Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to have far-reaching consequences

by Hugo Brennan and James Lockhart Smith and Capucine May and Eileen Gavin and Franca Wolf and Ophelia Coutts,

What has happened?

- On 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine. Russian troops have crossed the Ukrainian border from the north via Belarus, the south via the Russian-held Crimean Peninsula, and the east from Russia itself. Military targets throughout Ukraine, including the capital Kyiv, have also been hit with air and missile strikes.

- President Putin has dubbed the invasion a ‘special military operation’ aimed at the ‘demilitarisation’ and ‘denazification’ of Ukraine. This suggests that his ambitions now go well beyond simply seizing territory in eastern Ukraine and extends instead to regime change in Kyiv.

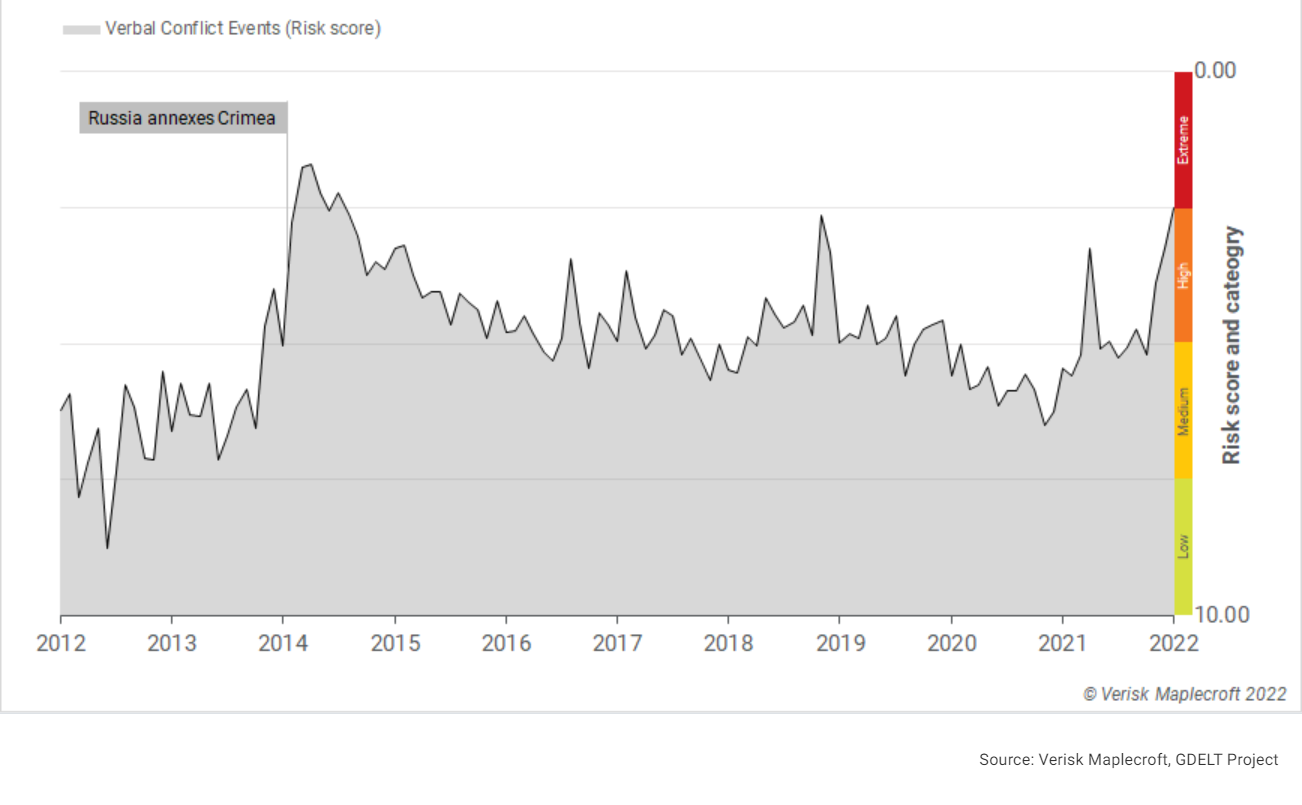

- The dramatic escalation of hostilities is a scenario that we flagged earlier this week and one foretold by the deteriorating performance of the Russia-Ukraine pairing within the Verbal Conflicts indicator of our Interstate Tensions Index since 2021-Q4. Our data shows that the pair’s performance on the indicator was, as of the end of January, worse than at any point since Russia seized the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine in 2014-Q1 (see Figure 1).

- One thing is for certain, the massive escalation of the conflict in Ukraine will have profound consequences for financial and commodity markets, global supply chains and the geopolitical landscape in Europe and beyond.

A fresh round of Western sanctions is on the cards

- We expect further sanctions by the US, EU and other G7 nations, due to be announced today (24 February) or tomorrow (25 February), to be much tougher than previous measures. Western leaders had previously exercised restraint in the hopes of deterring a Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- Amid wider market mayhem, news of the invasion saw Russian bond yields and credit default swaps spike to unprecedented levels. This reflects the risk of a US and EU clampdown on secondary trading in all Russian sovereign debt, further to long-standing bans on participation in primary markets - and, this week, new restrictions on secondary trading in any ruble and non-ruble bonds issued from March onwards. Any wider ban, on the table in Washington since last year, will generate significant losses for emerging market investors.

- As of today, there is little reason for Western policymakers to keep this deterrent arrow in their quiver any longer. Equally, they have little to gain from it in the immediate term, and more potent tools for disrupting the Russian economy are at their disposal.

- The EU has already outlined the sanctions it is drawing up: export controls, asset freezes, and the exclusion of Russian banks from the continent’s financial markets (even though a SWIFT payments block is reportedly unlikely for now). We expect Washington to coordinate closely with Brussels today and place a similar emphasis on banks and export controls. Critically, the US also has the option of fully designating the Central Bank, as it did earlier this week with the VEB development bank.

Fortress Russia is far from invulnerable to Western retaliation

- The conventional wisdom is that Russia is well protected from punitive sanctions after several years of bulking up its foreign reserves, especially yuan and gold, and reducing its dependence on external debt. Furthermore, even when painful, sanctions have historically been ineffective at deterring Russian aggression.

- However, as of mid-2021, around 49% of Russia's Central Bank reserves were held in dollars and euros; and the same proportion is located in the USA, Canada, European capitals and in Japan. That means that any full US designation of Russia's Central Bank, and wider EU-US banking curbs, could have a sweeping impact on both the ruble and the country’s financial stability, commerce, and ultimately on household savings.

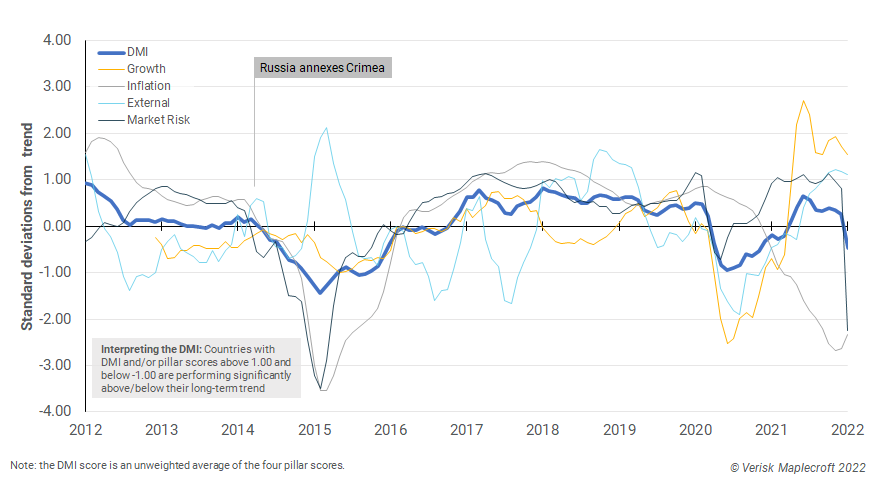

- As shown in Figure 2, Russia’s performance in Verisk Maplecroft’s Dynamic Macroeconomic Index (DMI) shows slowing economic growth since 2021-Q3 as hiking inflation continues to exacerbate poor living conditions. We expect Russia’s DMI score to decline further as sanctions are imposed. Ultimately, however, the Kremlin will prioritise its immediate ambitions in Ukraine over economic growth and the living standards of the populace.

EU refugee flows to increase human rights risks, boost anti-immigration parties

- A direct intervention by NATO in Ukraine remains a remote possibility, and it is also unlikely that Russia will launch an attack on a NATO member in the coming days. Poland and the Baltic states have nonetheless invoked NATO’s Article 4, which triggers the alliance to consult when a member state feels threatened. The four countries will certainly ask for further NATO deployments in the region.

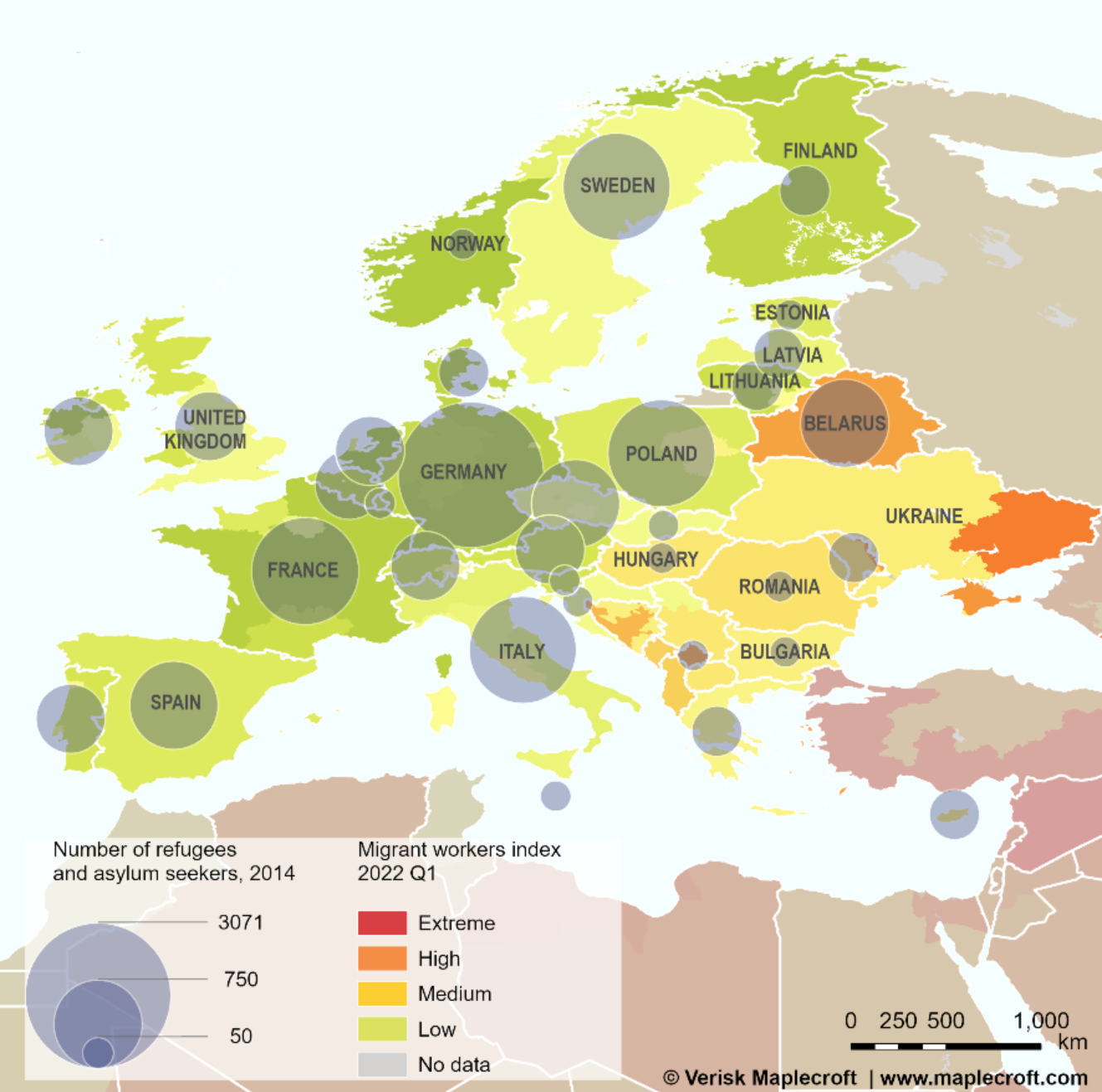

- Preparations are underway across the EU to accommodate the wave of Ukrainian refugees expected to seek asylum in the bloc. Patterns observed following the annexation of Crimea suggest that France, Germany, Italy and countries neighbouring Ukraine – particularly Poland – will bear the brunt of the influx. Most of these countries score as medium risk on our Migrant Workers Index, which suggests a refugee crisis will increase human rights risks for corporates operating there (see Figure 3).

- The prospect of a refugee crisis will be a boon for right-wing anti-immigration parties throughout the EU. Ahead of elections in April 2022, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán has already woven the scenario of a migrant crisis into his political campaign. Likewise, France’s Eric Zemmour’s ‘Immigration Zero’ campaign will gain traction, potentially pushing him ahead of Marine Le Pen in the opinion polls.

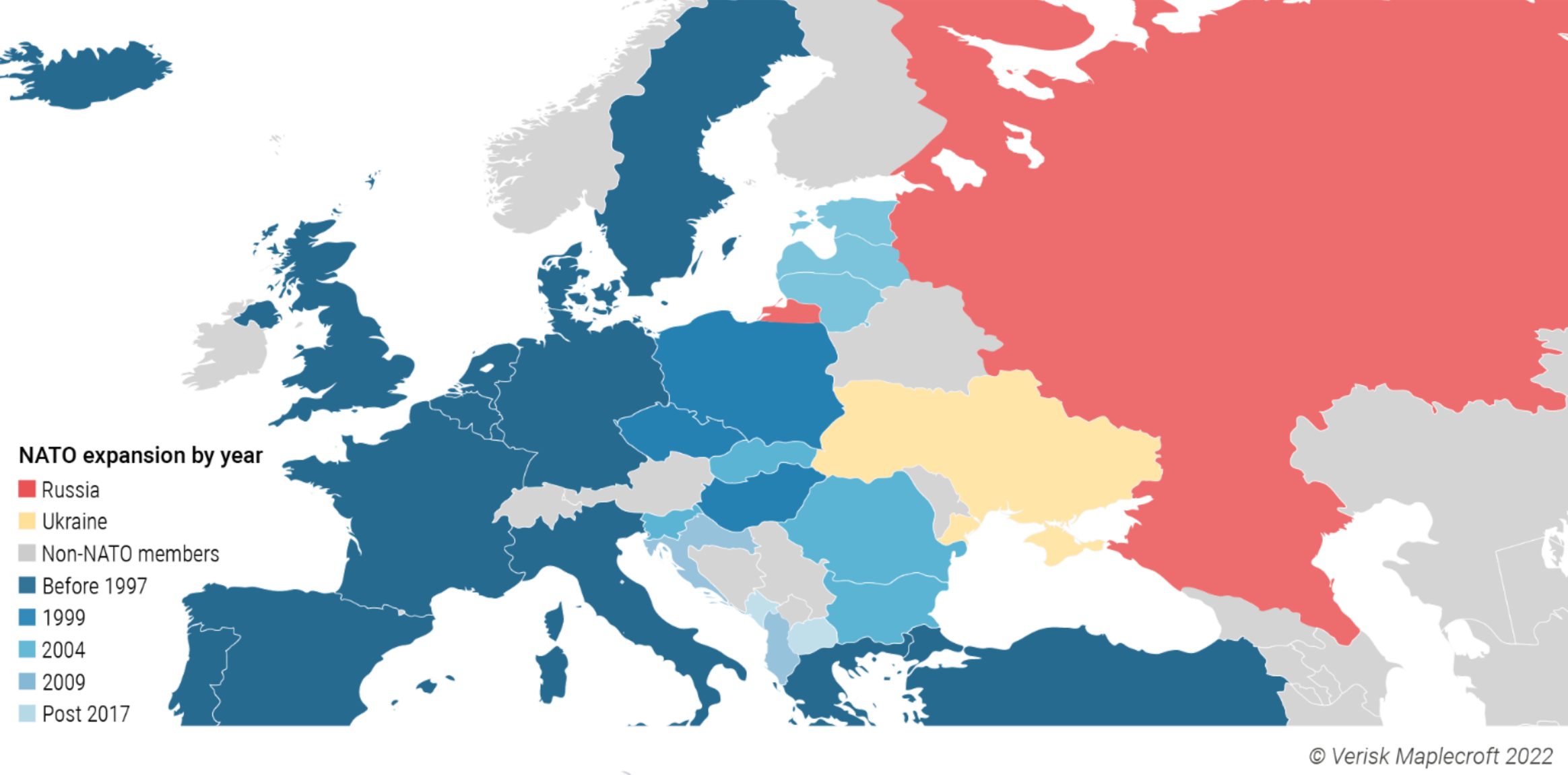

Invasion set to bolster NATO and heighten concerns over Taiwan

- The UN Security Council has once again demonstrated that it’s not fit for purpose in this new era of great power competition between the democratic West and authoritarian East. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will only serve to underscore the importance of NATO to European peace and security and revive debates in non-member European states about joining the alliance. This is ironic, given that Russia has cited NATO expansion as one of the key drivers behind the decision to invade Ukraine (see Figure 4).

- More broadly, China will be closely watching to see how the West responds to Russian aggression, with an eye on its goal of ‘reunifying’ self-governing Taiwan with the mainland. Russia’s actions will also give voice to those advocating for the QUAD – a loose coalition between America, Australia, India and Japan – to become a formal military alliance aimed at containing China, another authoritarian ‘great power’ seeking to carve out a sphere of influence in its near-abroad.

A major setback to Emerging Market recovery prospects

- The initial shock – and the global market response – was entirely predictable, with an immediate flight to safety in the shape of the USD/US treasuries and gold.

- The immediate risk is to food and energy price inflation. EM sovereigns, led by Turkey, Egypt and Lebanon, are highly dependent on the supply of wheat from Russia and Ukraine and the crisis raises food insecurity fears in MENA. Indeed, NATO member Turkey is exposed on multiple fronts, from the economic to the geopolitical.

- Key signposts of a wider contagion will be EM currencies, such as the Polish zloty, along with the usual EM risk bellwethers including the Turkish lira, the South African rand and the Brazilian real.

- High oil prices are a positive for Saudi Arabia/MENA and EM oil stocks as a whole, but a negative for Eastern Europe and Asia given high pass-through to the Asian industrial sector, with India particularly exposed.

- Markets had already discounted a Fed move in March, with the ECB also very unlikely to start tapering now. The outlook will be for further rate hikes in highly inflation-exposed EMs. Indebted sovereigns in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia face a much more complex outlook, with stagflation a real threat.

Breakdown of energy trade unlikely, but invasion adds impetus to EU’s energy transition

- The energy trade between Russia and the EU is one of mutual dependency, which reduces the likelihood that Russia will halt gas exports or that European sanctions will directly target gas imports in the short term. After all, 44% of the EU’s gas imports came from Russia in 2020 and almost 40% of Russia’s 2019 federal budget was financed by oil and gas.

- Moscow has weaponised energy exports before and has recently limited gas supply to put pressure on prices. However, European gas imports continued throughout the Crimea crisis and shut off the pipelines to Europe would undermine Moscow’s aim to be seen as a reliable energy partner. As Moscow looks eastwards for new markets, it wants to maintain its reputation as a reliable partner.

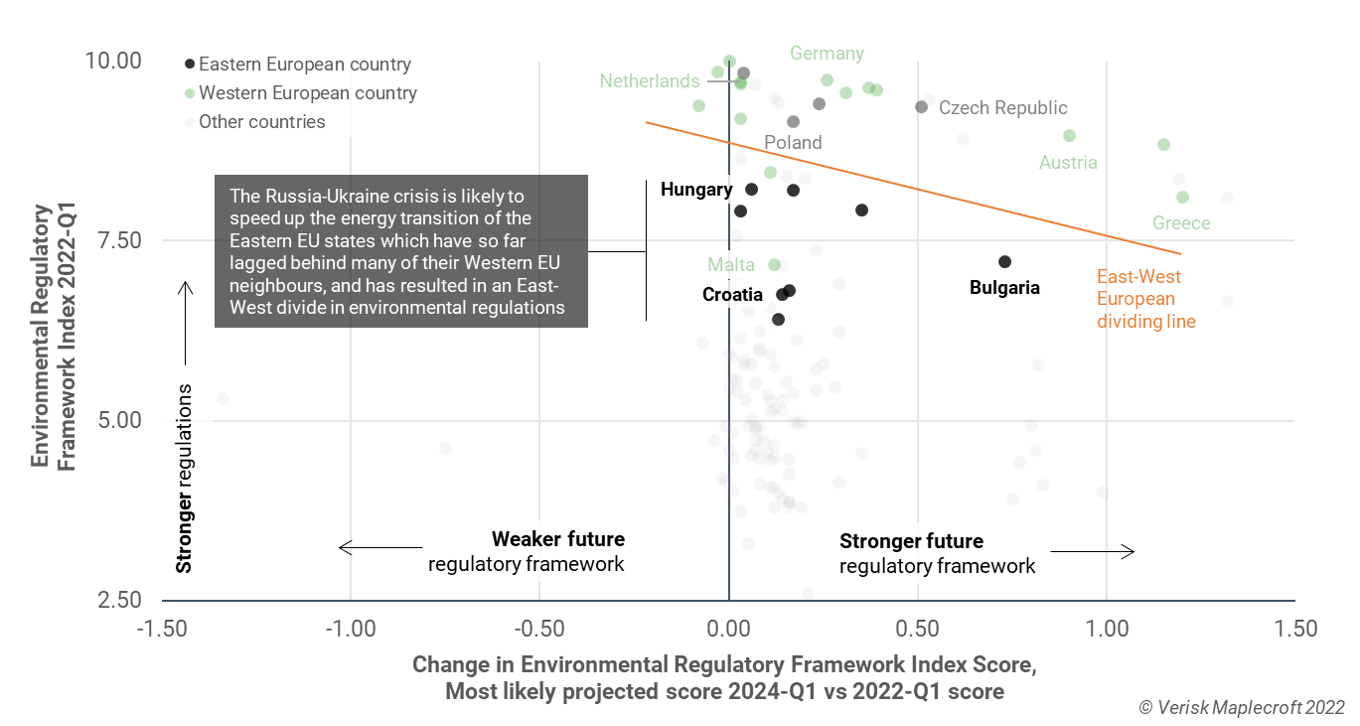

- Beyond the short term, Russia’s invasion will serve as an impetus for Europe to move away from Russian gas, if only to look to Nordic states, North Africa or LNG for new sources. Moreover, in an effort to more closely align themselves with the EU, the current crisis is likely to speed up the energy transition of Eastern EU states which have so far lagged behind their Western neighbours (see Figure 5).

Conflict likely to disrupt commodity exports

- Ukraine’s top exports – notably corn, wheat, seed oil and iron ore – are at severe risk of disruption as the conflict threatens maritime, air and land-based transport routes.

- For one, military attacks are likely to damage transport infrastructure, including roads, railways, ports and airports. The key port cities of Odessa, a main exporter of grain, and Mariupol, through which a fifth of Ukraine’s ferrous metals are exported, have been targets of Russian attacks. The Black Sea and Sea of Azov also remain at high risk of a naval blockade.

- Ukraine is one of the most important exporters of grains globally and any disruption to this trade would be felt well beyond its borders. The resulting spike in global cereal prices would put further strain on countries across the Middle East and North Africa – the region most reliant on Ukrainian cereal exports and one that already struggles with food insecurity.

- Ukraine supplies nearly 70% of the world’s neon gas used in the production of semiconductors. While tech companies have been quick to reassure clients that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will not disrupt the supply of semiconductor, chip manufacturers will be scrambling to find new suppliers of this niche raw material.