforts to portray itself as an ‘all-weather’ ally to African governments. The impact of Chinese vaccine diplomacy may though be limited. The need to prioritise vaccinations in China and competition from a host of rivals means that China is unlikely to become the dominant provider of COVID-19 vaccines to Africa. Nevertheless, China will likely succeed in strengthening its position as the privileged partner with certain key African allies.