Are Asia’s carbon neutral pledges hot air?

by Miha Hribernik and Dr Rory Clisby,

The Asia Pacific has seen a flurry of carbon neutrality pledges over the past two months. China, Japan and South Korea, the world’s first, fifth and seventh biggest greenhouse gas emitters, have all committed to become carbon neutral. But is this merely a safe play to reassure domestic audiences, international partners and investors?

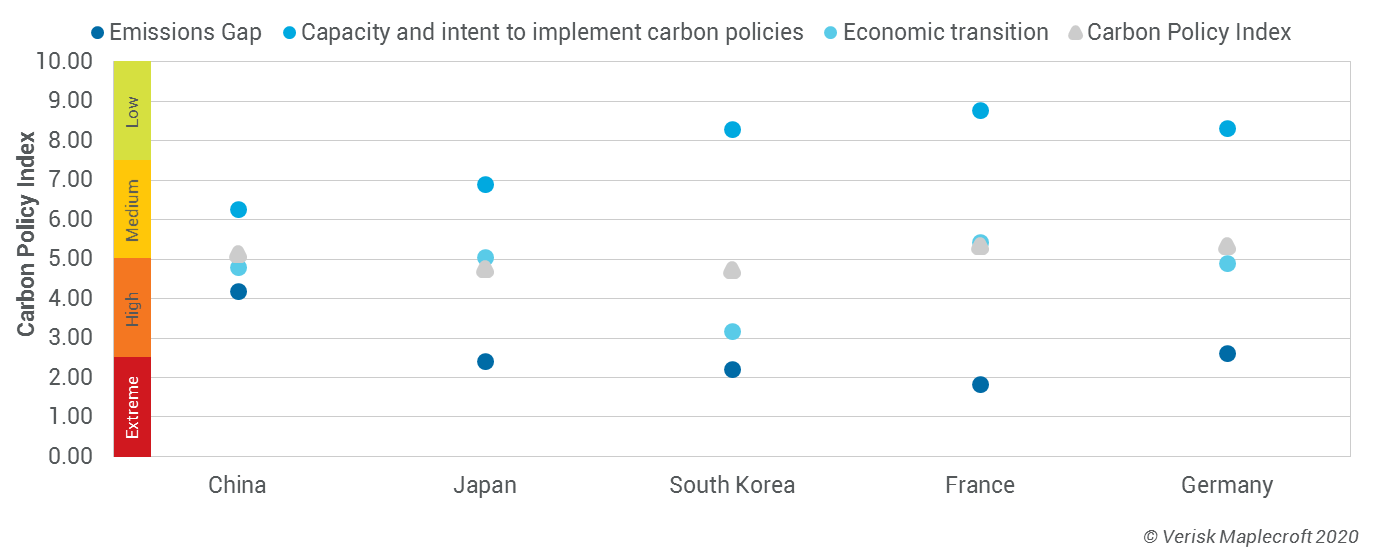

Taken at face value, the pledges put these countries alongside other major economies that have vowed to decarbonise. Indeed, they perform similarly to countries such as France and Germany on our Carbon Policy – Sovereign Index 2020-Q4 (see Figure 1), which assesses the potential for more stringent emissions reduction policies, and the material implications for business.

However, with the targets of 2050 for Japan and South Korea and 2060 for China decades away, none of the current leaders will be in office at that time so there is no risk to Xi Jinping’s, Moon Jae-in’s or Yoshihide Suga’s political legacies if the commitments are oversold at this point.

Meeting these pledges will require consistent policy implementation across multiple governments. This, taken alongside the protracted timelines, a lack of detailed and actionable milestones, large gaps between current and target emission levels, and political and economic uncertainty, mean the path to carbon neutrality in the economic giants of East Asia is likely to be uneven and prone to temporary reversals along the way.

China's long timeline intends to limit economic impact

China has tripled its total emissions over the past 20 years, and now accounts for over a quarter of all global emissions. Under the Paris Agreement, Beijing has committed to peaking emissions before 2030. We expect Beijing to achieve its goal before the end of the decade, owing to a greater share of renewables, improved energy efficiency and other decarbonisation measures.

Post-Paris Agreement, China has set a longer timeframe for reaching zero net emissions than other major economies. Its 2060 target is influenced by several factors, including a desire to limit the economic cost of the energy transition, which is linked to the very prominent role coal still plays in the energy mix. Another factor is a desire to accommodate the lifecycle of new coal-fired powerplants, some of which are set to remain online until the 2050s. In other words, the longer timeline underscores China’s distinctive approach to decarbonisation, which combines increased renewables investment with continued, if diminishing, fossil fuel use.

Find out more about Climate change and environment

The 14th Five-Year Plan, due to be approved in March 2021, will provide a clearer view of the path towards 2060 and just what concrete measures Beijing is betting on. With coal set to remain an important part of the overall energy mix, we expect both a greater emphasis on renewables combined with other decarbonisation options. The latter includes carbon capture and storage (CCS) and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). The plan is also likely to introduce a cap on coal consumption and expansion, emissions targets for cities with heavy industry, and a continued emphasis on gas as a transition fuel.

Japan and South Korea heavy on ambitious goals, light on specifics

Japan’s pledge under Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga marks an acceleration towards decarbonisation, which was lacklustre under the previous administration. The commitment remains light on details though.

The 2050 target is similar to Japan’s other recent decarbonisation pledges on shuttering coal plants and cutting funding for overseas coal projects – both of which are political in nature but have the potential to slash emissions once followed up with concrete measures. We expect these to be unveiled over the next 12 months. Japan’s three-yearly energy policy is undergoing review, and the final version – slated for 2021 – is likely to be aligned with the carbon neutrality pledge.

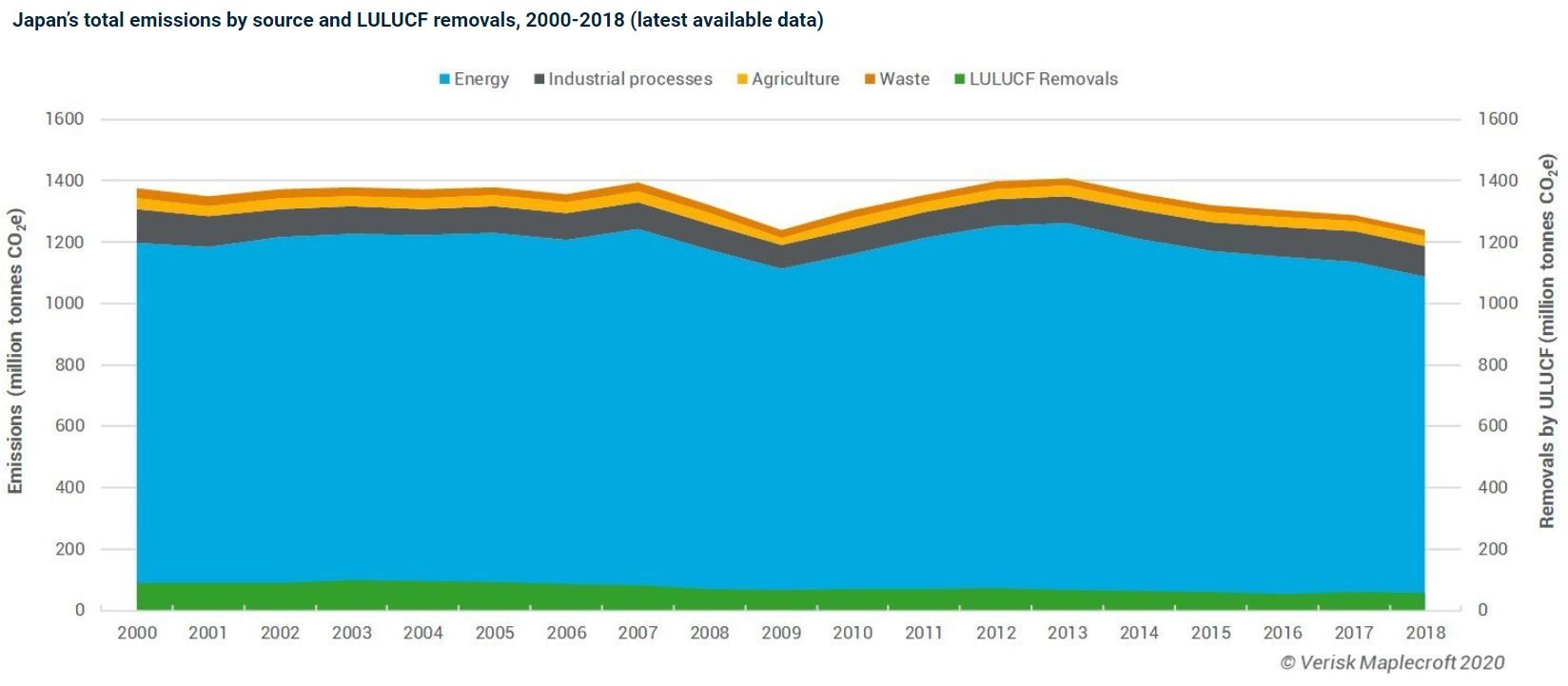

Japan’s total emissions have been on a gradual decline since 2013, when they peaked due to a revival in coal use following the 2011 Fukushima disaster (see Figure 2). However, the country still has a long way to go towards carbon neutrality, and the government has already announced that the power sector will miss its existing 2030 reduction target. Achieving carbon neutrality would require further slashing coal use. The latter still represents a third of Japan’s energy mix and under the current plan is slated to only shrink to a quarter by 2030.

South Korea’s commitments are somewhat more concrete, promising an end to reliance on coal, and building on the country’s USD62 billion Green New Deal announced earlier this year. The latter promises a carbon tax and an end to overseas funding of coal plants. The country currently generates 7% of its total energy from renewables and is aiming to boost this to 20% by 2030; a major step towards eventual carbon neutrality.

But as with Japan, there are some uncertainties about the implementation of the Green New Deal in particular, owing to its ambitious scope combined with relatively limited concrete timelines and targets. Notably, South Korea is yet to set a peak emissions date. While this and other measures are likely forthcoming, future governments will be hamstrung by additional coal capacity, already under construction, which is slated to come online over the next 4-5 years, making quick progress by the middle of the decade difficult.

Two steps forward, one step back?

As in China, economic considerations will play a role in the two northeast Asian neighbours. The funding of overseas coal-fired plants represents a substantial revenue source for South Korean and Japanese banks and companies – which are heavily involved in projects in South and Southeast Asia.

Learn more about our Country Risk Intelligence

In October 2020, 18 EU investors, including major pension and asset management funds, issued a warning over Tokyo and Seoul’s involvement in Vung Ang 2, a coal plant under development in northern Vietnam. Scaling back and eventually eliminating such overseas funding – something that we see as unlikely for at least the next 2-3 years – will be a crucial step towards shoring up confidence in their carbon neutrality pledges.

There is growing consensus in all three countries on the need for decarbonisation, but consistent policies are by no means assured. For example, the conservative opposition in South Korea, which has regained ground, has a realistic shot at the presidency in 2022. Having already promised to scuttle Moon’s green policies in order to shore up economic growth, an election victory for them would effectively stall South Korea’s progress for at least five years.

While not on the immediate horizon – due to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s dominance in Japanese politics, and the likelihood of Xi Jinping remaining in power for the foreseeable future – similar (temporary) reversals are entirely plausible in Japan and China as well. Although they are unlikely to derail the ultimate goal of carbon neutrality, any setbacks can add years to each country’s timeline. This dynamic will likely result in a ‘two steps forward, one step back’ approach to climate policy over the coming decades.