Trump’s message on 8 May was unambiguous: the US is withdrawing from the nuclear agreement between Iran and world powers. The American president also sent a clear message that the US will implement the “highest level” of sanctions against Iran.

What happens next is anything but clear. By allowing sanctions waivers to expire, Trump has fired the starting gun on a new Iran policy. Shaping and executing this policy, however, will not be straight forward.

As the US sanctions machine gears up to isolate the Iranian economy, three questions stand out:

- What does the US exit mean for Iran investors?

- How will Iran and the remaining parties to the agreement respond?

- Can the US effectively cut Iranian oil exports?

Definitive answers to these questions will only emerge as the US starts to implement its new Iran policy in the second half of 2018. But early indications strongly suggest that the White House is determined to turn the screws on Iran economically.

There is so far little to suggest that the remaining members of the nuclear agreement can effectively mitigate the impact of the US withdrawal. Still, the lack of international consensus makes the task of isolating the Iranian economy much harder than during the years leading up to the 2015 nuclear agreement.

What does the US exit mean for Iran investors?

There is little doubt that Washington intends to apply maximum pressure to achieve its stated aim of forcing Tehran back to the negotiating table. As a result, the impact on foreign investment in Iran will be immediate.

Overall, the sharp break with the deal is close to a near-worst-case scenarios for most investors. In less than six months, US sanctions that were suspended as part of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) will come back into force. This will effectively expose non-US companies to a raft of US extraterritorial sanctions.

Dozens of companies have signed MoUs since the agreement came into force in January 2016. Most of these have not been turned into finalised agreements due to uncertainty surrounding the Iran deal. With US sanctions coming back into force in the second half of 2018, most of these agreements are likely to fall through.

Trump’s decision to go beyond merely revoking US sanctions waivers is telling. The intention is not just to extricate the US from the deal; the aim is also to apply much greater pressure on the Iranian economy by curbing foreign investment.

The decision to re-designate Iranian entities that were removed from US blacklists as part of the nuclear agreement represents an additional step; sanctions against these entities were revoked rather than suspended.

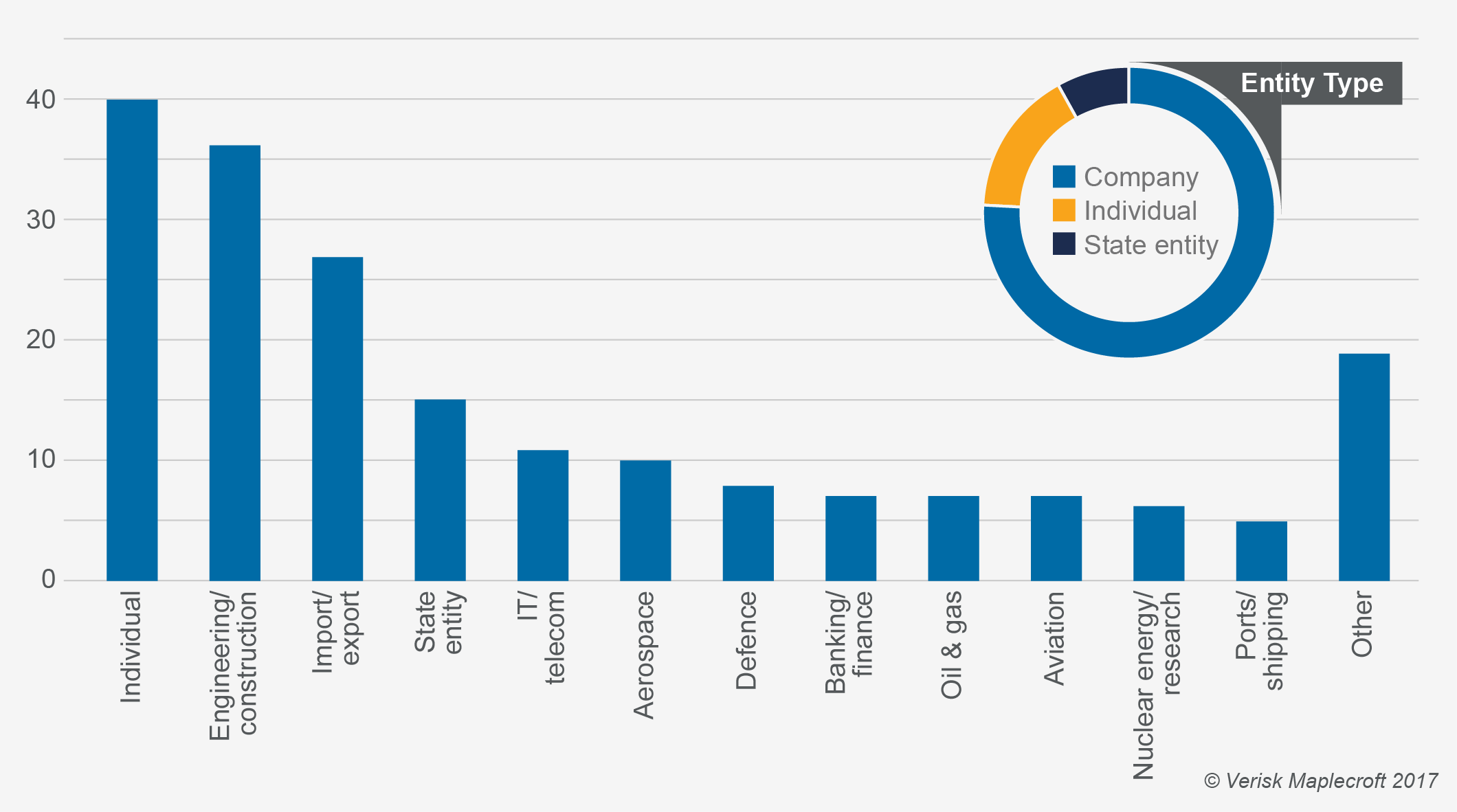

The upshot is that the number of blacklisted entities will increase significantly from November. Currently, as the chart below shows, just over 100 entities are blacklisted by the US. Senior State Department officials have indicated that this number will likely rise to around 700. Even before the US withdrawal from the agreement, the strong presence of blacklisted entities in the Iranian economy has been one of the main barriers for foreign investors.

The distinction between suspended and revoked sanctions is important. If the intention is to apply maximum pressure on the Iranian economy, there is little reason to assume that the US will be forthcoming in issuing waivers for individual countries, companies or projects.

How will Iran and the remaining parties to the agreement respond?

The remaining parties to JCPOA have all stated that they will continue to abide by the agreement. The viability of the deal is in serious doubt, however, especially if the Trump administration follows through on its intention to strangle foreign investment in Iran.

For Iran, the decision whether to remain in or leave the agreement will depend on how successful the US is in isolating the Iranian economy. A struggling economy is precisely what brought Iran to the negotiating table in the first place. At the very least, Iran will want to first see Trump’s resolve tested in practice and if there is still an economic dividend to be reaped.

Russian and Chinese companies will continue to do business in Iran due to their much lower exposure to the US financial system than their European counterparts. Russian and Chinese companies are already active in Iran and both are poised to strengthen their position in the country. Most notably, Zarubezhneft has signed a USD700 million upstream agreement, while China has financed several billion dollars’ worth of projects.

Iran will also want to see if EU efforts to forge an independent position on Iran are successful. Both the UK and France have stated they intend to protect British and French companies from US secondary sanctions. France in particular has taken a hard line, with French finance minister Bruno Le Maire stating that European states should not accept “vassal” status.

Several European states have raised the prospect of deploying legal blocking mechanisms to shield European companies from extraterritorial US sanctions. But the effectiveness of such measures is highly uncertain; at the very least, they would need to be amended to give them real ‘teeth’. The ability of the EU to amend existing blocking mechanisms is also in doubt due to the need for unanimity among all member states.

More importantly, even if appropriate legal mechanisms can be established, European companies themselves may not want to damage relations with the US. Without cast-iron guarantees, most companies will err on the side of caution. No one will want to be the company that puts unproven EU legal mechanisms to the test. Faced with a downside of exclusion from the US financial system and multi-billion-dollar fines, the risks will in most cases outweigh any potential upside.

Can the US effectively cut Iranian oil exports?

Iranian oil exports have more than doubled since the implementation of the JCPOA to around 2.6 million barrels per day (bpd) in April. The Trump administration will likely task the treasury and the state department with bringing this figure down as close to pre-JCPOA levels as possible. In theory, this places up to 1.5 million bpd at risk. But in practice, any removal of Iranian barrels from the international oil market will be significantly lower.

The effectiveness of US-led efforts to cut Iranian oil exports during the height of the international sanctions regime rested on a strong international consensus and high levels of cooperation among key importers of Iranian crude. This time, there is no such consensus.

The 600,000 bpd imported by China will remain well beyond the reach of Washington. US efforts will therefore be directed primarily at the EU, India, Japan and South Korea. Combined, this leaves around 1.55 million bpd that the US can realistically target.

Statements issued by major European states following the US withdrawal from the agreement makes it extremely unlikely that the EU would ban European refineries from importing Iranian oil as it did in 2012. Figures from Eurostat show that the EU imported 550,000 bpd in 2017, with Italy, France and Greece taking the highest volumes. The US may lean on individual EU member states, however, to at least secure an overall reduction in the flow of oil from Iran to Europe.

India is expected to import almost as much Iranian oil as the EU during 2018. But having benefitted from increasingly lucrative discounts this year, India will be reluctant to accommodate US requests to cut Iranian crude oil imports.

South Korea and Japan are both much more likely to fall in line with the US than Indian and most European states. South Korea currently imports just over 300,000 bpd, down from an average of 360,000 bpd in 2017. Japan, meanwhile, imports around 200,000 bpd from Iran. Japan and South Korea’s reliance on the US to meet their security needs gives both states little room for manoeuvre; especially with North Korea currently high on the agenda.

Ultimately, each of the main importers of Iranian oil will have to make a cost-benefit analysis weighing up the economic and political impact of reducing imports of Iranian crude against the risk of damaging relations with the US and any additional costs imposed by Washington.

Uncertainty surrounding other variables make it even more difficult to form an accurate picture of how much Iranian oil the US can take off international markets. Most importantly, the extent of US pressure will have to be tested; and secondly, the willingness of China to increase imports from Iran will be an important factor.

Still, concerted pressure on key allies could remove between 250,000 and 500,000 bpd from international markets. Given the lack of international support for Trump’s decision, anything beyond this looks unlikely without aggressive strong-arm tactics against the biggest importers of Iranian oil.

The decisive factor: political will

Over the coming weeks and months, the impact of the US withdrawal from the JCPOA will be determined by two main factors. Firstly, Washington’s willingness to enforce sanctions; and secondly, the ability of the remaining parties of the agreement to defy or circumvent US sanctions.

So far, there is little reason to doubt the former and a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the latter. Although the EU is exploring options for shielding European companies from US sanctions, such measures are untested.

Even before Trump’s decision to pull the US out of the JCPOA, a complex web of sanctions and legal ambiguity have been sufficient to deter most foreign companies from investing in Iran. As the full spectrum of US Iran sanctions are re-applied, it is beyond any doubt that it will become far more difficult for most foreign companies to do business in Iran.

Curbing Iranian oil exports will be much harder and will require a more active and confrontational approach from Washington to be effective. With Japan and South Korea both vulnerable to US pressure, an overall reduction in Iranian oil exports in 2019 is likely. But it is still too soon to narrow the estimated range which currently spans from tens of thousands bpd to 1 million bpd.