APAC on the front line of Cold War 2.0

by Hugo Brennan,

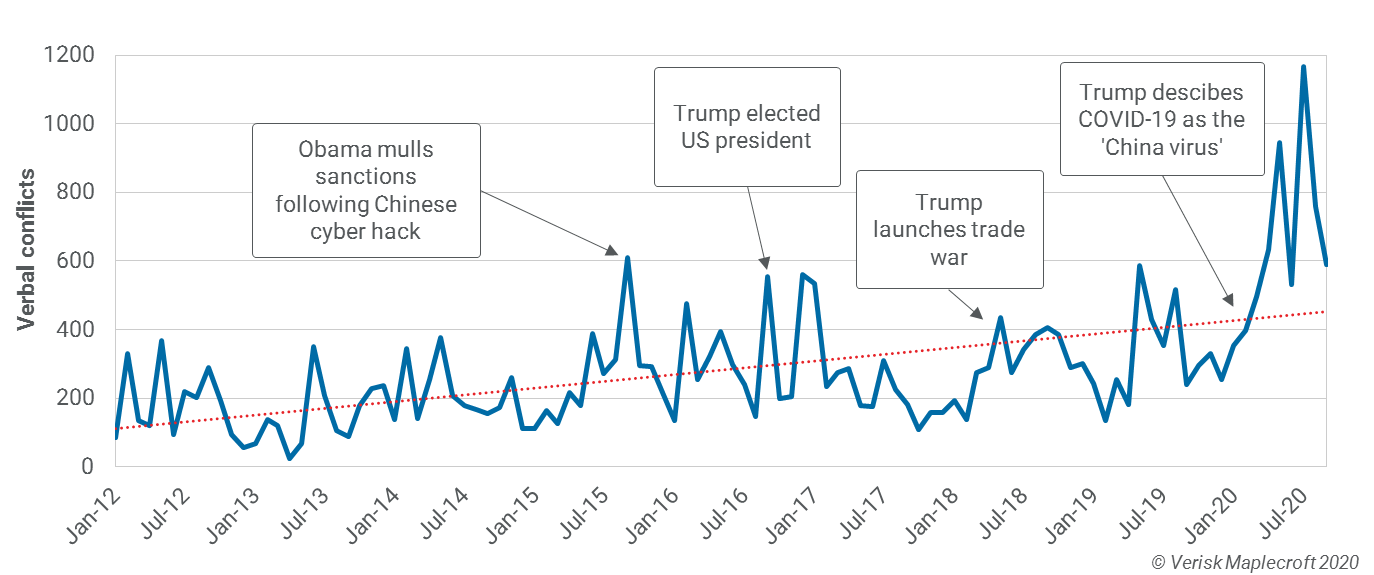

Strategic competition between the US and China has been steadily ratcheting up over the past decade, as indicated by the notable uptick in diplomatic jousting between Washington and Beijing (see chart below). This growing rivalry between the world’s two superpowers – a dynamic many are dubbing a Cold War 2.0 – risks the globe once again becoming bifurcated between opposing geopolitical camps. The Asia-Pacific region is at the heart of this intensifying US-China rivalry, and which way individual states lean will have consequences for companies and investors.

How states across the diverse region are aligning amid growing US-China competition is dependent on a host of factors, including historical bonds, regime type, economic ties, security obligations, personal relationship between leaders, domestic political dynamics and geopolitical self-interest. Taking into consideration this medley of factors, our Asia Risk Insight team have put their heads together to provide a collective assessment of whether individual APAC states are currently ‘aligning with the US’, ‘aligning with China’ or ‘hedging their bets’ (see map below).

The majority of APAC states are sitting on the fence

The first takeaway from this regional analysis is that we judge most states – 16 out of 38 – to be hedging or doing their best to avoid picking a side in this emerging strategic tussle. As the map illustrates, South-East Asia and Oceania are home to the greatest number of non-aligned states, which suggests that these sub-regions will be key theatres for US-China strategic competition. As US-China rivalry intensifies, so does the likelihood of governments across APAC facing the question from Washington and Beijing respectively: are you with us, or against us?

Mongolia is an illustrative example: Ulaanbaatar must maintain cordial ties with Beijing to protect its most important trade relationship, but also values strong relations with Washington as part of its ‘third neighbour strategy’ to offset Mongolia’s dependence on its two giant neighbours, Russia and China. Others states in this camp, such as Papua New Guinea, are keen to try and exploit this geopolitical tussle for their own commercial advantage, by playing one side off against the other to secure much-need investment.

Talk of US decline has been overstated

We judge there to be 14 US-aligned states out of the 38 assessed in this exercise, many of which are closely bound to Washington via its ‘hub and spoke’ network of security alliances. This remains true despite the damage inflicted by four years of President Trump’s America First doctrine, which has eroded trust in allied capitals and stoked perceptions that the US has retreated from its traditional leadership role. We expect a more multilaterally inclined Biden administration to work much more closely with America’s allies in the region.

One notable feature of this cluster of states is that they include countries with a strong claim to ‘major power’ status that have all been on the receiving end of China’s more aggressive foreign policy in recent years, including India, Japan and Australia. On one level, this is because Beijing is focusing its coercive diplomacy on American allies in the region, as a proxy for the broader strategic confrontation with Washington. Australia provides the best example of how China is targeting US-aligned states with economically coercive measure to drive home the price of maintaining close relations with the US. On another, China’s more aggressive foreign policy towards its neighbours is pushing traditionally non-aligned states, such as India and Vietnam, into the US camp.

Find out more about our Country Risk Intelligence

China may be on the rise but lacks strong and reliable allies

While strategic competition in the Asia-Pacific is heating up, and the gap between the dominant and emerging superpowers is narrowing, China still has a long way to go to achieve its ambition of displacing the US as the regional hegemon. In our view, there are just nine China-aligned states out of the 38 we assessed. This cluster includes nuclear-armed Pakistan, Russia and North Korea, although relations with the latter two are complicated by latent mutual distrust and competing strategic prioritises. Many of China’s remaining regional allies are geopolitical minnows such as Nepal, Laos and Cambodia. Another weakness of the China-aligned camp is a lack of formal defence treaties underpinning this patchwork coalition, which stems from Beijing’s historical distrust of formal alliances.

Nowhere is the limit of Beijing’s bid for regional influence starker than the case of Taiwan.

China’s much cherished ‘One Country, Two Systems’ model is in tatters following recent events in Hong Kong and has been roundly rejected in Taipei.

If President Xi wants to achieve his ambition of ‘reunifying’ the self-governing island with the Chinese mainland then a military invasion is now his only realistic option. While Beijing has been flexing its military muscles in the Taiwan Strait, it is under no illusions that such a move would entail a high risk of a cold war with the US quickly escalating into a hot one, with the bulk of the international community likely to back Washington and Taipei. This underpins our assessment that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan remains a remote prospect over the next two years.

Business to be buffeted by geopolitical waves in bifurcated world

Multinational companies and investors will have to navigate increasingly choppy geopolitical waters as the Asia-Pacific drifts into opposing camps.

Trade will be a key battleground. Companies risk the goods and services they provide being targeted by Washington or Beijing, as a means to coerce their home governments into falling into line. For example, Australian wine, barley, cotton and coal exporters are all feeling the pinch as Beijing erects trade barriers designed to punish Canberra – the regional capital most closely allied to the US – amid deteriorating diplomatic relations. The iron ore trade has likely only escaped similarly punitive measures because China’s undiversified import profile makes such actions unfeasible, although this is an equation Beijing is actively seeking to alter.

Find more about our Institutional investor service

An emerging Cold War 2.0 is also likely to entail a proliferation of investment barriers and shifting capital flows within the Asia-Pacific. The sharp downturn in relations between China and Australia can be partly pinned to Canberra’s decision in 2018 to ban Chinese telecoms firms Huawei and ZTE from building its 5G network. The Trump administration has aggressively lobbied its regional allies – from New Delhi to Wellington – to follow suit. And critical infrastructure may yet prove the thin end of the wedge. For instance, the increasing focus on critical mineral supply security in Washington suggests that the ‘geopolitical reliability’ of mineral suppliers and their political masters will rise up the checklist of project investment criteria.

Geopolitical considerations are also one factor driving US allies in the region, such as Japan and Taiwan, to reduce their exposure to China – and Beijing’s penchant for targeting corporates as a means to apply pressure to their home governments – by encouraging firms to repatriate production based in ‘the workshop of the world’ either home or to South-East Asia.

US - China rivalry in the Asia-Pacific is a macrotrend here to stay

The potential for US-China rivalry to cause the Asia-Pacific region to bifurcate into two opposing geopolitical camps is a macrotrend that should be on the radar of all companies and investors with interests in the region. Given that the way individual states lean in this emerging Cold War 2.0 will have consequences for regional trade and investment flows.

Speculation about the imminent decline of the US as the regional hegemon has likely been overstated, despite the damage caused by Trump’s America First doctrine. Yet the battle for power and influence in APAC is only likely to intensify over the coming decade, with South-East Asia and Oceania set to be key theatres for this geostrategic tussle.